More Information

Submitted: January 04, 2023 | Approved: January 17, 2023 | Published: January 18, 2023

How to cite this article: Habib M, Elhout S. Outcomes of intervention treatment for concurrent cardio-cerebral infarction: a case series and meta-analysis. J Cardiol Cardiovasc Med. 2023; 8: 004-011.

DOI: 10.29328/journal.jccm.1001147

Copyright License: © 2023 Habib M, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Keywords: Acute stroke; Myocardial infarction; Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI); Mechanical thrombectomy (MTE); Modified ranking scale (mRS)

Outcomes of intervention treatment for concurrent cardio-cerebral infarction: a case series and meta-analysis

Mohammed Habib1* and Somaya Elhout2

1Head of Cardiology Department, Al-Shifa Hospital, Gaza, Palestine

2Cardiology Department, Al-Shifa Hospital, Gaza, Palestine

*Address for Correspondence: Mohammed Habib, MD, PhD, Head of Cardiology Department, Al-Shifa Hospital, Gaza, Palestine, Email: [email protected]

Background: The concurrent occurrence of acute ischemic stroke and acute myocardial infarction is an extremely rare emergency condition that can be lethal. The causes, prognosis and optimal treatment in these cases are still unclear.

Methods: We conducted the literature review and 2 additional cases at Al-Shifa Hospital, we analyzed clinical presentations, risk factors, type of myocardial infarction, site of stroke, modified ranking scale and treatment options. We compare the mortality rate among patients with combination intervention treatment (both percutaneous coronary intervention for coronary arteries and mechanical thrombectomy for cerebral vessels) and medical treatment at the hospital and 90 days after stroke.

Results: In addition to our cases, we identified 94 cases of concurrent cardio-cerebral infarction from case reports and series with a mean age of 62.5 ± 12.6 years. Female 36 patients (38.3%), male 58 patients (61.7%). Only 21 (22.3%) were treated with combination intervention treatment.

The mortality rate at hospital discharge was (33.3%) and the mortality rate at 90 days was (49.2%). In patients with the combination intervention treatment group: the hospital mortality rate was 13.3% and the 90-day mortality rate was: 23.5% compared with the mortality rate in medical treatment (23.5% at the hospital and 59.5% at 90 days (p value 0.038 and 0.012 respectively)

Conclusion: Concurrent cardio-cerebral infarction prognosis is very poor, about a third of patients died before discharge and half of the patients died 90 days after stroke. Despite only one-quarter of patients being treated by combination intervention treatment, this treatment modality significantly reduces the mortality rate compared to medical treatment.

Concurrent occurrence of Acute Ischemic Stroke (AIS) and Acute Myocardial Infarction (AMI) are very rare medical emergency conditions and leading causes of morbidity and mortality worldwide [1]. Both conditions have a narrow therapeutic time window and have a high risk of mortality. The use of intravenous thrombolytics for acute myocardial infarction (AMI) increases the risk of intracranial hemorrhagic [2,3] and the use of a thrombolytic in acute ischemic stroke (AIS) increases the risk of cardiac wall rupture in the setting of early hours of AMI [4].

The association between cerebrovascular disease and coronary artery disease was reported in the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Event (GRACE) trial suggested the incidence of intra-hospital stroke was 0.9% in patients presenting with acute coronary syndrome and the incidence was much higher in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction than the non-ST elevation myocardial infarction [5].

The definition of concurrent cardio-cerebral infarction according to Alshifa Hospital classification [6], Concurrent cardio-cerebral infarction syndrome can be diagnosed by the presence of simultaneous onset of a focal neurological deficit, indicating acute stroke and chest pain with evidence of elevation of cardiac enzymes and electrocardiogram changes to confirm a myocardial infarction. The prevalence rate of concurrent CCI was between 0.009% to 0.29% [7-9].

The present review examines that we analyzed clinical presentations, risk factors, type of myocardial infarction, site of stroke, the modified ranking scale at discharge and at 90 days after discharge hemorrhage, and treatment options.

Case 1

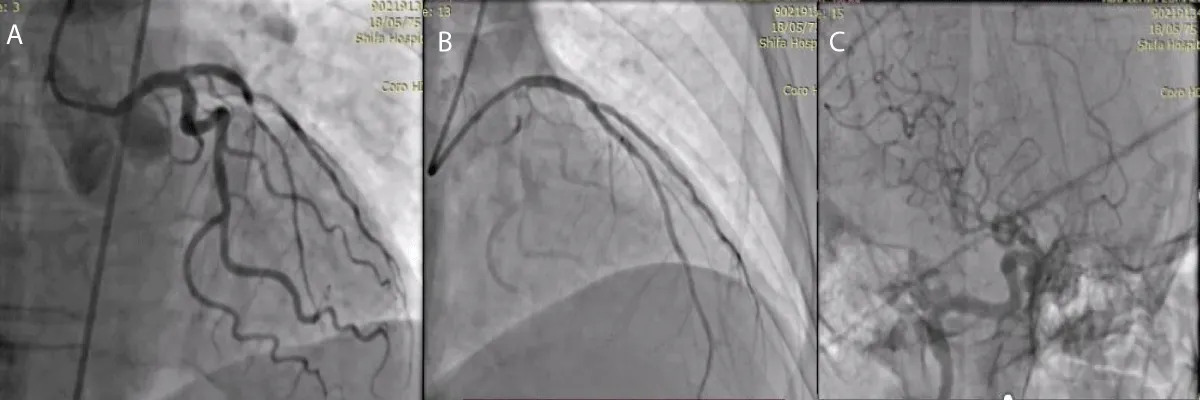

A 67-year-old male patient wasn’t known case of any chronic illness, and presented with chest tightness radiating to both shoulders associated with sweating and nausea for 2 hours, on examination: Patient was conscious, oriented, sweaty, not in respiratory distress and his blood pressure: was 150 / 90 mmHg, Temperature: 37 °C, Heart rate: 80 bpm O2 saturation: 99%, Electrocardiography (ECG) was done at the Emergency department which was showing ST-segment Elevation in V1 - V6 leads with reciprocal changes in inferior leads II, III, AVF. Aspirin 300 mg, clopidegrel 600 mg and morphine 3 mg were given then according to AL-Shifa Hospital protocol, patient was transferred to cardiac catheterization department for primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (PCI), then coronary angiography showed total occlusion of proximal left anterior descending artery (LAD), other vessels were normal, So coronary wire passed freely in LAD and resolute integrity stent 3 x 18 mm (drug eluting stent) was deployed successfully in proximal LAD, during that patient developed sudden onset of left upper limb and left lower limb weakness, National institute of health scale score (NIHS) score 8, So cerebral angiography was done and it was showing TICI Flow III with residual thrombus in MCA (Figure 1), by microcatheter in right middle cerebral artery, intra-arterial alteplase 8 mg was given, then weakness completely was resolved after 10 min with no residual neurological deficit, after that patient was transferred to coronary care unit for 2 days and discharged with good general condition and mRS (0), then he was maintained on aspirin 100 mg daily, clopidogrel 75 mg daily, atorvastatin 80 mg daily and bisoprolol 5 mg daily. Echocardiography: suggested apical hypokinesia with 1.2 x 1.1 mm thrombus, impaired left ventricular ejection fraction: 36%. Follow-up after 3 months was done and the patient had mRS 0.

