Mini Review

Incidence of symptom-driven Coronary Angiographic procedures post-drug-eluting Balloon treatment of Coronary Artery drug-eluting stent in-stent Restenosis-does it matter?

Victor Voon1*, Dikshaini Gumani1, Calvin Craig2, Ciara Cahill1, Khalid Mustafa1, Terry Hennessy1, Samer Arnous1 and Thomas Kiernan1

1Cardiology Department, University Hospital Limerick, Dooradoyle, Limerick, Ireland

2Graduate Entry Medical School, University Hospital Limerick, Limerick, Ireland

*Address for Correspondence: Dr. Victor Voon, Specialist Registrar in Cardiology, Cardiology Department, University Hospital Limerick, Ireland, Tel: 00 353 61 585694, Fax: 00 353 61 485122; Email: [email protected]

Dates: Submitted: 16 June 2017; Approved: 28 June 2017; Published: 29 June 2017

How to cite this article: Voon V, Gumani D, Craig C, Cahill C, Mustafa K, et al. Incidence of symptom-driven Coronary Angiographic procedures post-drug-eluting Balloon treatment of Coronary Artery drug-eluting stent in-stent Restenosis-does it matter? J Cardiol Cardiovasc Med. 2017; 2: 035-041.

DOI: 10.29328/journal.jccm.1001011

Copyright License: © 2017 Voon V. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

ABSTRACT

Objectives: The clinical impact of drug-eluting balloon (DEB) coronary intervention for drug-eluting in-stent restenosis (DES-ISR) is not fully known. To further evaluate this impact, we aimed to describe the incidence of symptom-driven coronary angiography (SDCA), an under-reported but potentially informative outcome metric in this cohort of patients. Methods: We retrospectively identified all patients (n=28) who had DEB-treated DES-ISR at University Hospital Limerick in between 2013-2015 and evaluated the incidence of subsequent SDCA as the primary endpoint. Data were expressed as mean ± SD and %. Results: Baseline demographics demonstrate a mean age 63±9 years with 61% of DEB-treated DES-ISR presenting with acute coronary syndrome. Mean number of ISR per patient and number of DEB per lesion was 1.2±0.6 lesions and 1.2±0.6 balloons, respectively. The incidence of SDCA was 54% after mean follow-up duration of 179±241 days. 67.8% of patients had follow-up data beyond 12 months. Within the first year of follow-up, the incidence of SDCA with and without target lesion revascularization (TLR) was 11% and 36% respectively. Among patients with SDCA without TLR, 30% had an acute coronary syndrome not requiring percutaneous coronary intervention. Conclusions: A high incidence of SDCA was observed, particularly within the first 12 months after DEB-treated DES-ISR. This under-reported metric may represent a cohort at higher cardiovascular risk but requires further confirmation in larger studies.

INTRODUCTION

The clinical impact of drug-eluting balloon (DEB) treatment as a novel percutaneous coronary intervention strategy for drug-eluting stent (DES) in-stent restenosis (ISR) is a subject of ongoing interest [1]. Current knowledge of better DES safety profiles have resulted in guidelines recommending DES by default regardless of clinical conditions and lesion subsets [2].

Nevertheless, the persistent and non-negligible problem of DES-ISR remains and little is known regarding optimal management of this entity [3]. Indeed, in recent times, the use of DEB to treat DES-ISR, has become an increasingly attractive non-metal-based option over stent-based strategies. In this effort of defining the impact of DEB, many studies have reported on target vessel revascularization (TLR) rates in DEB-treated DES-ISR [4-9].

However, a neglected but potentially informative outcome measure of DEB-treated DES-ISR relates to the requirement of further symptom-driven coronary angiographic procedures (SDCA). Such poorly reported outcomes are not insignificant due to accompanying non-negligible coronary angiographic procedural complication. Furthermore, these presentations may shed further understanding on risk stratifying patient phenotypes and more accurately define the impact of DEB in DES-ISR. Therefore, we aimed to report on the incidence of SDCA of patients after DEB-treated DES-ISR.

