More Information

Submitted: April 28, 2025 | Approved: May 16, 2025 | Published: May 19, 2025

How to cite this article: Abdelsayed M, Antzelevitch C. From Beat to Beat: How Electrolytes Shape the Heart’s Rhythmic Symphony and Structure. J Cardiol Cardiovasc Med. 2025; 10(3): 070-088. Available from: https://dx.doi.org/10.29328/journal.jccm.1001212

DOI: 10.29328/journal.jccm.1001212

Copyright license: © 2025 Abdelsayed M, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Abbreviations: APD: Action Potential Duration; CICR: Calcium-Induced Calcium Release; CFTR: Cystic Fibrosis Transmembrane conductance Regulator; HCN: Hyperpolarization-activated Cyclic Nucleotide-gated; ECG: Electrocardiography; SAN: Sinoatrial; AV: Atrioventricular; PVC: Premature Ventricular Contraction; CAP: Concentrated Ambient Particles; MCU: Mitochondrial Calcium Uniporter; MACE: Major Adverse Cardiac Events; CVD: Cardiovascular Disease; HF: Heart Failure; EEG: Electroencephalographic; CVD: Cardiovascular Disease; ICUs: Intensive Care Units; Na+: Sodium; K+: Potassium; Ca²+: Calcium; Mg²+: Magnesium; Cl-: Chloride; NO+: Nitrogen Dioxide; CDI: Calcium-Dependent Inactivation; cAMP: cyclic AMP; ECM: Extracellular Matrix

From Beat to Beat: How Electrolytes Shape the Heart’s Rhythmic Symphony and Structure

Mena Abdelsayed1 and Charles Antzelevitch1,2*

1Lankenau Institute for Medical Research and Lankenau Heart Institute, Wynnewood, PA, USA

2Sidney Kimmel Medical College of Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, PA, USA

*Address for Correspondence: Charles Antzelevitch, Lankenau Institute for Medical Research and Lankenau Heart Institute, Wynnewood, PA, USA, Email: [email protected]

Cardiac rhythm is fundamental to cardiovascular health, ensuring synchronized electrical impulses that maintain effective heartbeats and blood circulation. Central to this process are electrolytes— Sodium (Na+), Potassium (K+), Calcium (Ca²+), Magnesium (Mg²+), and Chloride (Cl-) —which regulate the generation and propagation of action potentials across cardiac cell membranes. Each electrolyte plays a distinct role in cardiac electrophysiology: Na+ drives rapid depolarization, K+ facilitates repolarization, Ca²+ modulates contraction, Mg²+ stabilizes ion channels, and Cl- maintains ionic balance. Electrolyte imbalances, such as hyperkalemia, hypokalemia, hypernatremia, and hypocalcemia, are critical contributors to arrhythmias, contractility issues, and cardiomyopathies. For instance, hyperkalemia actually depresses the upstroke of the action potential by partially depolarizing the resting membrane (inactivating Na+ channels), slowing impulse conduction. Similarly, hypercalcemia shortens Action Potential Duration (APD), while hypocalcemia compromises cardiac contractility. Clinically, maintaining electrolyte homeostasis is critical to mitigating arrhythmic risk and improving outcomes in conditions such as atrial fibrillation and Heart Failure (HF). Advances in therapeutic interventions, including electrolyte supplementation, ion channel modulators, and precision medicine approaches, offer new opportunities for improving cardiac care. Furthermore, understanding the interplay between electrolytes, myocardial ultrastructure, and systemic comorbidities like hypertension and diabetes is critical for developing targeted therapies. This review highlights the pivotal roles of electrolytes in maintaining cardiac rhythm and provides insights into their clinical and therapeutic implications for managing electrolyte-driven cardiac diseases.