Figure 1: A- coronary angiography, total occlusion of proximal LAD, B- after stent deployment in proximal LAD, C-cerebral angiography, TICI Flow III with residual thrombus in MCA.

Case 2

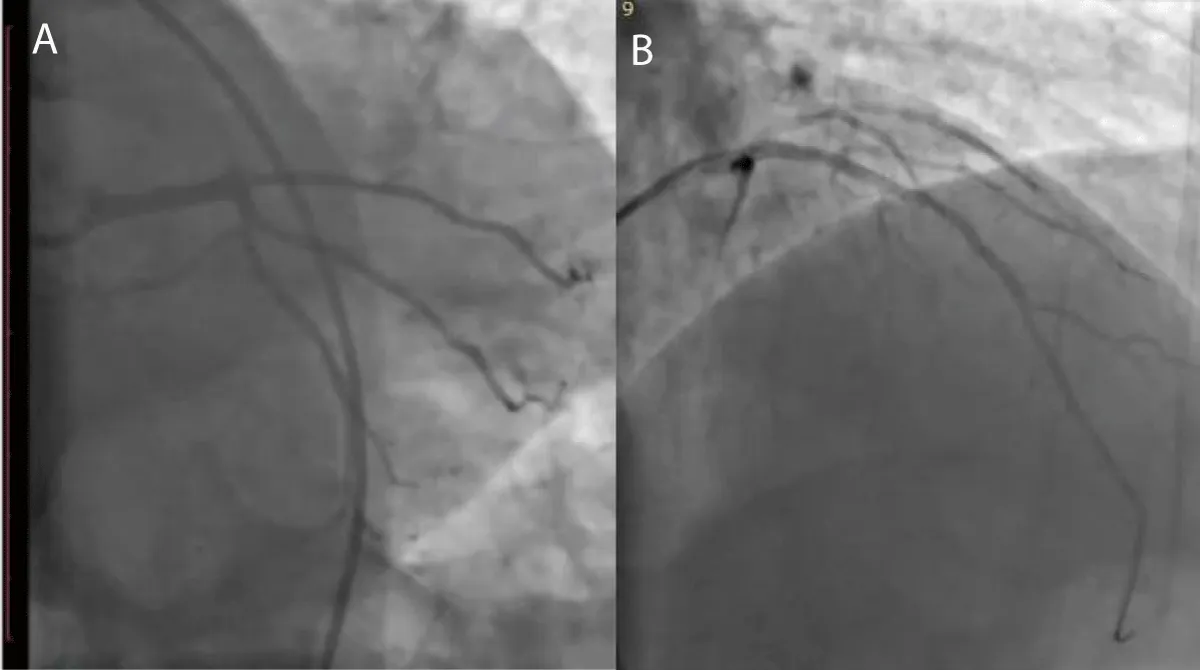

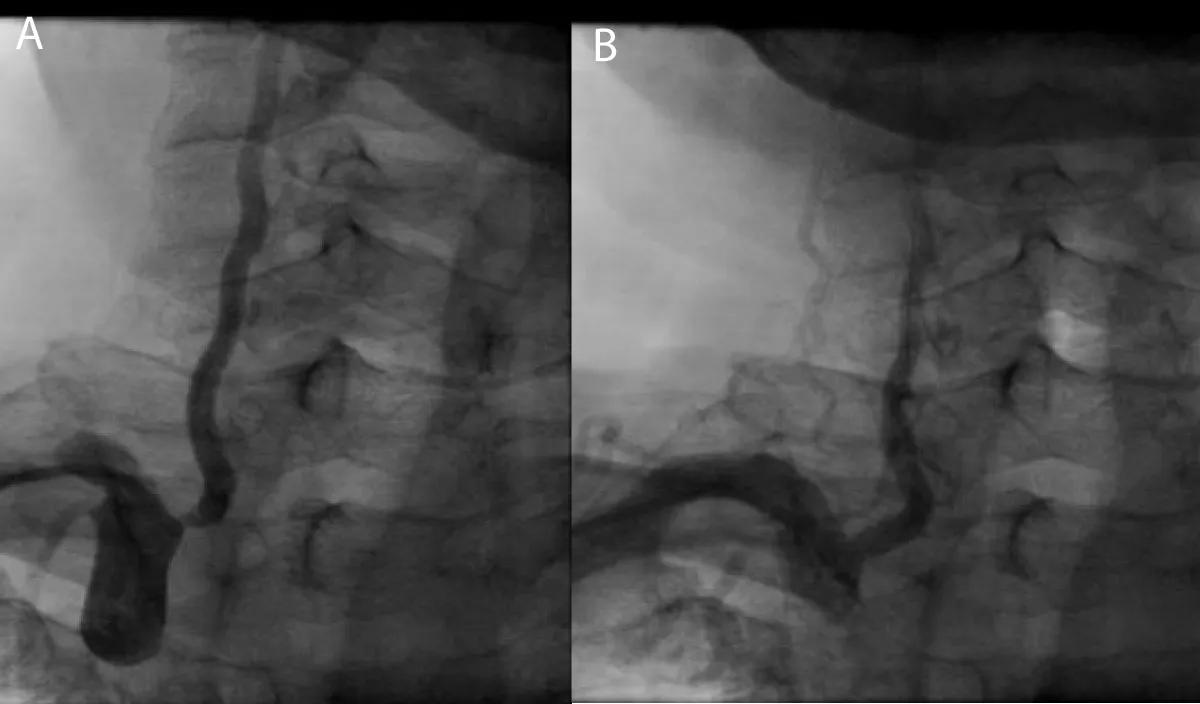

A 63-year-old male patient, previously healthy, hypertensive, diabetic and heavy smoker presented with acute burning chest pain radiating to both shoulders, which was associated with sweating and vomiting for 1 hour, but during hospitalization in the emergency room, he developed sudden onset of altered level of consciousness, dysarthria, nystagmus with National Institute of Health Scale Score (NIHS) score 12, after discussing the case we planned to do coronary and cerebral angiography. On examination the patient looks in pain, sweaty and tachypneic, and their blood pressure: was 75/40 mmHg, Electrocardiography was done and it revealed ST segment elevation in the anterior leads with ST-segment depression in I, II, AVF after that he received 300 mg of aspirin, 300 mg clopidogrel and norepinephrine 3 mcg/kg/min intravenous was started and urgently he was transferred to cardiac catheterization department for primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (PCI). During coronary angiography, it showed total occlusion of the proximal left anterior descending artery, stenting was done successfully by using resolute integrity 2.75 x 22 mm drug-eluting stent (Figure 2), then cerebral angiography showed normal anterior and middle cerebral circulation, but there was severe right vertebral artery stenosis, so angioplasty to vertebral artery was planned and it was done successfully (Figure 3), echocardiography was done and it showed reduced left ventricular Ejection Fraction about 30% - 35%, but no left ventricular thrombus was detected, then the patient was followed for 3 days at the hospital and he was discharged on Dual antiplatelet and he had mRS (0) with regular follow up at the outpatient clinic for 3 months, he had the good general condition and functioning well without any neurological deficit mRS (0).

Figure 2: A-coronary angiography shows proximal LAD total occlusion, B-after stent implantation in ostial LAD.

Figure 3: A- Cerebral angiography shows severe right vertebral artery stenosis, B- After successful angioplasty for vertebral artery.