METHODS

This observational study was approved by the ethics committee of University Hospital Limerick, and conformed to the principles of the Helsinski Declaration. We retrospectively identified all patients treated with DEB for ISR, including DES-ISR from 2013-2015 within University Hospital Limerick database. Subsequently, baseline demographics, clinical presentations, medication, procedural and angiographic data as well as follow-up events were collected from the local database and medical records. Patterns of ISR were documented as previously described [10]. Paclitaxel-based Pantera Lux (Biotronik) DEB was used in all patients and post-DEB angiographic success was defined as achievement of TIMI 3 flow and final residual stenosis <30%. Dual antiplatelet therapy was recommended for at least 1 year post-procedure.

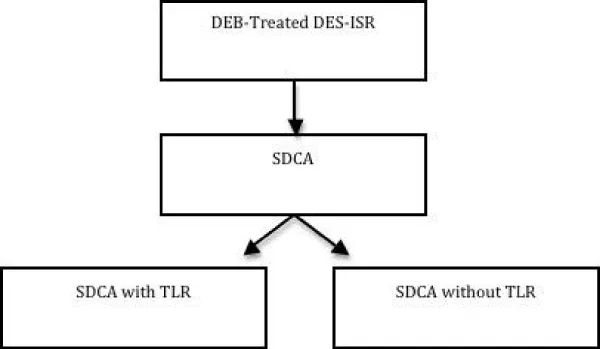

The primary endpoint was incidence of SDCA performed. SDCA was defined as coronary angiography performed on the basis of persistent symptoms reported by the patient and after clinical assessment by independent cardiologists. Symptoms were defined as angina or angina-equivalent with/without exertion. Within this cohort, patients with and without target lesion revascularization (TLR) were identified. Patients presenting with acute coronary syndromes (ACS) without need for PCI were also observed within the SDCA without TLR group (Figure 1). TLR was defined as any repeat percutaneous or surgical coronary intervention due to ISR (diameter ≥ 70%) in the DEB-treated segment with associated symptoms and signs of ischemia. Secondary endpoints were major adverse cardiac event (MACE), defined as all cause of death, heart failure, stroke, ACS requiring PCI and target vessel revascularization (TVR). TVR was defined as any repeat percutaneous or surgical coronary intervention of any segment of the treated vessel.

STATISTICS

Data are presented as mean SD or frequencies (and percentages) for continuous normal or nominal/categorical variables, respectively. Analyses were carried out using SPSS version 18 statistical software (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois).

RESULTS

A total of 28 patients treated with DEB were identified. Baseline demographics and medication profiles are described in table 1 and 2, with 61% acute coronary syndrome clinical presentations due to ISR requiring DEB treatment. Pre-DEB treatment, all patients were on aspirin and 75% on a second anti-platelet drug. All patients had DES-ISR. Mean number of ISR per patient was 1.2±0.6 lesions (Table 3). 69% had focal ISR lesions (Table 4). Baseline procedural profiles are shown in table 5. Mean number of DEB per lesion was 1.2±0.6 balloons. Post-DEB, angiographic success was achieved in all patients. 33% of patients had second anti-platelet switched to an alternative anti-platelet drug.

| Table 1: Baseline demographic profiles of total patient cohort. | |

| Variables | All patients N=28 |

| Age, years | 62.6 ± 8.9 |

| Gender, Male/ Female ratio | 26 / 2 |

| Hypertension (%) | 17 (61%) |

| Diabetes (%) | 4 (10%) |

| Prior MI | 12 (43%) |

| Prior CABG | 8 (29%) |

| CKD-HD (%) | 4 (14%) |

| PAD (%) | 2 (7%) |

| CVA (%) | 1 (4%) |

| EF, % | 48 ± 8 |

| Clinical presentation: SA UA NSTEMI STEMI |

11 (39%) 11 (39%) 3 (11%) 3 (11%) |

| MI, myocardial infarction; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; CKD-HD, chronic kidney disease requiring hemodialysis; PAD, peripheral arterial disease; CVA, cerebrovascular accident; SA, stable angina; UA, unstable angina; NSTEMI, Non-ST elevation myocardial infarction; STEMI, ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Data are expressed as mean±SD and % | |

