More Information

Submitted: April 18, 2025 | Approved: May 02, 2025 | Published: May 03, 2025

How to cite this article: Ebrahim MA, Majid H, Abdelnaby MA, Saul JP. Toddler Cavotricuspid Valve Isthmus Ablation for Typical Atrial Flutter with Cryoablation. J Cardiol Cardiovasc Med. 2025; 10(3): 057-061. Available from: https://dx.doi.org/10.29328/journal.jccm.1001210

DOI: 10.29328/journal.jccm.1001210

Copyright license: © 2025 Ebrahim MA, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Keywords: Atrial flutter; Sinus node dysfunction; AV block; Cryoablation

Abbreviations: AFL: Atrial Flutter; ASD: Atrial Septal Defect; AV: Atrioventricular; AVN: Atrioventricular Node; CTI: Cavotricuspid Isthmus; EPS: Electrophysiologic Study; SAN: Sinoatrial Node; SR: Sinus Rhythm; TEE: Transesophageal Echocardiography

Toddler Cavotricuspid Valve Isthmus Ablation for Typical Atrial Flutter with Cryoablation

Mohammad A Ebrahim1*, Hasan Majid2, Mohamed A Abdelnaby3 and J Philip Saul4

1Department of Pediatrics, Kuwait University Faculty of Medicine, Affiliated with Chest Diseases Hospital, Kuwait

2Kuwait University Faculty of Medicine, Kuwait

3Department of Pediatric Cardiology, Chest Diseases Hospital, Ministry of Health, Kuwait

4Professor of Pediatrics, West Virginia University School of Medicine, Kuwait

*Address for Correspondence: Mohammad A Ebrahim, MD, Department of Pediatrics, Kuwait University Faculty of Medicine, Affiliated with Chest Diseases Hospital, Kuwait, Email: [email protected]

Case presentation: We describe the youngest successful cavotricupsid isthmus cryoablation in a 16-month-old toddler with small atrial septal defect whose medical management was complicated by intrinsic atrioventricular nodal conduction disease and recurrent atrial flutter.

Methods: Zero fluoroscopy electrophysiology study performed. Cavotricuspid isthmus proved to be “in” circuit with entrainment. Line of block was achieved with termination of atrial flutter using 2 minutes cryolesions.

Results: The patient underwent successful cryoablation at 9 kg, without recurrence.

Conclusion: Cavotricuspid isthmus ablation using cryoablation resulted in no recurrence of atrial flutter for at least 1 year of follow up. Ablation offers a less invasive alternative to pacemaker implantation in toddlers with coexisting conduction disease, limiting medical management options.