Study design and patient selection

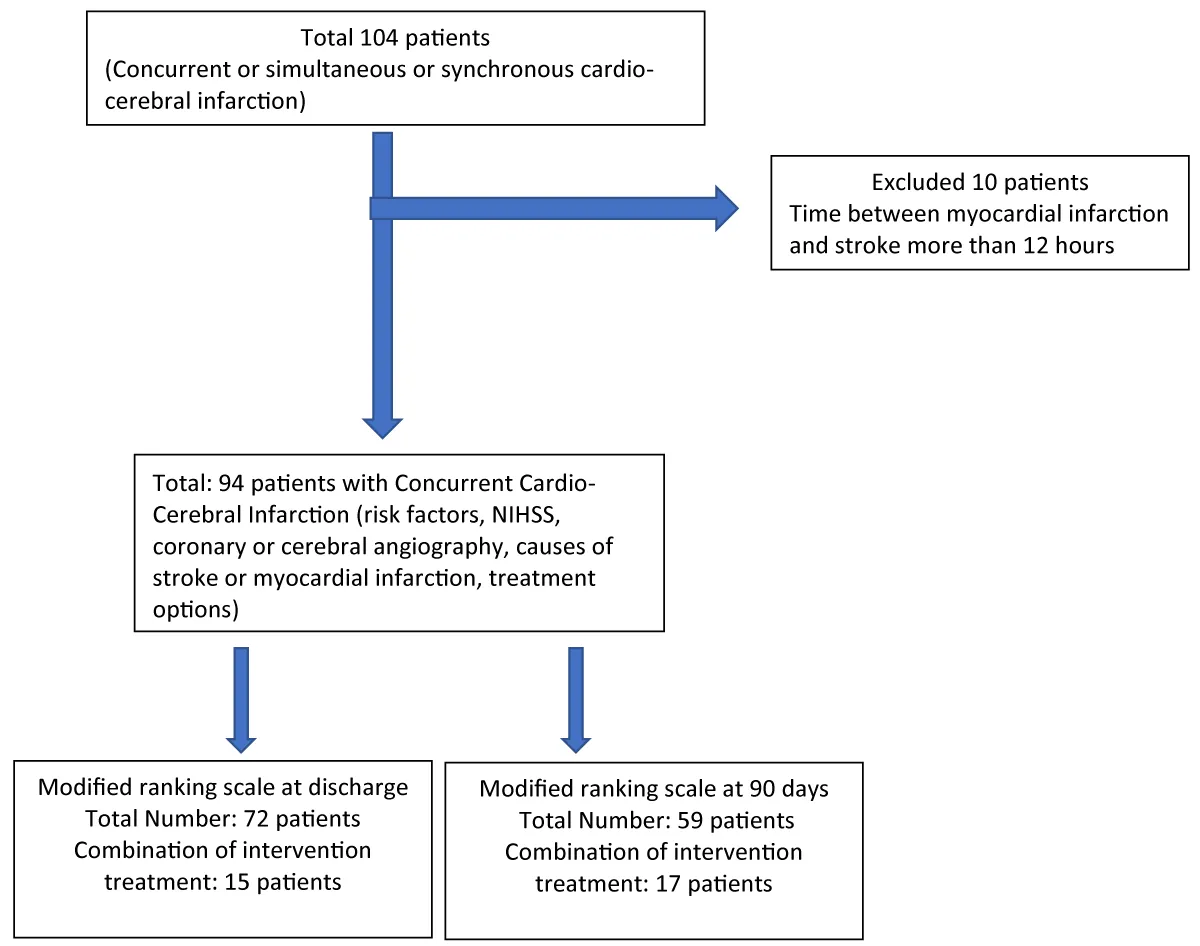

In this metanalysis, we screened retrospective a comprehensive analysis of five databases, PubMed, Embase, Scopus, Research Gate and Google Scholar on concurrent or simulations and synchronous Cardio-cerebral infarction to locate all case reports or case series done on this topic. Based on the literature review and 2 additional cases at Al-Shifa Hospital, Figure 4.

Figure 4: Flowchart summarizing case report selection.

Inclusion criteria: We analyzed all the cases of concurrent cardio cerebral infarction (The occurrence of acute ischemic stroke and acute myocardial infarction either at the same time or one after the other within 12 hours).

Exclusion criteria: The occurrence of acute ischemic stroke and acute myocardial infarction one after the other more than 12 hours.

Definitions of concurrent cardio-cerebral infarction

The occurrence of acute ischemic stroke (onset of a focal neurological deficit) and acute myocardial infarction (elevation of cardiac enzymes plus ischemic symptoms and/or ECG changes and/or loss of viable myocardium on noninvasive test and/or coronary artery thrombus on angiography) either at the same time or one after the other within 12 hours.

Data collection

The following variables were collected: age and sex ,vascular risk factors (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, atrial fibrillation, history of coronary heart disease, dyslipidemia, smoking and previous stroke), stroke location (anterior vs posterior circulation; in anterior circulation strokes, right or left), stroke severity at admission evaluated by the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS), first symptoms of cardio cerebral infarction (chest pain: Myocardial infarction or neurological deficit: acute ischemic stroke or synchronous symptoms chest pain and neurological deficit at same time) stroke etiology, presence of large vessel occlusion, myocardial infarction electrocardiographic subtype (ST elevation myocardial infarction: STEMI vs Non ST elevation myocardial infarction: NSTEMI), in STEMI Cases localization: anterior, inferior and lateral, coronary angiography findings and infarcted related artery (culprit lesion), AMI treatment namely percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and AIS treatment by mechanical thrombectomy (MTE). Antithrombotic medication. Outcomes according to the modified Rankin Scale (mRS) in-hospital and the 3-months were registered. (Supplementary material).

Combination intervention treatment

Combination of treatment by: AMI treatment namely Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (PCI) for coronary arteries and AIS treatment by Mechanical Thrombectomy (MTE) for cerebral arteries.

Statistical analysis

Baseline variables Continuous data are reported as means ± SD. Categorical data are presented as absolute values and percentages. NIHSS, hospitalization time and time between acute ischemic stroke and acute myocardial infarction were calculated as median (lower-upper value). Using the x2, Fisher calculates the mortality rate between females and males, and between patients treated with combination treatment with PCI plus MTE and medical treatment. Significance level was set at p value < 0.05. Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS Statistics, Version 23.0.

Patient characteristics

A total of 104 cases were collected from the literature; 10 cases were excluded due to the time between stroke and myocardial infarction being more than 12 hours. A total of 94 cases were analyzed, with a mean age of 62.5 ± 12.6 years. Female 36 patients (38.3%), male 58 patients (61.7%). The time between stroke and myocardial infarction is 0.5 hours (0 - 12 hours). The most common risk factors of concurrent CCI were hypertension (46.8%) followed by diabetes mellitus and atrial fibrillation. The median NIHSS was 15 (range: 1 - 30) and the most type of myocardial infarction type was anterior ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (38.3%), the most culprit lesion in coronary arteries was the left anterior descending artery (28.7%), the most common culprit artery in the brain was left middle cerebral artery (30.9%). Cardiac and neurological investigations were performed on 94 patients by both ECG and computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging Table 1.