| Table 2: Baseline medication profiles of total patient cohort. | |

| Variables | All patients N=28 |

| Aspirin | 28 (100%) |

| Ticagrelor | 2 (7%) |

| Clopidogrel | 18 (64%) |

| Prasugrel | 1 (4%) |

| Anticoagulant | 1 (4%) |

| ACEi/ARB | 20 (71%) |

| BB | 19 (68%) |

| MRA | 0% |

| Diuretics | 3 (11%) |

| Statin | 26 (93%) |

| ACEi, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor; angiotensin receptor blocker;BB, beta-blockers; MRA, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist. Data are expressed as % | |

| Table 3: Baseline angiographic profiles of total patient cohort. | |

| Variables | All patients N=28 |

| Total number of diseased arteries >50% stenosis: 1 2 3 4 |

7 (25%) 13 (47%) 6 (2%) 2 (7%) |

| Restenosed index stent: DES BMS Unknown |

28 (100%) 0 0 |

| Number of lesions (ie ISR) per patient : 1 2 3 4 |

24 3 0 1 |

| Number of target lesions (ie ISR) treated by DEB: 1 2 ≥3 |

27 1 0 |

| Number of target vessels treated with DEB 1 ≥2 |

28 0 |

| ISR, in-stent restenosis; DES, drug-eluting stent; BMS, bare-metal stent; DEB, drug-eluting balloon. Data are expressed as % | |

| Table 4: Baseline in-stent restenosis lesion profiles of total patient cohort. | |

| Variables | All patients N=28 |

| Target vessels (ie ISR): LM LAD/Diagonal LCx/OM RCA IM VG |

1 (3%) 8 (29%) 7 (25%) 10 (36%) 0 2 (7%) |

| Length of lesion, mm | 7.7 ± 4.4 |

| Pattern of ISR: Focal margin Focal body Multifocal Diffuse Proliferative Occlusive |

4 (14%) 15 (55%) 1 (3%) 7 (25%) 0 1 (3%) |

| Bifurcation lesion | 0 |

| RCA ostial lesion | 1 (3%) |

| Stent fracture | 0 |

| LM, left main coronary artery; LAD, left anterior descending coronary artery; LCx, left circumflex coronary artery; OM, obtuse marginal coronary artery; RCA, right coronary artery; IM, intermediate coronary artery; VG, vein graft; ISR, in-stent restenosis. Data are expressed as mean ± SD and % | |

| Table 5: Baseline procedural profiles of total patient cohort. | |

| Variables | All patients N=28 |

| Radial approach | 20 (71%) |

| Pre-dilatation | 25 (89%) |

| Pre-dilation balloon diameter, mm | 3.1 ± 0.5 |

| Pre-dilation balloon length, mm | 14.0 ± 2.7 |

| DEB diameter, mm | 3.3 ± 0.5 |

| DEB length, mm | 14.9 ± 3.6 |

| Number of DEB per lesion | 1.2 ± 0.6 |

| Post-dilatation | 8 (29%) |

| Post-dilation balloon diameter, mm | 3.6 ± 0.7 |

| Post-dilation balloon length, mm | 13.6 ± 3.5 |

| Intracoronary nitrate | 9 (32%) |

| Intracoronary GP2B3A inhibitor | 1 (4%) |

| Angiographic success | 100% |

| POST-DEB | |

| Aspirin | 100% |

| Clopidogrel | 16 (57%) |

| Ticagrelor | 12 (43%) |

| 2nd antiplatelet switch | 33% |

| DEB, drug eluting balloon; GP2B3A inhibitor, glycoprotein 2B3A inhibitor; DAPT, dual anti-platelet therapy. Data are expressed as mean ± SD and % | |