• Electrolyte roles in cardiac function

o Sodium (Na⁺) — Critical for initiating the cardiac action potential during Phase 0 of depolarization. Voltage-gated Na⁺ channels facilitate rapid Na⁺ influx, enabling electrical signal propagation and synchronized cardiac contractions. Na⁺ also influences conduction velocity.

o Potassium (K⁺) — Essential for maintaining the resting membrane potential (Phase 4) and repolarization (Phase 3). K⁺ efflux during repolarization shapes APD, with abnormalities linked to arrhythmias, including long QT and short QT syndromes.

o Calcium (Ca²⁺) — Integral to the plateau phase (Phase 2) of the action potential, facilitating excitation-contraction coupling. Ca²⁺ binds to troponin C, initiating cross-bridge cycling for muscle contraction.

o Magnesium (Mg²⁺) — Modulates ion channels (e.g., L-type Ca²⁺ channels, Na⁺ - K⁺ pump), stabilizes resting membrane potential, and regulates K⁺ and Ca²⁺ balance. It prevents arrhythmias and supports myocardial energy metabolism.

o Chloride (Cl⁻) — Contributes to early repolarization (Phase 1) and resting membrane potential. Its currents influence cellular excitability and electrical stability in cardiac cells.

• Electrolyte Imbalances and Their Consequences:

o Na⁺ imbalances (hypernatremia/hyponatremia) affect conduction velocity and are linked to atrial fibrillation and ventricular arrhythmias.

o K⁺ disturbances (hyperkalemia/hypokalemia) disrupt repolarization, increasing risk for lethal arrhythmias like torsades de pointes.

o Ca²⁺ imbalances (hypercalcemia/hypocalcemia) impair contractility and may prolong the QT interval, contributing to bradyarrhythmias and AV block.

o Mg²⁺ deficiency predisposes individuals to atrial fibrillation and torsades de pointes.

o Abnormal Cl⁻ levels affect electrical stability, leading to arrhythmias.

• Clinical Implications:

o Monitoring and correcting electrolyte levels, using Mg²⁺ and K⁺ supplementation or Ca²⁺ channel blockers, reduces arrhythmias and improves outcomes in conditions such as atrial fibrillation and myocardial infarction.

• Future research Directions:

o Investigating molecular mechanisms of electrolyte-ion channel interactions.

o Developing precision therapies targeting electrolyte-driven abnormalities.

o Exploring the impact of systemic diseases (e.g., diabetes, hypertension) on electrolyte homeostasis and cardiac structure.

Cardiac electrophysiology forms the foundation of cardiovascular health by ensuring the precise coordination of electrical impulses that regulate heart rhythm and maintain effective blood circulation. This a complex and dynamic process is essential for the proper functioning of the cardiovascular system, as disruptions can lead to a wide array of clinical complications, including arrhythmias and HF [1-3]. Cardiac rhythm originates in the Sinoatrial Node (SAN), which acts as the primary pacemaker of the heart, and propagates through the myocardium to synchronize cardiac muscle contractions, enabling efficient blood pumping to vital organs [2,4]. Deviations from this tightly regulated rhythm—arising from genetic, molecular, or environmental factors—can result in a spectrum of conditions from benign arrhythmias to life-threatening emergencies [3,5].

Circadian rhythms significantly influence cardiac electrophysiological properties, modulating the heart’s susceptibility to arrhythmias. These rhythms, governed by both central and intrinsic cardiac clocks, regulate processes such as ion channel activity, electrical conduction, and myocardial excitability [5,6]. Disruptions in circadian rhythms have been linked to altered cardiac electrical stability and arrhythmogenesis, emphasizing the need to align treatment strategies with circadian rhythms [5]. Additionally, environmental factors such as air pollution have emerged as important modulators of cardiac electrophysiology [7]. Exposure to particulate matter (PM2.5) and gaseous pollutants like Nitrogen Dioxide (NO₂) has been associated with changes in repolarization dynamics, QT interval prolongation, and increased incidence of arrhythmias [8]. Mechanistically, air pollution exerts its effects via oxidative stress, systemic inflammation, and autonomic nervous system dysregulation, all of which contribute to the heightened risk of arrhythmias [9].