| Table 1: Baseline characterizes in patients with cardio-cerebral infarction. | |

| Risk factors: | |

| Hypertension | 44 (46.8%) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 26 (27.7%) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 19 (20.2%) |

| Previous stroke | 11 (11.7%) |

| Smoker | 16 (17%) |

| History of Coronary artery disease | 11(11.7) |

| Dyslipidemia | 19 (20.2%) |

| Stroke severity NIHSS (median) | 15(1-30) |

| The type of myocardial infarction: | |

| Anterior ST-segment elevation | 36 (38.3%) |

| Inferior wall St segment elevation | 26 (27.7%) |

| Non-ST elevation myocardial infarction | 20 (21.3%) |

| Inferior ST elevation and Right ventricle infarction | 5 (5.3%) |

| High Lateral ST elevation Myocardial infarction | 2 (2.1%) |

| Non-Reported | 5 (5.3%) |

| Infarcted related artery (IRA) | |

| Left anterior descending artery | 27 (28.7%) |

| Right coronary artery | 22 (23.4%) |

| Left circumflex artery | 4 (4.3%) |

| No significant stenosis | 3 (3.2) |

| Non-reported | 38 (40.4%) |

| Culprit stenosis in cranial arteries | |

| Middle cerebral artery | Right 18 (19.1%), Left 29 (30.9%) |

| Basilar artery | 10 (10.6%) |

| Internal carotid artery | Right 7(7.4%), Left 5 (5.3%) |

| Non-reported | 17 (18.1%) |

| No stenosis | 4 (4.3%) |

| Anterior cerebral artery | 1 (1.1%) |

| Left common carotid artery | 2 (2.1%) |

| Right vertebral artery | 1(1.1%) |

Treatments in concurrent cardio-cerebral infarction patients

Medication: Alteplase forty-one patients were treated with intravenous t-PA (43.6%), for antiplatelet and anticoagulation 69(73%) patients were reported and 25(27%) patients were not reported, Dual antiplatelet 27(39%) patients, single antiplatelet 7(10%) patients, a combination of dual antiplatelet and anticoagulation 26(37.7%) patients (5 NOAC and 21 warfarin), a combination of single antiplatelet and anticoagulation 5(7%) patients (3 warfarin and 2 NOAC), anticoagulation alone 4 (6%) patients (1 NOAC and 3 warfarin).

Interventions procedures: Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) was used to treat 29 patients (30.8%): PCI with a balloon only 9 (9.6%), PCI with aspiration only 1(3.2%), PCI with Bare metal stent 3(3.2%), PCI with Drug-eluting stent 16(17%). Treated via Mechanical thrombectomy of cerebral vessels in 24 patients (25.5%). Only 21(22.3%) were treated in combination with both PCI and Mechanical thrombectomy of cerebral vessels.

Causes of cardio cerebral infarction

The most common cause of cardio cerebral infarction was a cardiogenic shock. Hypotension (37.2%), heart failure (37.2%), then atrial fibrillation (25.5%) and left ventricle thrombus (21.3%) Table 2.

| Table 2: Causes of cardio cerebral infarction. | |

| Cardiogenic shock/hypotension | 35 (37.2%) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 24 (25.5%) |

| Left ventricle thrombus | 20 (21.3%) |

| Atherosclerosis | 32 (34%) |

| COVID-19 infection | 6(6.4%) |

| Heart failure | 35 (37.2%) |

| Aortic dissection | 4 (4.3%) |

| Malignancy | 2 (2.1%) |

| Patent foramen ovale | 1 (1.1) |

Causes of death

We identified confirmed causes of death in only 23 patients. The most causes of the patient were cardiac causes 18 (78%) such as ventricle tachyarrhythmias, cardiac Tamponade, aortic dissection, ventricle septal rupture, or sudden death. Noncardiac causes 5(22%): sepsis, infections and multi-organ failure.

Outcomes

We calculated the outcome according to the modified ranking scale which is 0 - 2: mild disability, 3 - 5: moderate to severe disability and 6: death. The modified Rankin Score (mRS) was measured in 72 patients at the hospital and in 59 patients at 90 days.

The mortality rate was 33.3% at hospital discharge measured from 72(76.6%) patients and at 90 days the mortality rate was (49.2%) measured from 59(62.8%) patients (Table 3).

| Table 3: Modified ranking scale (mRS) outcomes at hospital discharge and at 90 days after cardio-cerebral infarction: | |

| The modified ranking scale at hospital discharge (number: 72 patients) | |

| mRS 0 - 2 (mild disability) | 32 (44.4%) |

| mRS 3 - 5 (moderate to severe disability) | 16 (22.3%) |

| mRS 6 (death) | 24 (33.3%) |

| The modified ranking scale at 90 days (number 59 patients) | |

| mRS 0 - 2 (mild disability) | 22 (37.3%) |

| mRS 3 - 5 (moderate to severe disability) | 8 (13.5%) |

| mRS 6 (death) | 29 (49.2%) |

Sex and in-hospital mortality

The hospital mortality rate in males was 11 from 58 patients (18.9%) and in females 13 from 36 patients (35%) the p - value is 0.063.

Hospital and 90 days outcomes according to a combination of interventions (PCI plus MTE)

We identified 21 cases of concurrent cardio-cerebral infarction. Female 8 patients (38.1%), male 13 patients (61.9%). Interventions procedures: percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) was used to treat 21 patients: PCI with a balloon only 3(14%), PCI with aspiration only 1(5%), PCI with Bare metal stent 1(5%), PCI with Drug-eluting stent 16(76%). treated via Mechanical thrombectomy of cerebral vessels in 21 patients (100%). For the outcome of 21 patients, we can calculate the modified ranking scale (mRS) at discharge from 15 patients: mRS 0 - 2: 8(53.3%) patients, mRS 3 - 5: 7(46.7%) patients, mRS 6: 2(13.3%), the mRS at 90 days we reached from 17 patients, the mRS was 0 - 2: 7(41%) patients, 3 - 5: 6(35%) patients and 6: 4(23.5%) Patients.

The difference in mortality rate between combination intervention treatment and medical treatment. The mortality rate was significantly lower in a patient with a combination intervention group than in medical treatment). In medical group patients: 8 patients were treated with PCI plus medications and 3 treated with MTE plus medications and other patients were treated with medication alone) Table 4.

| Table 4: Mortality rate between combination intervention treatment and medical treatment. | |||

| Intervention (PCI and MTE) |

Medical treatment | p value | |

| Hospital mortality | 13.3% (2/15) |

38.6% (22/57) |

0.038 |

| 90 days mortality | 23.5% (4/17) |

59.5% (25/42) |

0.012 |

Outcome according to first presentation symptoms

First presentation myocardial infarction symptoms followed by acute ischemic stroke symptoms were reported in 18(19.1%) patients. In those patients, the most common stroke type (total: 18 cases, 14 cases were reported and 4 cases non-reported) anterior circulation (86%) with right middle cerebral artery and right internal carotid artery occlusion (RMCA: 4 patients, LMCA: 2 patients, Basilar artery 2 patients, RICA: 2) and this group had the highest mortality rate 33.3%.

The first acute ischemic stroke symptoms were followed by acute myocardial infarction symptoms in 50(53.2%) patients. The type of MI: inferior STEMI 19 patients, anterior STEMI 17 patients, Non-STEMI 13 patients, and 1 patient with high lateral STEMI. Coronary angiography to confirm the culprit lesion was reported in 28 patients (13 patients RCA and 2 Patients LCX, 11 patients LAD and 2 patients’ nonsignificant stenosis) and the mortality rate in this patient was reported in 13 patients 26%.

At the same time presentation of myocardial infarction and acute ischemic stroke symptoms in 26(27.7%) patients. the mortality rate in this patient was reported in 5 (19%).