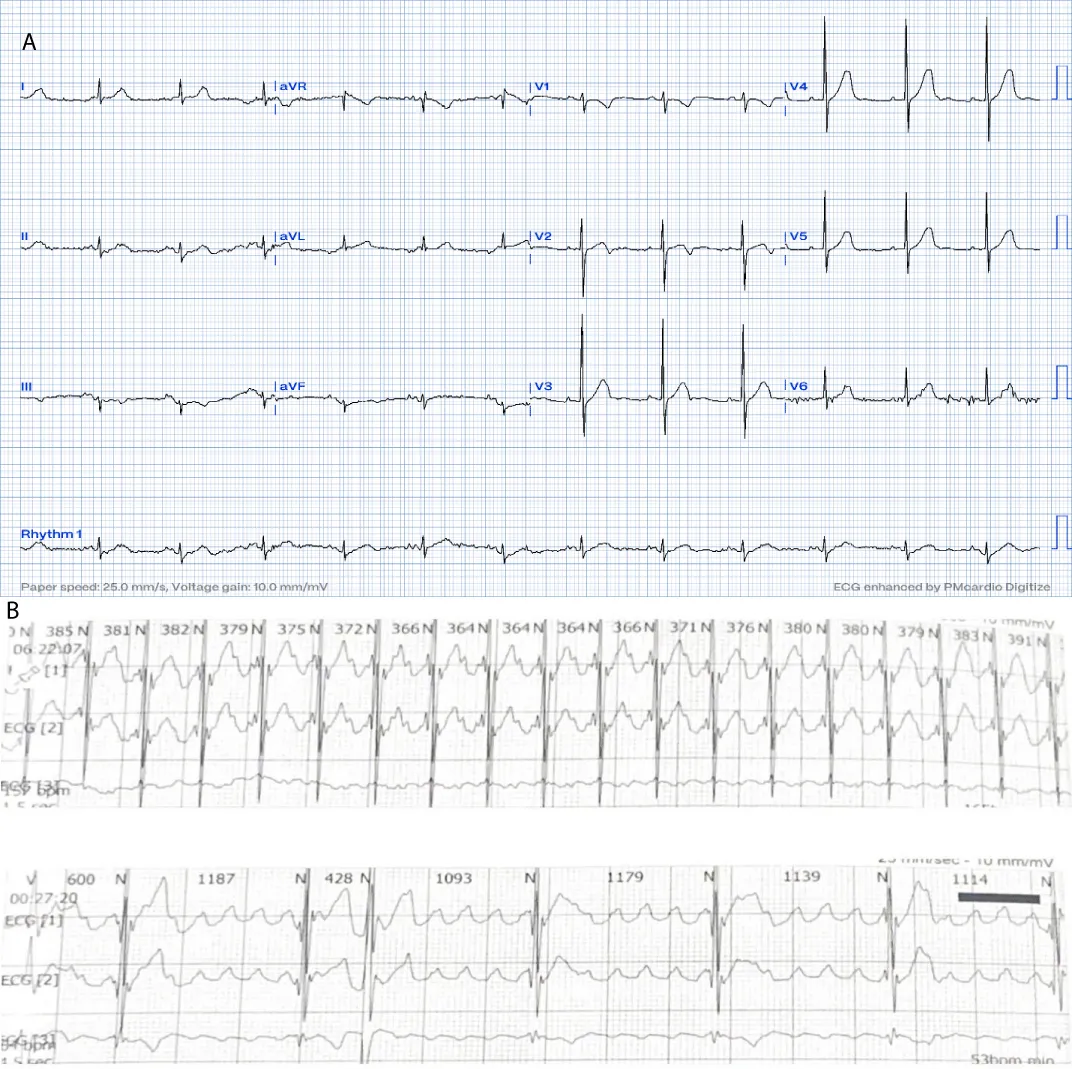

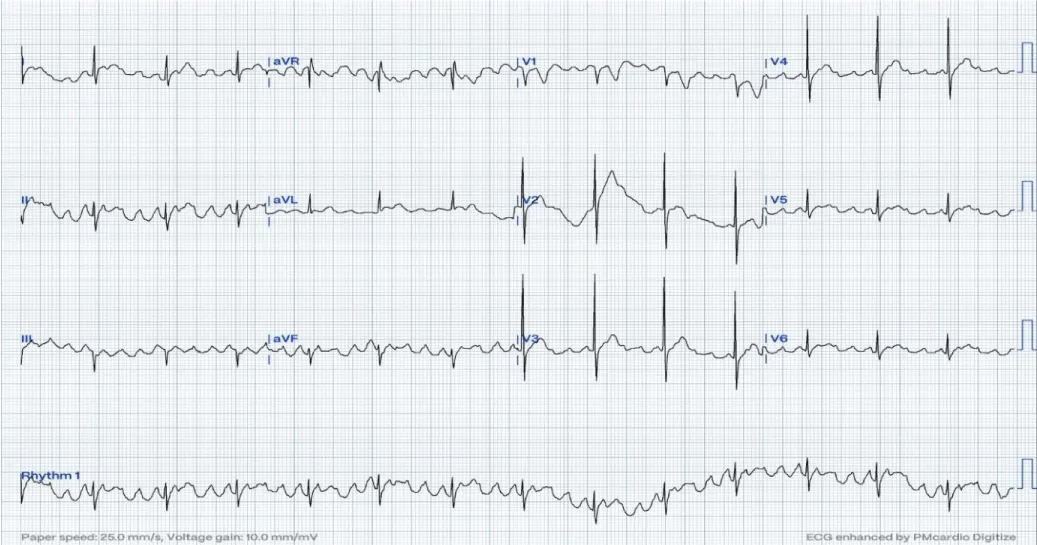

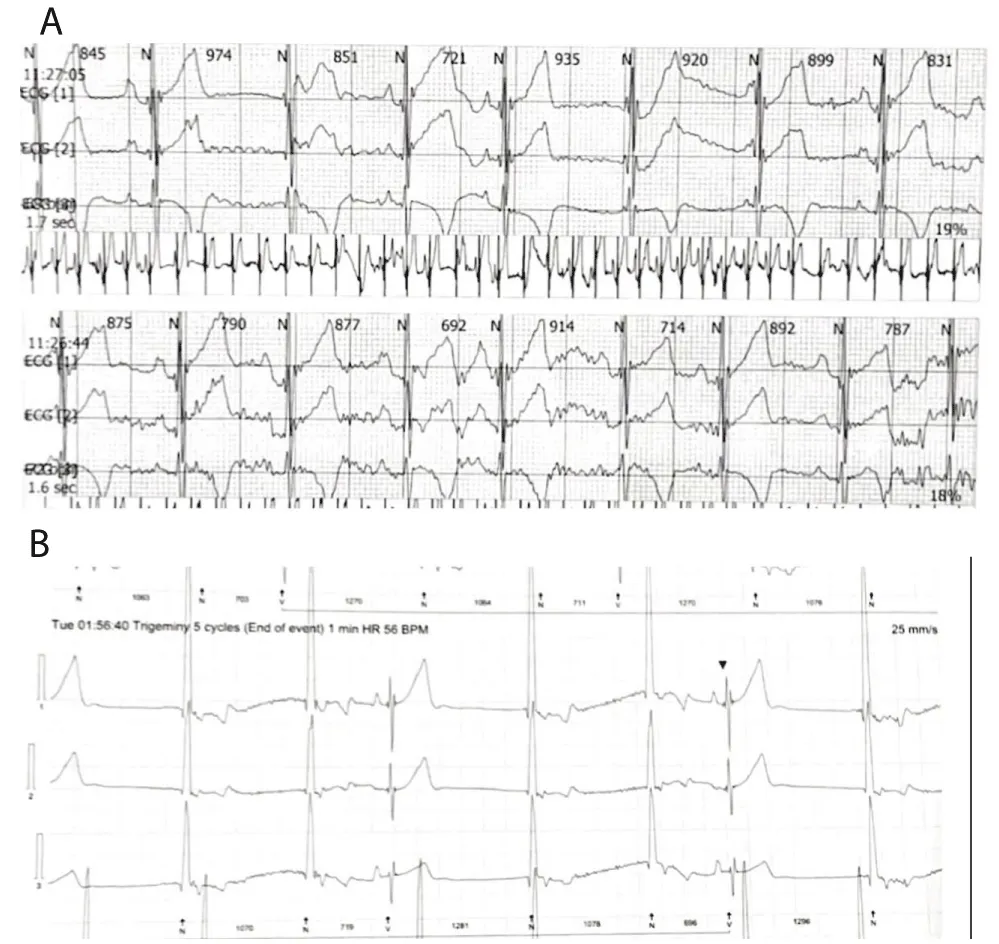

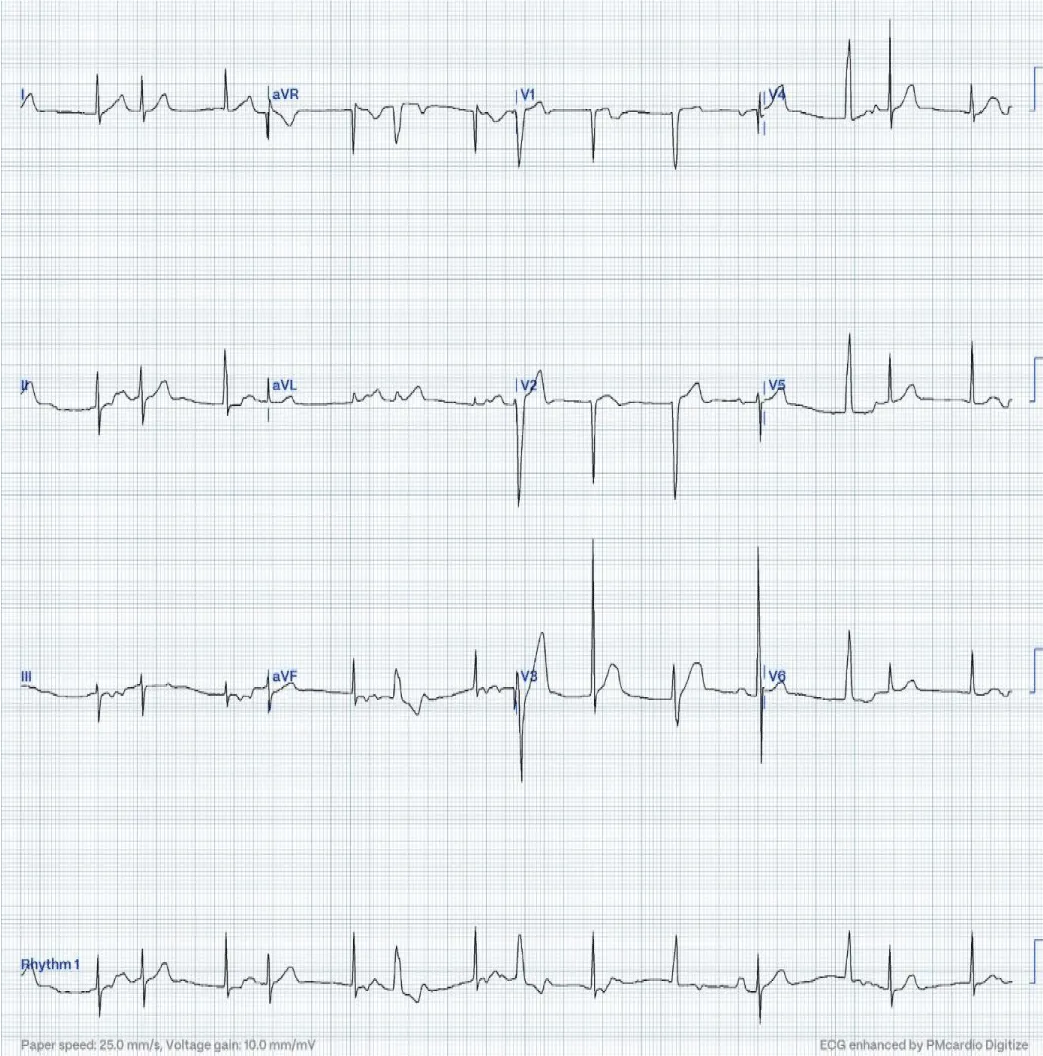

A 16-month-old child with no past medical history, referred for bradycardia. She was clinically asymptomatic except for poor growth consistent with weight and height below the third percentiles. Her ECG (Figure 1A) revealed left axis deviation, normal PR interval but with significant bradycardia indicative of Sinus Node Dysfunction (SND). Her echo revealed a small ASD but was otherwise normal. The Holter (Figure 1B) showed persistent atrial flutter (AFL), with variable degrees of block (2:1 - 6:1) and heart rates (HR) between 53-150 beats per minute (bpm). The average HR was 92 bpm despite being not on any atrioventricular nodal (AVN) blocking agent, raising concerns about intrinsic AVN dysfunction. The