At the cellular level, cardiac rhythm is orchestrated by the synchronized activity of ion channels and the movement of electrolytes across cell membranes. The cardiac action potential, which drives muscle contraction and relaxation, is divided into five distinct phases (0 to 4), each characterized by specific ionic currents [1,10]. Na⁺, K⁺, Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, and Cl⁻ are the principal electrolytes involved in the generation and propagation of these action potentials [1,11]. Their precise regulation is critical for maintaining the electrical stability of cardiomyocytes, as even minor imbalances can lead to significant electrophysiological disturbances [12,13].

Na⁺ ions play a pivotal role in the initiation of the cardiac action potential, with their rapid influx during Phase 0 driving the depolarization of the membrane [1,10]. This process is critical for the propagation of electrical impulses and the synchronization of myocardial contractions [14]. Abnormalities in Na⁺ levels, such as hypernatremia or hyponatremia, can disrupt conduction velocity and increase the risk of arrhythmias [15,16]. Similarly, K⁺ ions are indispensable for repolarization phases, contributing to both the early repolarization (Phase 1) and the rapid repolarization (Phase 3) of the action potential [1,17]. Dyskalemia, encompassing hyperkalemia and hypokalemia, has profound effects on cardiac electrophysiology, as it can alter APD and predispose to life-threatening arrhythmias such as ventricular fibrillation and torsades de pointes [18,19].

Ca²⁺ ions are also essential, particularly during the plateau phase (Phase 2), where their influx through L-type Ca²⁺ channels sustains depolarization and triggers Ca²⁺-Induced Calcium Release (CICR) from the sarcoplasmic reticulum, a process integral to excitation-contraction coupling [20,21]. Imbalances in Ca²⁺ levels, such as hypercalcemia or hypocalcemia, can significantly impact cardiac contractility and rhythm, leading to conditions like bradyarrhythmias, prolonged QT intervals, or even HF [22,23]. Mg²⁺, often referredF to as the “master cation,” plays a modulatory role by stabilizing cell membranes and influencing the activity of ion channels, including those for K⁺ and Ca²⁺ [24,25]. Hypomagnesemia has been associated with increased susceptibility to arrhythmias in patients with acute myocardial infarction and atrial fibrillation [26,27].

Cl⁻ ions, though less discussed, are essential for maintaining the resting membrane potential and modulating action potential dynamics. Cl⁻ channels, including the Cystic Fibrosis Transmembrane conductance Regulator (CFTR), influence the repolarization process and are implicated in the pathophysiology of arrhythmias and HF [21,28]. Disruptions in Cl- homeostasis can lead to significant changes in cardiac excitability and conduction, further underscoring the importance of this electrolyte in cardiac physiology [29,30].

The interplay between these electrolytes and the cardiac ultrastructure, including sarcomeres, T-tubules, and intercalated discs, is crucial. Their interaction further highlights the importance of maintaining cardiac function. Ca²⁺ ions, for example, are crucial for sarcomere contraction, while Na⁺ and K⁺ gradients drive the generation and propagation of action potentials through the T-tubules [31]. Electrolyte imbalances can disrupt these ultrastructural elements, impairing myocardial contractility and energy metabolism, and contributing to the development of cardiomyopathies [32,33].

The precise regulation of electrolytes is fundamental to cardiac electrophysiology and overall cardiovascular health. Disruptions in electrolyte homeostasis, whether due to genetic, environmental, or systemic factors, can significantly impact cardiac rhythm and function, leading to a range of clinical complications. Understanding the intricate roles of these electrolytes in cardiac physiology is critical for developing targeted therapies to address arrhythmias and other cardiac disorders, particularly as new insights into their molecular and cellular mechanisms continue to emerge [3,34].