| Table 6: Follow-up outcomes of total patient cohort. | |

| Variables | All patients N=28 |

| Primary endpoint | |

| Incidence of SDCA, (%) | 16 (57%) |

| Mean follow-up duration to SDCA, days | 179 ± 241 |

| Incidence of SDCA without TLR, (%) | 12 (43%) |

| Mean follow-up duration to SDCA without TLR, days | 141 ± 212 |

| Incidence of SCDA without TLR within first year, (%) | 10 (36%) |

| Mean follow-up duration to SDCA without TLR within the first year, days | 59 ± 61 |

| Incidence of SDCA with TLR, (%) | 4 (14%) |

| Mean follow-up duration to SDCA with TLR, days | 307 ± 283 |

| Incidence of SDCA with TLR within first year, (%) | 3 (11%) |

| Mean follow-up duration to SDCA with TLR within first year, days | 134 ± 141 |

| Secondary endpoint | |

| All cause of death, (%) | 0 (0) |

| Stroke, (%) | 0 (0) |

| Heart failure, (%) | 0 (0) |

| ACS requiring PCI, (%) | 0 (0) |

| TVR, (%) | 0 (0) |

| SDCA, symptom-driven coronary angiography; TLR, target lesion revascularization; ACS, acute coronary syndrome; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; ISR, in-stent restenosis; TVR, target vessel revascularization. Data are expressed as mean ± SD and % | |

Mean follow-up duration for all patients was 534±316 days. During this period, the primary endpoint of incidence of SDCA was 54% after mean follow-up duration of 179±241 days (Table 6). 67.8% of patients had follow-up data beyond 12 months. Within the first year of follow-up, incidence of SDCA with and without TLR was 11% and 36%, respectively. 23% (3 out of 13) of patients requiring SDCA within the first year, had TLR performed. Sub-analysis showed that the minority of patients had diffuse pattern of DES-ISR in both SDCA with TLR (n=1) and SDCA without TLR (n=2) groups. The other patients with diffuse DES-ISR at baseline (n=5) had no further SDCA/TLR. In addition, 80% (8 out of 10 patients) requiring SDCA without TLR and 67% (2 out of 3 patients) requiring SDCA with TLR were already on dual anti-platelet therapy prior to DEB for DES-ISR at baseline. Interestingly, 30% (3 out of 10) of patients in SDCA without TLR group experience ACS not requiring PCI and all these occurred within the first year of follow-up. During the total follow-up period, 3 patients had non-symptom driven coronary angiographic procedures performed but none required further PCI. No deaths, stroke, heart failure, target vessel revascularization nor ACS requiring PCI were observed during the total follow-up period.

In this single centre registry, we have for the first time, reported on a high incidence of symptom-driven coronary angiography in patients treated with DEB for DES-ISR. Over half (54%) of the patients within 2 years and nearly half (46%) of patients within 1 year of follow-up, required SDCA. This represents real-life data compared to studies to date, which have often reported on scheduled follow-up coronary angiographic procedures regardless of presence of symptoms. Furthermore, recent observations demonstrate lack of correlation between current metrics by scheduled routine coronary angiography with TLR and/or lesion quantification, and the prediction of major adverse cardiovascular events [4-6,8]. Scheduling serial transradial coronary angiography increases the risk of radial/ulnar artery occlusion, a rare complication, but that may limit vascular access for these higher risk patients who will likely require further PCI. In our baseline cohort, 29% of patients required DEB treatment via femoral access due to poor radial/ulnar access, thus increasing peri-procedural bleeding risk. Therefore, if possible and appropriate, complementary non-invasive stress imaging should be considered to risk stratify such symptomatic patients.