patient was admitted (Figure 2) for TEE to rule out intracardiac thrombi and subsequent cardioversion. She was successfully reverted to sinus rhythm, but remained bradycardic, and was started on low-dose Sotalol, at 1 mg/kg/ day, given the intrinsic conduction disease. Maternal ECG was normal, but a paternal one could not be obtained, and genetic testing was refused. Family history was otherwise unremarkable. Two months later, a follow-up Holter revealed counterclockwise AFL for which she was admitted and again cardioverted successfully. Sotalol was increased to 1.5 mg/kg/day. Over the next four months, two follow-up Holter ECGs (Figure 3) showed junctional and ventricular escape rhythms with rare sinus capture beats. Two months later, the patient came back with AFL and underwent successful cardioversion (Figure 4). The family was offered either pacemaker implantation or ablation, but initially refused both. At this point, the dose of Sotalol was increased to 2 mg/kg/day. One month later, the patient returned with persistent AFL, underwent successful cardioversion, and agreed to proceed with ablation. A zero-fluoroscopy, dual-catheter electrophysiology study (EPS) was performed using 7F Freezor™ Xtra cardiac cryoablation catheter (217F1 – 49 mm), at the age of 2 years and 10 months (9 kg). The EPS demonstrated cavotricupsid isthmus based typical AFL (proved with entrainment), and cryoablation of the isthmus resulted in termination of AFL (one application for 2 minutes per location, point by point across cavotricuspid isthmus). After ablation and while not on sotalol, the rhythm was predominantly junctional rhythm, but no recurrence of flutter was observed over the subsequent 12 months. The patient is currently approaching 4 years of age.