This review begins by outlining the fundamental electrophysiological roles of key electrolytes in cardiac action potential generation and propagation, then explores the specific effects of electrolyte imbalances on arrhythmogenesis, examines how individual ion channels mediate these effects, and concludes with clinical implications and emerging therapeutic strategies.

Basic physiology of cellular action potentials

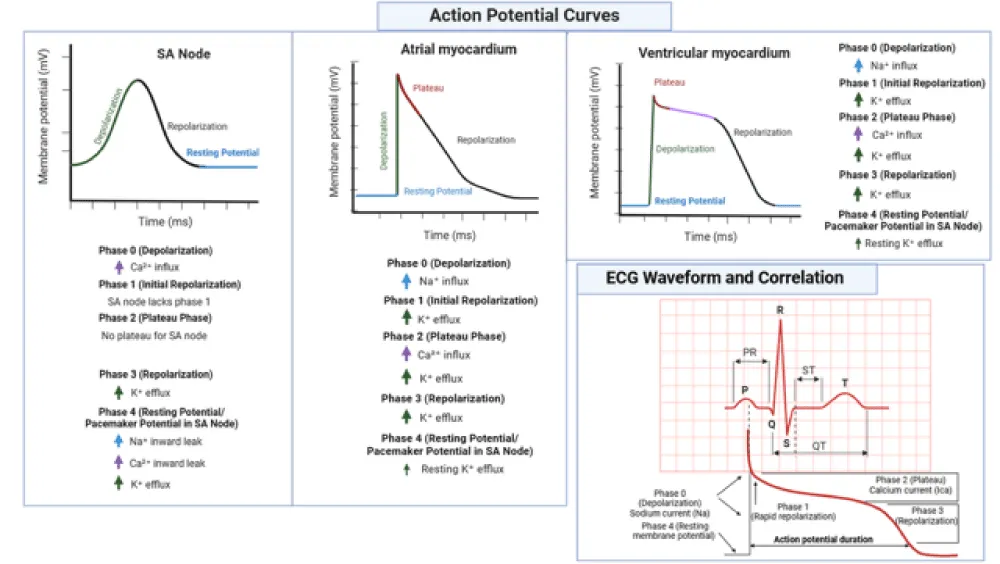

The cardiac action potential is a complex, precisely orchestrated sequence of ionic movements that underpins the contraction and relaxation of cardiac muscle cells. It is divided into five distinct phases (0 to 4), each characterized by specific ionic fluxes facilitated by the coordinated activity of ion channels and transporters. Figure 1 illustrates the action potential curves in different cardiac tissues—including the SA node, atrial and ventricular myocardium—highlighting the associated ion movements and their correlation with the ECG waveform. Electrolytes such as Na⁺, K⁺, and Ca²⁺ play critical roles in shaping these phases, while Mg²⁺, and Cl⁻ play modulatory roles [1,10,11]. The following discussion delineates the physiological mechanisms underlying each phase and highlights the pivotal contributions of these electrolytes (Table 1).

Figure 1: Action potential curves across distinct cardiac tissues and their correlation with ECG waveform. Shown are the membrane potential profiles for the SA node, atrial myocardium, and ventricular myocardium, each with annotated phases (0–4) and corresponding ionic fluxes. The figure also links action potential phases to the ECG waveform, depicting how Na+, Ca²+, and K+ currents influence depolarization, repolarization, and resting states. The SA node notably lacks a plateau phase and Phase 1 repolarization, reflecting its unique pacemaker activity. This schematic underscores the electrophysiological diversity of cardiac tissues and the critical role of electrolytes in shaping cardiac rhythm./p>

| Table 1: Electrolytes and Their Key Roles in Cardiac Action Potential Phases | ||