We present a total of 94 patients with concurrent cardio-cerebral infarction and we reported multiple causes which can be categorized into five types:

1. Embolic (left ventricle thrombus in patients with previous myocardial infarction or dilated cardio-myopathy, left atrial appendage thrombus in patients with atrial fibrillation).

2. Hypotensive (patients with cardiogenic shock and heart failure).

3. Atherosclerotic (patient with hypertension, smoking, diabetes mellitus and previous coronary arterydisease).

4. Hyper coagulant states (COVID 19 infection, Polycythemia, malignancy and patent foramen ovale).

5. Mechanical complication (aortic dissection).

The left ventricular systolic dysfunction and atrial fibrillation are increasing the likelihood of embolic stroke due to thrombus formation in the left ventricle and left atrial appendage. These two phenomena have been commonly reported in this analysis.

About half of the patients presented with acute ischemic stroke symptoms followed by acute myocardial infarction symptoms 50(53.2%). In this patient, the most common MI type was inferior MI. First presentation myocardial infarction symptoms followed by acute ischemic stroke symptoms were reported in 18(19.1%) patients. In this patient, the most common stroke type is anterior circulation with the right middle cerebral artery or right internal carotid artery occlusion. At the same time presentation of myocardial infarction and acute ischemic stroke symptoms in 26(27.7%) patients.

For alteplase medication, forty-one patients were treated with intravenous alteplase (43.6%) and percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) was used to treat 29 patients (30.8%). Mechanical thrombectomy of cerebral vessels in 24 patients (25.5%). Only 21(22.3%) were treated in combination with both PCI and Mechanical thrombectomy of cerebral vessels. The main concerns about giving alteplase to patients with AIS and a history of recent MI are (Beyond the bleeding): 1. Thrombolysis-induced myocardial hemorrhage predisposing to myocardial wall rupture. 2. Possible ventricular thrombus that could be embolized because of thrombolysis. 3. Post-myocardial infarction pericarditis may become hemopericardium. According to the 2018 scientific statement guideline from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association (AHA/ASA), For patients presenting with synchronous AIS and AMI, treatment with intravenous alteplase at the dose appropriate for acute ischemic stroke, followed by the percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and stenting if indicated, is reasonable [77]. The new recommendation according to 2021 guidelines of the European Stroke Organization (ESO) on intravenous thrombolysis for acute ischemic stroke suggested that [78]: Contraindication of alteplase for patients with acute ischemic stroke of < 4.5 h duration and with history of subacute (> 6 h) ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction during the last seven days. The intravenous alteplase also has contraindications in patients with acute STEMI with recent acute ischemic stroke if the stroke duration is more than 4.5 hours from the onset of symptoms [79]. So that if AIS after 6 hours from STEMI onset, or STEMI after 4.5 hours from AIS intravenous alteplase is a contraindication. In these conditions, we recommended intervention treatment with PCI and/or MTE.

Our metanalysis showed that concurrent CCI had a high in-hospital mortality rate of 33.3% and a 3-month mortality rate of 49.2%. The in-hospital mortality rate was higher in males (35%) than in females (18.9%) and 78% of death related to cardiovascular causes. Lennie Lynn C. de Castillo, et al. in case of a series, involved 9 patients with concurrent CCI reported a mortality rate of 45% and cardiovascular death was 69% (8), In another metanalysis of 44 patients, ten patients died (23%) and nine (90%) of those were due to cardiac causes, [80]. The use of a combination of intervention reduce hospital mortality to 13.3% and 90-day mortality to 25.3%. (p value: 0.038 and 0.012 respectively).

To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest meta-analysis, on the concurrent cardio cerebral infarctions, encompassing of 94 patients. The most common co-morbidities that patients presented with included hypertension, smoking, atrial fibrillation and diabetes mellitus. A greater number of male patients were noted but the mortality rate was higher in female patient. The combination intervention (PCI and MTE) treatment was significantly reduce mortality.

The occurrence of concurrent cardio cerebral infarction is rare with high risk of mortality rate especially in female patients. The intervention with PCI and MTE was significantly reduces the mortality rate. Further studies will need to examine the optimum treatment strategies

Declaration of competing interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

- White H, Boden-Albala B, Wang C, Elkind MS, Rundek T, Wright CB, Sacco RL. Ischemic stroke subtype incidence among whites, blacks, and Hispanics: the Northern Manhattan Study. Circulation. 2005 Mar 15;111(10):1327-31. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000157736.19739.D0. PMID: 15769776.

- Zinkstok SM, Roos YB; ARTIS investigators. Early administration of aspirin in patients treated with alteplase for acute ischaemic stroke: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2012 Aug 25;380(9843):731-7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60949-0. Epub 2012 Jun 28. PMID: 22748820.

- Sandercock PA, Counsell C, Kane EJ. Anticoagulants for acute ischaemic stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Mar 12;2015(3):CD000024. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000024.pub4. Update in: Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021 Oct 22;10:CD000024. PMID: 25764172; PMCID: PMC7065522.

- Patel MR, Meine TJ, Lindblad L, Griffin J, Granger CB, Becker RC, Van de Werf F, White H, Califf RM, Harrington RA. Cardiac tamponade in the fibrinolytic era: analysis of >100,000 patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 2006 Feb;151(2):316-22. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.04.014. PMID: 16442893.

- Budaj A, Flasinska K, Gore JM, Anderson FA Jr, Dabbous OH, Spencer FA, Goldberg RJ, Fox KA; GRACE Investigators. Magnitude of and risk factors for in-hospital and postdischarge stroke in patients with acute coronary syndromes: findings from a Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events. Circulation. 2005 Jun 21;111(24):3242-7. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.512806. Epub 2005 Jun 13. PMID: 15956123.

- Habib M. Cardio-Cerebral Infarction Syndrome (CCIS): Definition, Diagnosis, Pathophysiology and Treatment. Cardiology and Cardiovascular Research. 2021; 5: 2; 84-93.

- Chong CZ, Tan BY, Sia CH, Khaing T, Litt Yeo LL. Simultaneous cardiocerebral infarctions: a five-year retrospective case series reviewing natural history. Singapore Med J. 2022 Nov;63(11):686-690. doi: 10.11622/smedj.2021043. PMID: 33866711; PMCID: PMC9815165.

- de Castillo LLC, Diestro JDB, Tuazon CAM, Sy MCC, Añonuevo JC, San Jose MCZ. Cardiocerebral Infarction: A Single Institutional Series. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2021 Jul;30(7):105831. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2021.105831. Epub 2021 Apr 30. PMID: 33940364.

- Yeo LLL, Andersson T, Yee KW, Tan BYQ, Paliwal P, Gopinathan A, Nadarajah M, Ting E, Teoh HL, Cherian R, Lundström E, Tay ELW, Sharma VK. Synchronous cardiocerebral infarction in the era of endovascular therapy: which to treat first? J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2017 Jul;44(1):104-111. doi: 10.1007/s11239-017-1484-2. PMID: 28220330.

- Bao CH, Zhang C, Wang XM, Pan YB. Concurrent acute myocardial infarction and acute ischemic stroke: Case reports and literature review. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022 Nov 1;9:1012345. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2022.1012345. PMID: 36386323; PMCID: PMC9663457.

- Habib MH. Synchronous Cardio-Cerebral Infarction Syndrome with Cardiogenic Shock. Is it Safe to Perform Rescue Percutaneous Coronary Intervention and Mechanical Thrombectomy for Middle Cerebral Artery?. EC Neurology 2022; 14:12 .