However, it may be inevitable that certain patients require SDCA with TLR as demonstrated in our study at an incidence of 11% within the first year. This figure represents nearly a third of all SDCA within the first year and is comparable to previous studies estimating TLR incidence of 2.9% at 6 months [11] and 22.1% at 12 months [7] in patients with DEB-treated DES-ISR. This may not be surprising as a potential at-risk cohort as 61% of patients with DES-ISR at baseline presented with an acute coronary syndrome in our study. Interestingly, we only observed 10% of diabetics in our cohort compared to previous studies reporting incidence 33-42.9% [4,6,7]. Despite that, diabetes has not been shown to significantly influence the impact of DEB in DES-ISR [6].

Furthermore, MACE incidence was 0% in our cohort during the total follow-up duration. This may be explained in part by specific re-classification of ACS not requiring PCI/TLR within the SDCA without TLR group. Indeed, no ACS requiring PCI nor TVR were observed throughout follow-up. We regard this to be a more informative definition of follow-up events in our patient cohort. The incidence of MACE in several major studies have been reported as follows: MACE 7.7% (including myocardial infarction (MI) 5.1%, TLR 2.6%) at 9 months in the GARO registry [4]; MACE 16.8% (including 0% MI, 15.3% TLR) in PEPCAD-DES study [6]; and MACE 23.5% (which included MI 2.8%, TLR 22.1%) at 12 months in the ISAR-DESIRE 3 trial [7]. However, the generalized description of such outcomes may result in lack of useful inferences relating to ISR. Thus, SDCA may itself be a more clinically meaningful marker of a higher risk cohort but this requires clarification in larger studies.

Indeed, patients with SDCA may represent a subgroup lacking optimization of medical therapy, a subgroup at risk of coronary artery spasm [12], a subgroup with microvascular disease that may be at higher risk of requiring repeat TLR and/or a subgroup of patients with a lower threshold for ischemia. Post-DEB for DES-ISR, patients requiring SDCA without TLR may be at higher risk of coronary disease progression. Symptoms may be a reflection of ongoing microvascular disease downstream which is stimulated by vasoactive and proinflammatory markers released by DES-ISR site beyond the effects of homogenous local anti-proliferative drug delivery by DEB. Such changes may in turn contribute to the propagation of neointimal negative remodeling, thus accelerating coronary disease. This may be explained by our data demonstrating that 30% of patients with SDCA without TLR experienced acute coronary syndrome during the first year of follow-up.

Finally, diffuse-type ISR was recently suggested to cause early DES-ISR and several studies have reported on incidence over 40% of such lesions in DES-ISR [1,4,6]. However, the impact of such lesions after DEB for DES-ISR remains unknown. Post-DEB, diffuse-type DES-ISR at baseline did not appear to predict TLR as demonstrated in our study. In fact, the majority of patients having such angiographic lesions did not have further SDCA nor MACE during the follow-up period. Therefore, this supports the potential of SDCA being more useful clinical barometer in larger studies to quantify and predict risk of disease progression in DEB-treated DES-ISR.

LIMITATIONS

We acknowledge several limitations to this study. First, this was a retrospective, observational, single-centre study with small sample size, which lacked a comparator group. However, as aforementioned, it also represents real-life data that can be extrapolated into daily clinical practice. Therefore, despite being hypothesis generating, such results should be cautiously applied. Second, we were unable to obtain data of several variables such as time course between DES implantation and ISR, generation-type of DES used, previous DES size, mechanical factors (eg. stent under-expansion), use of intracoronary imaging post-DEB, and non-invasive stress imaging prior to SCDA. These parameters would be informative in future observational studies performed. Third, we acknowledge the possibility of coronary vasospasm is a contributor towards symptoms reported and lack provocation testing in this regard.

CONCLUSION

A high incidence of symptom-driven coronary angiography was observed, particularly within the first 12 months after DEB-treated DES-ISR. This under-reported metric may represent a cohort at higher cardiovascular risk but requires further confirmation in larger studies.