Figure 1: At the time of presentation. 1A: ECG shows bradycardia, left axis deviation, and negatively deflected P-waves in leads I and AVL suggesting left upper atrial focus.

Figure 2: On the first admission. The ECG reveals positive sawtooth-like F waves in the inferior leads consistent with clockwise CTI-dependent AFL at 4:1 conduction. This was cardioverted to bradycardic sinus rhythm./p>

Figure 3: These were recorded after Sotalol dose was increased after the second cardioversion. A: ECG reveals sinus pause at 974 msec, followed by re-emergence of SAN activity, but after 935 msec, the P-wave is seen marching on the QRS suggestive of sinus bradycardia with junctional escape rhythms and isorhythmic AV dissociation. Later sinus rhythm resumes intermittently. B: The QRS complexes here are relatively wider, indicating a ventricular escape origin. The third QRS is narrow and preceded immediately by a sinus beat, thus, this QRS represents a sinus capture beat./p>

Figure 4: During the third admission after cardioversion. In this ECG, the first beat is not preceded by any atrial activity and is junctional. The second beat is a conducted retrograde P wave. The third beat appears wider, seen obviously on lead II indicating a ventricular escape origin. This beat was followed by a retrograde P-wave, best seen in lead III, which was conducted anterogradely to the ventricles producing a narrow QRS complex similar to the first two beats. This QRS is described as capture-echo beat. This phenomenon occurred in the sixth and eighth beats, which were comparatively wider indicating conduction aberrancy. The thirteenth beat is another atrial capture beat.

In this ECG, the first beat is not preceded by any atrial activity and is junctional. The second beat is a conducted retrograde P wave. The third beat appears wider, seen obviously on lead II indicating a ventricular escape origin. This beat was followed by a retrograde P-wave, best seen in lead III, which was conducted anterogradely to the ventricles producing a narrow QRS complex similar to the first two beats. This QRS is described as capture-echo beat. This phenomenon occurred in the sixth and eighth beats, which were comparatively wider indicating conduction aberrancy. The thirteenth beat is another atrial capture beat.

Atrial Tachyarrhythmia (AT), including AFL, has frequently been reported to coexist with Sinus Node Dysfunction (SND) [1]. The bradycardia in SND increases the probability of atrial ectopy due to the loss of overdrive suppression, which normally inhibits subsidiary pacemaker activity [1]. On the other hand, prolonged or frequent episodes of AT have been reported to produce structural alterations that sustain the AT, including apoptosis and fibrosis, which electrically decouple the anastomosing cardiomyocytes [1]. Concomitant electrical remodeling may downregulate the inward calcium current and enhance inward rectifier potassium currents, resulting in shortened refractoriness which sustains the reentrant circuit [1]. Defective intracellular calcium handling can also lead to increased diastolic intracellular calcium concentrations and increased risk of ectopy [1]. In some cases, one factor causes or complicates the other by atrial electroanatomic and electrophysiologic remodeling, while in others, a primary atrial cardiomyopathy or inherited channelopathy produces both SND and atrial tachydysrhythmia [1]. Specifically, mutations in the SCN5A, GNB5 and the HCN genes are known to cause SND [2-4]. SCN5A mutations were reported, in a 2-year-old, to manifest sinus node dysfunction and recurrent atrial flutter [5]. Furthermore, a loss-of-function mutation in NKX2-5 has been associated with secundum ASDs and conduction defects involving the SAN and AVN [6,7]. Otherwise, SND can be associated with complex congenital heart disease or may arise secondary to cardiac surgery. Given the early age of presentation, this case is likely attributable to a genetic mutation, which could not be confirmed due to parental refusal of genetic testing. An NKX2-5 mutation could account for all the observed findings.

Conversion to and maintenance of Normal Sinus Rhythm (NSR) in patients with AFL is preferable to a rate-control strategy since it alleviates symptoms, improves functional capacity, lowers risk of tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy, and reduces the risk of systemic thromboembolic events attributable to the AFL. In patients with concurrent SND, pharmacologic cardioversion is limited by worsening of preexisting SND. Hence, pacing combined with optimized pharmacologic therapy or ablation is beneficial and were both discussed with the family. Normalizing HR through pacing may inhibit AFL development and allow for appropriate dosing of medications. However, given the age of the patient, an epicardial pacemaker would have been the most appropriate option, requiring a surgical approach. Hence, the family elected for ablation to prevent AFL development and to monitor the HR off medications.