- Nakajima H, Tsuchiya T, Shimizu S, Watanabe K, Kitamura T, Suzuki H. Endovascular therapy for cardiocerebral infarction associated with atrial fibrillation: A case report and literature review. Surg Neurol Int. 2022 Oct 21;13:479. doi: 10.25259/SNI_593_2022. PMID: 36324934; PMCID: PMC9609951.

- Chong CZ, Tan BY, Sia CH, Khaing T, Litt Yeo LL. Simultaneous cardiocerebral infarctions: a five-year retrospective case series reviewing natural history. Singapore Med J. 2022 Nov;63(11):686-690. doi: 10.11622/smedj.2021043. PMID: 33866711; PMCID: PMC9815165.

- Ibekwe E, Kamdar HA, Strohm T. Cardio-cerebral infarction in left MCA strokes: a case series and literature review. Neurol Sci. 2022 Apr;43(4):2413-2422. doi: 10.1007/s10072-021-05628-x. Epub 2021 Sep 29. PMID: 34590206; PMCID: PMC8480750.

- Eskandarani R, Sahli S, Sawan S, Alsaeed A. Simultaneous cardio-cerebral infarction in the coronavirus disease pandemic era: A case series. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021 Jan 29;100(4):e24496. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000024496. PMID: 33530272; PMCID: PMC7850703.

- Iqbal P, Laswi B, Jamshaid MB, Shahzad A, Chaudhry HS, Khan D, Qamar MS, Yousaf Z. The Role of Anticoagulation in Post-COVID-19 Concomitant Stroke, Myocardial Infarction, and Left Ventricular Thrombus: A Case Report. Am J Case Rep. 2021 Jan 15;22:e928852. doi: 10.12659/AJCR.928852. PMID: 33446625; PMCID: PMC7816663.

- Abe S, Tanaka K, Yamagami H, Sonoda K, Hayashi H, Yoneda S, Toyoda K, Koga M. Simultaneous cardio-cerebral embolization associated with atrial fibrillation: a case report. BMC Neurol. 2019 Jul 5;19(1):152. doi: 10.1186/s12883-019-1388-1. PMID: 31277605; PMCID: PMC6612210.

- Katsuki M, Katsuki S. A case of cardiac tamponade during the treatment of simultaneous cardio-cerebral infarction associated with atrial fibrillation - Case report. Surg Neurol Int. 2019 Dec 6;10:241. doi: 10.25259/SNI_504_2019. PMID: 31893142; PMCID: PMC6911677.

- Gungoren F, Besli F, Tanriverdi Z, Kocaturk O. Optimal treatment modality for coexisting acute myocardial infarction and ischemic stroke. Am J Emerg Med. 2019 Apr;37(4):795.e1-795.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2018.12.060. Epub 2018 Dec 31. PMID: 30612780.

- Obaid O, Smith HR, Brancheau D. Simultaneous Acute Anterior ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction and Acute Ischemic Stroke of Left Middle Cerebral Artery: A Case Report. Am J Case Rep. 2019 Jun 2;20:776-779. doi: 10.12659/AJCR.916114. PMID: 31154453; PMCID: PMC6561139.

- Sakuta K, Mukai T, Fujii A, Makita K, Yaguchi H. Endovascular Therapy for Concurrent Cardio-Cerebral Infarction in a Patient With Trousseau Syndrome. Front Neurol. 2019 Sep 6;10:965. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2019.00965. PMID: 31555206; PMCID: PMC6742686.

- Wan Asyraf WZ, Elengoe S, Che Hassan HH, Abu Bakar A, Remli R. Concurrent stroke and ST-elevation myocardial infarction: Is it a contraindication for intravenous tenecteplase? Med J Malaysia. 2020 Mar;75(2):169-170. PMID: 32281601.

- Chen KW, Tsai KC, Hsu JY, Fan TS, Yang TF, Hsieh MY. One-Step Endovascular Salvage Revascularization for Concurrent Coronary and Cerebral Embolism. Acta Cardiol Sin. 2022 Mar;38(2):217-220. doi: 10.6515/ACS.202203_38(2).20211002A. PMID: 35273445; PMCID: PMC8888320.

- Nardai S, Vorobcsuk A, Nagy F, Vajda Z. Successful endovascular treatment of simultaneous acute ischaemic stroke and hyperacute ST-elevation myocardial infarction: the first case report of a single-operator cardio-cerebral intervention. Eur Heart J Case Rep. 2021 Oct 14;5(11):ytab419. doi: 10.1093/ehjcr/ytab419. PMID: 34746640; PMCID: PMC8567068.

- Nagao S, Tsuda Y, NarikiyoM, Nagayama G, NagasakiH, Tsuboi Y, Itou N, Kambayashi C. A case of a patient with endovascular treatment after intravenous t-PA therapy for the acute cerebral infarction and acute myocardial infarction, Japanese Journal of Stroke. 2019; 41:1; 7-12. Released on J-STAGE January 25 2019, Advance online publication May 07 2018, Online ISSN 1883-1923, Print ISSN 0912-0726.

- Cabral M, Ponciano A, Santos B, Morais J. Cardiocerebral Infarction: A Combination to Prevent. Int J Cardiovasc Sci. 2022; 01 Aug 2022. https://doi.org/10.36660/ijcs.20210276

- Plata-Corona JC, Cerón-Morales JA, Lara-Solís B. Nonhyperacute synchronous cardio-cerebral infarction treated by double intervensionist therapy. Cardiovasc Metab Sci. 2019; 30(2):66–75.

- Yeo LLL, Andersson T, Yee KW, Tan BYQ, Paliwal P, Gopinathan A, Nadarajah M, Ting E, Teoh HL, Cherian R, Lundström E, Tay ELW, Sharma VK. Synchronous cardiocerebral infarction in the era of endovascular therapy: which to treat first? J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2017 Jul;44(1):104-111. doi: 10.1007/s11239-017-1484-2. PMID: 28220330.

- Kijpaisalratana N, Chutinet A, Suwanwela NC. Hyperacute Simultaneous Cardiocerebral Infarction: Rescuing the Brain or the Heart First? Front Neurol. 2017 Dec 7;8:664. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2017.00664. PMID: 29270151; PMCID: PMC5725403.

- Hosoya H, Levine JJ, Henry DH, Goldberg S. Double the Trouble: Acute Coronary Syndrome and Ischemic Stroke in Polycythemia Vera. Am J Med. 2017 Jun;130(6):e237-e240. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.02.016. Epub 2017 Mar 14. PMID: 28302386.

- Maciel R, Palma R, Sousa P, Ferreira F, Nzwalo H. Acute stroke with concomitant acute myocardial infarction: will you thrombolyse? J Stroke. 2015 Jan;17(1):84-6. doi: 10.5853/jos.2015.17.1.84. Epub 2015 Jan 30. PMID: 25692111; PMCID: PMC4325641.

- Wee CK, Divakar Gosavi1 T, Huang W. The Clot Strikes Thrice: Case Report of a Patient with 3 Concurrent Embolic events. Acta Neurol Taiwan. 2015 Sep;24(3):92-6. PMID: 27333833.