| Electrolyte | Phase | Role |

| Na⁺ | Phase 0 | Rapid depolarization. |

| K⁺ | Phases 1, 3, and 4 | Repolarization and resting membrane potential. |

| Ca²⁺ | Phase 2 | Plateau phase and excitation-contraction coupling. |

| Cl⁻ | Phase 1 | Early repolarization stabilization. |

| Mg²⁺ | All phases (modulatory) | Modulation of ion channel activity. |

Phase 0: Rapid depolarization

Phase 0 represents the initiation of the cardiac action potential and is marked by a rapid depolarization of the cardiac cell membrane. This phase is primarily mediated by the opening of voltage-gated Na⁺ channels (Nav1.5), which permit a substantial influx of Na⁺ ions into the cell, raising the membrane potential from its resting state to a more positive level [1,10,14]. The resulting Na⁺ current (INa) is the dominant ionic current during Phase 0 and is essential for the propagation of electrical impulses across cardiac tissue, enabling synchronized contraction of the myocardium [10,15].

Na⁺ channel activity also influences the conduction velocity of the electrical impulse, with rapid Na⁺ influx ensuring swift depolarization and efficient signal propagation through the cardiac conduction system [14,15]. Alterations in Na⁺ channel function, whether due to genetic mutations or pathological conditions, can impair conduction velocity and predispose the heart to arrhythmias, underscoring the critical role of Na⁺ in Phase 0 [14,15].

Phase 1: Early repolarization

Following the peak of the action potential, Phase 1 signifies the early repolarization of the cardiac cell membrane. This phase is characterized by the activation of the transient outward K⁺ current (ITo), which mediates the rapid efflux of K⁺ ions, contributing to a partial return of the membrane potential toward its resting state [11,17]. The Ito current activates and inactivates rapidly, and its activity is essential for shaping the characteristic notch observed at the onset of the repolarization phase [11,17].

Cl⁻ ions also play a supportive role during Phase 1 by entering the cell, balancing the outward K⁺ flux and thereby stabilizing the repolarization process [11,12]. The interplay between K⁺ and Cl⁻ currents ensures the appropriate transition from depolarization to the plateau phase and prevents premature repolarization, which could otherwise disrupt cardiac rhythm [11].

Phase 2: Plateau phase

The plateau phase, or Phase 2, is a prolonged period of depolarization that is vital for effective contraction of the cardiac muscle. This phase is primarily sustained by the influx of Ca²⁺ ions through L-type Ca²⁺ channels (ICa,L), resulting in a steady Ca²⁺ current (ICa) that maintains the depolarized state of the membrane [1,10]. The entry of Ca²⁺ ions during this phase also triggers CICR from the sarcoplasmic reticulum, a process critical for excitation-contraction coupling [20,21].

K⁺ currents, particularly the slow delayed rectifier K⁺ current (IKs), contribute to the plateau phase by balancing the inward Ca²⁺ flux and facilitating the gradual repolarization of the membrane [10,17]. This delicate balance between Ca²⁺ influx and K⁺ efflux maintains a physiologically appropriate plateau duration, which is essential for proper myocardial contraction and relaxation [1,21].

Phase 3: Rapid repolarization

Phase 3 signifies the rapid repolarization of the cardiac cell membrane, returning the membrane potential to its resting state. This phase is dominated by the activation of the rapid delayed rectifier K⁺ current (IKr) and the IKs, which mediate the outward flow of K⁺ ions [10,17]. The combined activity of these currents ensures a rapid and well-regulated repolarization process, which is critical for terminating the action potential and preparing the cell for the next depolarization cycle [10,11].

Disruptions in K⁺ channel function, whether due to genetic mutations or pharmacological agents, can impair repolarization and lead to life-threatening arrhythmias such as torsades de pointes, as observed in long QT syndrome [35,36]. Conversely, excessive K⁺ efflux can result in abbreviated APD, contributing to arrhythmogenesis in short QT syndrome [36].

Phase 4: Resting membrane potential and pacemaker potential

The final phase, Phase 4, represents the resting membrane potential in non-pacemaker cells and the pacemaker potential in specialized pacemaker cells such as those in the SAN. In non-pacemaker cells, the resting membrane potential is maintained by the inward rectifier K⁺ current (IKI), which stabilizes the membrane potential near the equilibrium potential for K⁺ ions [1,10,37].