Pacing is the only effective modality for symptomatic SND and all the reversible causes are excluded, but our patient had concurrent AFL [1]. Considering the patient’s size and age, cryoablation was thought to be the safest approach for this patient and perhaps less risk for coronary artery injury compared to radiofrequency approach [8]. Cryolesions produce well-defined fibrotic scars that do not disrupt the ultrastructure of collagen, thus, cryoablation is less likely to damage or cause persistent luminal stenosis of the adjacent blood vessels [9]. Cryoablation is also associated with significantly reduced fluoroscopy exposure and lower risk of coronary injury [10,11].

In conclusion, cavotricuspid isthmus ablation using cryoablation resulted in no recurrence of atrial flutter for at least 1 year of follow up without post-procedural complications. Ablation represents a less invasive alternative to pacemaker implantation to toddlers with coexisting conduction disease, which limits the options for medical management. The treatment allowed for discontinuation of antiarrhythmic therapy and avoiding both adverse drug effects and the need for invasive pacing. The patient has remained asymptomatic on follow-up with preserved cardiac function.

- John RM, Kumar S. Sinus node and atrial arrhythmias. Circulation. 2016;133(19):1892–1900. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.116.018011

- Adsit GS, Vaidyanathan R, Galler CM, Kyle JW, Makielski JC. Channelopathies from mutations in the cardiac sodium channel protein complex. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2013;61:34–43. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yjmcc.2013.03.017

- Lodder EM, De Nittis P, Koopman CD, Bezzina CR, Bakkers J, Merla G. GNB5 mutations cause an autosomal-recessive multisystem syndrome with sinus bradycardia and cognitive disability. Am J Hum Genet. 2016;99(3):704–710. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.06.025

- Duhme N, Schweizer PA, Thomas D, Becker R, Schröter J, Barends TRM, et al. Altered HCN4 channel C-linker interaction is associated with familial tachycardia–bradycardia syndrome and atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J. 2012;34(35):2768–2775. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehs391

- De Filippo P, Ferrari P, Iascone M, Racheli M, Senni M. Cavotricuspid isthmus ablation and subcutaneous monitoring device implantation in a 2-year-old baby with 2 SCN5A mutations, sinus node dysfunction, atrial flutter recurrences, and drug-induced long-QT syndrome: A tricky case of pediatric overlap syndrome? J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2014;26(3):346–349. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/jce.12570

- Gutierrez-Roelens I, De Roy L, Ovaert C, Sluysmans T, Devriendt K, Brunner HG. A novel CSX/NKX2-5 mutation causes autosomal-dominant AV block: are atrial fibrillation and syncopes part of the phenotype? Eur J Hum Genet. 2006;14(12):1313–1316. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201702

- Rozqie R, Satwiko MG, Anggrahini DW, Hartopo AB, Sadewa AH, Mumpuni H, et al. A novel NKX2–5 double variant corresponds with familial atrial septal defect with arrhythmia in Indonesia. Eur Heart J. 2021;42(Supplement_1). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab724.2517

- Walsh MA, Gonzalez CM, Uzun OJ, McMahon CJ, Sadagopan SN, Yue AM, et al. Outcomes from pediatric ablation. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2021;7(11):1358–1365. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacep.2021.03.012

- Issa ZF, Miller JM, Zipes DP. Ablation energy sources. In: Elsevier eBooks. 2019;206–237. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-323-52356-1.00007-4

- Jabarkhyl D, Khan MKU, Haider N, Farah A, Yusuf M, Ali N. Cryoablation versus radiofrequency ablation in the management of pediatric supraventricular tachyarrhythmia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cureus. 2025. Available from: https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.77812

- Schneider HE, Stahl M, Kriebel T, Schillinger W, Schill M, Jakobi J, et al. Double cryoenergy application (Freeze–Thaw–Freeze) at growing myocardium: lesion volume and effects on coronary arteries early after energy application. Implications for efficacy and safety in pediatric patients. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2013;24(6):701–707. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/jce.12085