REFERENCES

- Dangas GD, Claessen BE, Caixeta A, Sanidas EA, Mintz GS, et al. In-stent restenosis in the drug-eluting stent era. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010; 56: 1897-1907. Ref.: https://goo.gl/i2K8Ux

- Kolh P, Windecker S. ESC/EACTS myocardial revascularization guidelines 2014. Eur Heart J. 2014; 35: 3235-3236. Ref.: https://goo.gl/oMwtxJ

- Cassese S, Byrne RA, Schulz S, Hoppman P, Kreutzer J, et al. Prognostic role of restenosis in 10 004 patients undergoing routine control angiography after coronary stenting. Eur Heart J. 2015; 36: 94-99. Ref.: https://goo.gl/kA6ux6

- Auffret V, Berland J, Barragan P, Waliszewski M, Bonello L, et al. Treatment of drug-eluting stents in-stent restenosis with paclitaxel-coated balloon angioplasty: Insights from the French "real-world" prospective GARO Registry. Int J Cardiol. 2016; 203: 690-696. Ref.: https://goo.gl/bYnMgT

- Habara S, Kadota K, Shimada T, Ohya M, Amano H, et al. Late Restenosis After Paclitaxel-Coated Balloon Angioplasty Occurs in Patients With Drug-Eluting Stent Restenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015; 66: 14-22. Ref.: https://goo.gl/nfTbAW

- Rittger H, Brachmann J, Sinha AM, Waliszewski M, Ohlow M. A randomized, multicenter, single-blinded trial comparing paclitaxel-coated balloon angioplasty with plain balloon angioplasty in drug-eluting stent restenosis: the PEPCAD-DES study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012; 59: 1377-1382. Ref.: https://goo.gl/PPmyrE

- Byrne RA, Neumann FJ, Mehilli J, Pinieck S, Wolff Bet, et al. Paclitaxel-eluting balloons, paclitaxel-eluting stents, and balloon angioplasty in patients with restenosis after implantation of a drug-eluting stent (ISAR-DESIRE 3): a randomised, open-label trial. Lancet. 2013; 381: 461-467. Ref.: https://goo.gl/rL6SRN

- Xu B, Gao R, Wang J, Yang Y1, Chen S, et al. A prospective, multicenter, randomized trial of paclitaxel-coated balloon versus paclitaxel-eluting stent for the treatment of drug-eluting stent in-stent restenosis: results from the PEPCAD China ISR trial. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2014; 7: 204-211. Ref.: https://goo.gl/uKAZDD

- Lee JM, Park J, Kang J, Jeon KH, Jung JH, et al. Comparison among drug-eluting balloon, drug-eluting stent, and plain balloon angioplasty for the treatment of in-stent restenosis: a network meta-analysis of 11 randomized, controlled trials. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2015; 8: 382-394. Ref.: https://goo.gl/aYJr8o

- Mehran R, Dangas G, Abizaid AS, Mintz GS, Lansky AJ, et al. Angiographic patterns of in-stent restenosis: classification and implications for long-term outcome. Circulation. 1999; 100: 1872-1878. Ref.: https://goo.gl/q6UMhf

- Habara S, Iwabuchi M, Inoue N, Nakamura S, Asano R, et al. A multicenter randomized comparison of paclitaxel-coated balloon catheter with conventional balloon angioplasty in patients with bare-metal stent restenosis and drug-eluting stent restenosis. Am Heart J. 2013; 166: 527-533. Ref.: https://goo.gl/tJcVJE

- Ito S, Nakasuka K, Morimoto K, Inomata M, Yoshida T, et al. Angiographic and clinical characteristics of patients with acetylcholine-induced coronary vasospasm on follow-up coronary angiography following drug-eluting stent implantation. J Invasive Cardiol. 2011; 23: 57-64. Ref.: https://goo.gl/3B6mf8