In pacemaker cells, Phase 4 is characterized by a slow depolarization due to the inward movement of Na⁺ and Ca²⁺ ions through Hyperpolarization-activated Cyclic Nucleotide-gated (HCN) channels, which generate the hyperpolarization-activated current (If, or ‘funny current’) [38]. This gradual depolarization eventually triggers the opening of voltage-gated Ca²⁺ channels, initiating the next action potential [38].

The orchestration of these ionic currents ensures the rhythmic and automatic firing of pacemaker cells, which is essential for maintaining heart rate and rhythm. Dysregulation of these currents, whether due to electrolyte imbalances or pathological conditions, can impair pacemaker activity and lead to arrhythmias such as bradycardia or tachycardia [39,40].

Electrolyte-Specific Contributions to Cardiac Rhythm and the Pathophysiological Effects of Their Imbalances

The following sections examine each major electrolyte—Na⁺, Ca²⁺, K⁺, Mg²⁺, and Cl-—highlighting their specific roles in cardiac rhythm and how their imbalances precipitate electrophysiological disturbances.

Na+’s role in cardiac electrophysiology

Na⁺ plays a pivotal role in the initiation and propagation of cardiac action potentials, a process critical for maintaining normal heart rhythm and efficient cardiac output. During Phase 0 of the cardiac action potential, Nav1.5 opens in response to a triggering event, allowing a rapid influx of Na⁺ ions into the cell [1,10]. This rapid influx depolarizes the membrane, creating the sharp rise in membrane potential that serves as the foundation for electrical signal propagation in the heart [14]. The speed and efficiency of this process are key determinants of cardiac conduction velocity, ensuring synchronized contraction of the atria and ventricles [15]. Any disruption in Na⁺ channel function or Na⁺ homeostasis can compromise this delicate balance, leading to significant cardiac dysfunction and arrhythmias [1,14].

The physiological serum Na⁺ concentration typically ranges from 135 to 145 mEq/L, with deviations from this range resulting in hypernatremia (serum Na⁺ > 145 mmol/L) or hyponatremia (< 135 mmol/L) [41]. These electrolyte disturbances can profoundly affect cardiac electrophysiology by altering cellular excitability, conduction, and APD [15,16]. Na⁺ imbalances are often secondary to underlying conditions such as dehydration, endocrine disorders, or renal dysfunction, with distinct clinical manifestations and cardiovascular implications [16,42].

Hypernatremia, categorized into mild (151–155 mmol/L), moderate (156–160 mmol/L), and severe (> 160 mmol/L), is frequently associated with conditions such as dehydration, diabetes insipidus, and primary hyperaldosteronism [43,44]. In primary hyperaldosteronism, excessive aldosterone secretion promotes Na⁺ retention while enhancing K⁺ excretion, contributing to hypernatremia and its cardiovascular complications, including hypertension and increased arterial stiffness [42,45]. Similarly, Cushing’s syndrome, characterized by excessive cortisol production, exacerbates hypernatremia by augmenting Na⁺ reabsorption, further raising blood pressure and heightening the risk of cardiovascular disease [42]. Mechanistically, hypernatremia disrupts cellular osmotic gradients, leading to cellular dehydration, which adversely affects cardiac myocyte function and increases susceptibility to arrhythmias [16].

The clinical presentation of hypernatremia includes a spectrum of cardiovascular and neurological disturbances. Elevated sodium levels have been linked to increased mortality and prolonged hospital stays, particularly in intensive care unit patients receiving mechanical ventilation [46]. In patients with atrial fibrillation without HF, hypernatremia is associated with higher in-hospital mortality rates and greater healthcare costs [47]. Moreover, hypernatremia following cardiac surgery has been implicated in adverse neurological outcomes, including Electroencephalographic (EEG) abnormalities and brain injuries, which can indirectly impair cardiac function [48]. Immediate management strategies for severe hypernatremia focus on cautious correction of Na⁺ levels to avoid complications such as cerebral edema, hemorrhage, or osmotic demyelination, with concurrent treatment of the underlying cause [43,44].