- Tokuda K, Shindo S, Yamada K, Shirakawa M, Uchida K, Horimatsu T, Ishihara M, Yoshimura S. Acute Embolic Cerebral Infarction and Coronary Artery Embolism in a Patient with Atrial Fibrillation Caused by Similar Thrombi. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2016 Jul;25(7):1797-1799. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2016.01.055. Epub 2016 Apr 19. PMID: 27105568.

- González-Pacheco H, Méndez-Domínguez A, Vieyra-Herrera G, Azar-Manzur F, Meave-González A, Rodríguez-Zanella H, Martínez-Sánchez C. Reperfusion strategy for simultaneous ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction and acute ischemic stroke within a time window. Am J Emerg Med. 2014 Sep;32(9):1157.e1-4. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2014.02.047. Epub 2014 Mar 5. PMID: 24703066.

- Hashimoto O, Sato K, Numasawa Y, Hosokawa J, Endo M. Simultaneous onset of myocardial infarction and ischemic stroke in a patient with atrial fibrillation: multiple territory injury revealed on angiography and magnetic resonance. Int J Cardiol. 2014 Mar 15;172(2):e338-40. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.12.312. Epub 2014 Jan 17. PMID: 24495655.

- Kim HL, Seo JB, Chung WY, Zo JH, Kim MA, Kim SH. Simultaneously Presented Acute Ischemic Stroke and Non-ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction in a Patient with Paroxysmal Atrial Fibrillation. Korean Circ J. 2013 Nov;43(11):766-9. doi: 10.4070/kcj.2013.43.11.766. Epub 2013 Nov 30. PMID: 24363753; PMCID: PMC3866317.

- Kleczyński P, Dziewierz A, Rakowski T, Rzeszutko L, Sorysz D, Legutko J, Dudek D. Cardioembolic acute myocardial infarction and stroke in a patient with persistent atrial fibrillation. Int J Cardiol. 2012 Nov 29;161(3):e46-7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.04.018. Epub 2012 Apr 30. PMID: 22552166.

- Omar HR, Fathy A, Rashad R, Helal E. Concomitant acute right ventricular infarction and ischemic cerebrovascular stroke; possible explanations. Int Arch Med. 2010 Oct 26;3:25. doi: 10.1186/1755-7682-3-25. PMID: 20977759; PMCID: PMC2974668.

- Khairy M, Lu V, Ranasinghe N, Ranasinghe L. A Case Report on Concurrent Stroke and Myocardial Infarction. Asp Biomed Clin Case Rep. 2021 Jan 23;4(1):42-49.

- Kijeong L, Woohyun P, Kwon-Duk S, Hyeongsoo K. Which one to do first?: a case report of simultaneous acute ischemic stroke and myocardial infarction. Journal of Neurocritical Care. 2021; 14(2):109-112.

- Yusuf M, Pratama IS, Gunadi R, Sani AF. Hemodynamic Stroke in Simultaneous Cardio Cerebral Infarction: A New Term for Cardiologist. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2021 Aug 05; 9(C):114-117.

- Bhandari M, Pradhan AK, Vishwakarma P, Sethi R. Concurrent Coronary, Left Ventricle, and Cerebral Thrombosis - A Trilogy. Int J Appl Basic Med Res. 2022 Apr-Jun;12(2):130-133.

- Mai Duy T, DaoViet P, Nguyen Tien D, Nguyen QA, Nguyen Tat T, Hoang VA, Le Hong T, Nguyen Van H, Anh Nguyen D, Nguyen Van C, Thai Lien NV, Nga VT, Chu DT. Coronary aspiration thrombectomy after using intravenous recombinant tissue plasminogen activator in a patient with acute ischemic stroke: a case report. J Int Med Res. 2019 Sep;47(9):4551-4556. doi: 10.1177/0300060519865626. Epub 2019 Aug 15. PMID: 31416384; PMCID: PMC6753530.

- Bersano A, Melchiorre P, Moschwitis G, Tavarini F, Cereda C, Micieli G, Parati E, Bassetti C. Tako-tsubo syndrome as a consequence and cause of stroke. Funct Neurol. 2014 Apr-Jun;29(2):135-7. PMID: 25306124; PMCID: PMC4198162.

- Nishimura T, Kobashi D, Nakamura M, Takahashi Y, Maruyama J, Sasaki T. Cardio-cerebral infarction with splenic infarction, Journal of Japanese Society for Emergency Medicine. 2022; 25:1; 84-88. Released on J-STAGE February 28, 202; Online ISSN 2187-9001; Print ISSN 1345-0581. https://doi.org/10.11240/jsem.25.84.

- Grogono J, Fitzsimmons SJ, Shah BN, Rakhit DJ, Gray HH. Simultaneous myocardial infarction and ischaemic stroke secondary to paradoxical emboli through a patent foramen ovale. Clin Med (Lond). 2012 Aug;12(4):391-2. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.12-4-391. PMID: 22930890; PMCID: PMC4952134.

- Almasi M, Razmeh S, Habibi AH, Rezaee AH. Does Intravenous Administration of Recombinant Tissue Plasminogen Activator for Ischemic Stroke can Cause Inferior Myocardial Infarction? Neurol Int. 2016 Jun 29;8(2):6617. doi: 10.4081/ni.2016.6617. PMID: 27441068; PMCID: PMC4935817.

- Karunathilake P, Rajaratnam A, Kularatne WKS. Lessons learned from the management of a case of acute synchronous cardio cerebral infarction in a resource-poor setting. 09 June 2022; Preprint (Version 1).

- Taborda P, Besteiro N, Pfirter G,.Rev F. Méd. Clín. Condes. sept.-dic. 2020; 31(5/6): 487-490.

- Nguyen TL, Rajaratnam R. Dissecting out the cause: a case of concurrent acute myocardial infarction and stroke. BMJ Case Rep. 2011 Jun 3;2011:bcr0220113824. doi: 10.1136/bcr.02.2011.3824. PMID: 22693314; PMCID: PMC3109691.

- Loffi M, Besana M, Regazzoni V, Enrico P, Giuli VD. A masked ST-elevation myocardial infarction. J Clin Images Med Case Rep. 2021; 2(4): 1249.

- Yong TH, See JHJ, Liew BW. STEMI during Cardiocerebral Infarction (CCI): Is it Safe to Perform Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention?. Int J Clin Cardiol. 2022; 8:251. doi.org/10.23937/23782951/1410251.

- Kawano H, Tomichi Y, Fukae S, Koide Y, Toda G, Yano K. Aortic dissection associated with acute myocardial infarction and stroke found at autopsy. Intern Med. 2006;45(16):957-62. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.45.1589. Epub 2006 Sep 15. PMID: 16974058.

- Wang X, Li Q, Wang Y, Zhao Y, Zhou S, Luo Z, Gu M. A case report of acute simultaneous cardiocerebral infarction: possible pathophysiology. Ann Palliat Med. 2021 May;10(5):5887-5890. doi: 10.21037/apm-21-808. PMID: 34107694.

- Chlapoutakis GN, Kafkas NV, Katsanos SM, Kiriakou LG, Floros GV, Mpampalis DK. Acute myocardial infarction and transient ischemic attack in a patient with lone atrial fibrillation and normal coronary arteries. Int J Cardiol. 2010 Feb 18;139(1):e1-4. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2008.06.085. Epub 2008 Aug 19. PMID: 18715661.

- Koneru S, Jillella DV, Nogueira RG. Cardio-Cerebral Infarction, Free-Floating Thrombosis and Hyperperfusion in COVID-19. Neurol Int. 2021 Jun 11;13(2):266-268. doi: 10.3390/neurolint13020027. PMID: 34208052; PMCID: PMC8293395.