Conversely, hyponatremia, the most common electrolyte disorder in hospitalized patients, is often a predictor of poor outcomes in cardiovascular and renal conditions [49]. In patients with acute kidney injury, hyponatremia exacerbates cardiac dysfunction by impairing Na⁺-dependent cellular processes and disrupting action potential propagation [49]. Furthermore, in patients with atrial fibrillation without HF, hyponatremia is associated with increased all-cause mortality within 365 days post-discharge, underscoring its prognostic significance in cardiac health [50]. The U-shaped relationship between serum Na⁺ levels and mortality highlights the necessity of maintaining Na⁺ balance within the physiological range to optimize cardiac function [50].

Endocrine disorders such as Conn’s syndrome, a condition marked by aldosterone overproduction, further illustrate the interplay between Na⁺ homeostasis and cardiac health. In Conn’s syndrome, excessive Na⁺ and water retention lead to volume overload, hypertension, and left ventricular hypertrophy, increasing the risk of arrhythmias and HF [42]. Similarly, Cushing’s syndrome contributes to Na⁺ imbalances through cortisol-mediated effects on renal Na⁺ transporters, aggravating cardiovascular morbidity and mortality [16].

The electrophysiological consequences of Na⁺ imbalances are evident on Electrocardiography (ECG). Hypernatremia may induce wide QRS complexes and inverted T waves, reflecting alterations in ventricular depolarization and repolarization [41]. In contrast, hyponatremia can reduce action potential amplitude and conduction velocity, predisposing to atrial and ventricular arrhythmias [41]. These ECG changes serve as valuable diagnostic markers for detecting Na⁺-related cardiac disturbances [41].

Na⁺ is integral to cardiac electrophysiology, with deviations from its physiological range significantly affect heart function. Conditions such as hypernatremia and hyponatremia, often secondary to endocrine or renal pathologies, underscore the importance of Na⁺ homeostasis in maintaining cardiac health. The management of Na⁺ imbalances requires a nuanced approach, balancing the correction of serum Na⁺ levels with the treatment of underlying etiologies to minimize cardiovascular risks and improve patient outcomes [16,43].

Ca²+’s role in cardiac electrophysiology

Ca²⁺ are central to cardiac physiology, playing pivotal roles in action potential generation, excitation-contraction coupling, and overall myocardial function [20,51]. During the plateau phase (Phase 2) of the cardiac action potential, the influx of Ca²⁺ through voltage-gated L-type Ca²⁺ channels, primarily Cav1.2, sustains depolarization and triggers downstream processes necessary for cardiac contraction [1,21]. This Ca²⁺ influx activates a phenomenon known as CICR from the sarcoplasmic reticulum, facilitating myocardial contraction by enabling Ca²⁺ binding to troponin on actin filaments [20,51]. Dysregulation of this finely tuned system has significant consequences for cardiac rhythm and contractility, often manifesting as arrhythmias or HF [22,51].

The Cav1.2 channel is ubiquitously expressed in the myocardium and is essential for the electrical and mechanical coupling of cardiac cells [21]. The activity of Cav1.2 is tightly regulated by intracellular Ca²⁺, which undergoes Ca²⁺-Dependent Inactivation (CDI), which modulates channel activity to prevent excessive Ca²⁺ entry and ensure the proper duration of the action potential [20,52]. Dysregulation of Cav1.2 channels, as seen in pathological conditions such as myocardial hypertrophy, can exacerbate Ca²⁺ overload, leading to impaired myocardial function [21,52].