- Wallace EL, Smyth SS. Spontaneous coronary thrombosis following thrombolytic therapy for acute cardiovascular accident and stroke: a case study. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2012 Nov;34(4):548-51. doi: 10.1007/s11239-012-0754-2. PMID: 22684577; PMCID: PMC3697839.

- Meissner W, Lempert T, Saeuberlich-Knigge S, Bocksch W, Pape UF. Fatal embolic myocardial infarction after systemic thrombolysis for stroke. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2006; 22:213–214. [PubMed: 16766875].

- Sweta A, Sejal S, Prakash S, Vinay C, Shirish H. Acute myocardial infarction following intravenous tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke: An unknown danger. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2010; 13:64–66. [PubMed: 20436751].

- Yang CJ, Chen PC, Lin CS, Tsai CL, Tsai SH. Thrombolytic therapy-associated acute myocardial infarction in patients with acute ischemic stroke: A treatment dilemma. Am J Emerg Med. 2017 May;35(5):804.e1-804.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2016.11.044. Epub 2016 Nov 22. PMID: 27890301.

- Brz˛eczek M, Kidawa M, Ledakowicz-Polak A, et al. Myocardial infarction with simultaneous acute stroke in a patient with prior aortic graft replacement - what is the origin of the embolic incident? Folia Cardiol 2019;14(2):166-168.

- Manea MM, Dragoş D, Stoica E, Bucşa A, Marinică I, Tuţă S. Early ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction after thrombolytic therapy for acute ischemic stroke: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018 Dec;97(50):e13347. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000013347. PMID: 30557984; PMCID: PMC6320080.

- Cai XQ, Wen J, Zhao Y, Wu YL, Zhang HP, Zhang WZ. Acute Ischemic Stroke Following Acute Myocardial Infarction: Adding Insult to Injury. Chin Med J (Engl). 2017 May 5;130(9):1129-1130. doi: 10.4103/0366-6999.204921. PMID: 28469112; PMCID: PMC5421187.

- Fitzek S, Fitzek C. A Myocardial Infarction During Intravenous Recombinant Tissue Plasminogen Activator Infusion for Evolving Ischemic Stroke. Neurologist. 2015 Sep;20(3):46-7. doi: 10.1097/NRL.0000000000000046. PMID: 26375375.

- Mehdiratta M, Murphy C, Al-Harthi A, Teal PA. Myocardial infarction following t-PA for acute stroke. Can J Neurol Sci. 2007; 34:417–420. [PubMed: 18062448].

- Y-Hassan S, Winter R, Henareh L. The causality quandary in a patient with stroke, Takotsubo syndrome and severe coronary artery disease. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown). 2015 Jan;16 Suppl 2:S118-21. doi: 10.2459/JCM.0b013e32834037a1. PMID: 20935571.

- Wang B, Patel H, Snow T. ST-elevation myocardial infarction following thrombolysis for acute stroke: a case report. West Lond Med J. 2011; 3:7-13.

- Stafford PJ, Strachan CJ, Vincent R, Chamberlain DA. Multiple microemboli after disintegration of clot during thrombolysis for acute myocardial infarction. BMJ. 1989 Nov 25;299(6711):1310-2. doi: 10.1136/bmj.299.6711.1310. PMID: 2513932; PMCID: PMC1838196.

- Peng H, Chen M, Li G, Zhang M, Wu M, Huang H, Huang H, Ouyang F. Combination refusion therapy for a hemodynamically unstable patient with acute myocardial infarction complicated by acute ischemic stroke within a time window. Int J Cardiol. 2015 Dec 15;201:152-3. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.08.017. Epub 2015 Aug 3. PMID: 26298362.

- Chang GY. An ischemic stroke during intravenous recombinant tissue plasminogen activator infusion for evolving myocardial infarction. Eur J Neurol. 2001 May;8(3):267-8. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-1331.2001.00216.x. PMID: 11328336.

- Kawarada O, Yokoi Y. Brain salvage for cardiac cerebral embolism following myocardial infarction. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2010 Apr 1;75(5):679-83. doi: 10.1002/ccd.22330. PMID: 20020521.

- Sihite TA, Rehmenda MA, Sitepu M, Effendi CA. Review on Acute Cardio-Cerebral Infarction: a Case Report. IJIHS. 2021; 9(2):84-88

- Abuheit E, Lu F, Liu S. Mechanical thrombectomy for ischemic stroke during Percutaneous Coronary Intervention for Acute Myocardial Infarction in a three- vessel disease patient: a case report and literature review. Research Square; 2022. DOI: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-2044174/v1.

- Abdi IA, Karataş M, Abdi AE, Hassan MS, Yusuf Mohamud MF. Simultaneous acute cardio-cerebral infarction associated with isolated left ventricle non-compaction cardiomyopathy. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2022 Jul 16;80:104172. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2022.104172. PMID: 36045823; PMCID: PMC9422203.

- de Castillo LLC, Diestro JDB, Tuazon CAM, Sy MCC, Añonuevo JC, San Jose MCZ. Cardiocerebral Infarction: A Single Institutional Series. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2021 Jul;30(7):105831. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2021.105831. Epub 2021 Apr 30. PMID: 33940364.

- Habib M, Awadallah S. Acute Ischemic Stroke Followed by Acute Inferior Myocardial Infarction. Tech Neurosurg Neurol. 2022; 5(3). TNN. 000612.

- Powers WJ, Rabinstein AA, Ackerson T, Adeoye OM, Bambakidis NC, Becker K, Biller J, Brown M, Demaerschalk BM, Hoh B, Jauch EC, Kidwell CS, Leslie-Mazwi TM, Ovbiagele B, Scott PA, Sheth KN, Southerland AM, Summers DV, Tirschwell DL; American Heart Association Stroke Council. 2018 Guidelines for the Early Management of Patients With Acute Ischemic Stroke: A Guideline for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2018 Mar;49(3):e46-e110. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000158. Epub 2018 Jan 24. Erratum in: Stroke. 2018 Mar;49(3):e138. Erratum in: Stroke. 2018 Apr 18;: PMID: 29367334.

- Berge E, Whiteley W, Audebert H, De Marchis GM, Fonseca AC, Padiglioni C, de la Ossa NP, Strbian D, Tsivgoulis G, Turc G. European Stroke Organisation (ESO) guidelines on intravenous thrombolysis for acute ischaemic stroke. Eur Stroke J. 2021 Mar;6(1):I-LXII. doi: 10.1177/2396987321989865. Epub 2021 Feb 19. PMID: 33817340; PMCID: PMC7995316.

- Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, Antunes MJ, Bucciarelli-Ducci C, Bueno H, Caforio ALP, Crea F, Goudevenos JA, Halvorsen S, Hindricks G, Kastrati A, Lenzen MJ, Prescott E, Roffi M, Valgimigli M, Varenhorst C, Vranckx P, Widimský P; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2017 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation: The Task Force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2018 Jan 7;39(2):119-177. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx393. PMID: 28886621.

- Ng TP, Wong C, Leong ELE, Tan BY, Chan MY, Yeo LL, Yeo TC, Wong RC, Leow AS, Ho JS, Sia CH. Simultaneous cardio-cerebral infarction: a meta-analysis. QJM. 2022 Jun 7;115(6):374-380. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcab158. PMID: 34051098.