In addition to Cav1.2, other Ca²⁺ channels, such as Cav1.3 and Cav3.1, play specialized roles in cardiac electrophysiology. Cav1.3 channels, another L-type subtype, are primarily expressed in the SA and AV nodes, where they contribute to pacemaker activity and atrial excitation-contraction coupling [53,54]. These channels are critical for diastolic depolarization, a process essential for maintaining automaticity in pacemaker cells [54,55]. In contrast, Cav3.1, a T-type Ca²⁺ channel, operates at lower voltages, facilitating Ca²⁺ influx during small depolarizations and playing a key role in initiating pacemaker activity under certain physiological conditions [56,57]. Both Cav1.3 and Cav3.1 are co-expressed in the SA and AV nodes, where their synergistic activity ensures proper impulse formation and conduction [57,58]. Genetic ablation of these channels disrupts cardiac automaticity, underscoring their importance in maintaining rhythm [57,59].

Clinical consequences of Ca²⁺ dysregulation are evident in conditions such as hypercalcemia, characterized by elevated serum Ca²⁺ levels. Hypercalcemia is categorized into mild (< 12 mg/dL), moderate (12-14 mg/dL), and severe (> 14 mg/dL) levels, with distinct clinical manifestations [60,61]. Table 2 summarizes the severity levels and associated clinical outcomes. Mild hypercalcemia is often asymptomatic but may present with fatigue and constipation [61]. Moderate hypercalcemia can lead to cognitive dysfunction, nausea, and dehydration, while severe hypercalcemia is associated with life-threatening complications, including arrhythmias, coma, and cardiovascular collapse [60,61].

| Table 2: Severity Levels and Clinical Manifestations of Hypercalcemia. | ||

| Severity Level | Serum Ca²⁺ Level (mg/dL) | Clinical Manifestations |

| Mild | <12 | Often asymptomatic; may include fatigue, mild constipation |

| Moderate | 12–14 | Cognitive dysfunction, nausea, dehydration |

| Severe | >14 | Arrhythmias, coma, cardiovascular collapse |

Hypercalcemia adversely affects cardiac function by shortening the APD and increasing contractility, which can predispose the myocardium to arrhythmias and ischemic injury [22,23]. Elevated Ca²⁺ levels also disrupt intracellular Ca²⁺ homeostasis, exacerbating oxidative stress and impairing mitochondrial function, which may further destabilize cardiac electrophysiology [20,31]. Management strategies for hypercalcemia involve addressing the underlying cause, such as malignancy or hyperparathyroidism, while employing therapies like intravenous hydration, bisphosphonates, and calcitonin to reduce serum Ca²⁺ levels [22,60].

Ca²⁺ serves indispensable roles in both the electrical and mechanical aspects of cardiac function, with Cav1.2, Cav1.3, and Cav3.1 channels contributing to distinct yet interconnected processes. Dysregulation of Ca²⁺ homeostasis, particularly in the context of hypercalcemia, poses significant risks for cardiac health. Addressing Ca²⁺ imbalances through targeted therapeutic interventions is essential for improving patient outcomes in cardiac diseases.

K+’s role in cardiac electrophysiology

K⁺ plays a pivotal role in cardiac electrophysiology, influencing all phases of the cardiac action potential and maintaining the delicate balance required for normal cardiac rhythm. Its involvement spans the establishment of the resting membrane potential, the repolarization phases of the action potential, and the regulation of cardiac excitability and conduction [1,10,17]. The efflux of K⁺ ions during phase 3 of the cardiac action potential is critical for rapid repolarization, while IK1 stabilizes the resting membrane potential during phase 4 [1,11]. Furthermore, the transient outward K⁺ current Ito is essential during phase 1, contributing to early repolarization and ensuring the efficient propagation of electrical signals through the myocardium [11,12].

The equilibrium of extracellular K⁺ levels is essential to maintaining these physiological processes. Deviations, particularly hyperkalemia, significantly impact cardiac electrophysiology and predispose individuals to life-threatening arrhythmias. Hyperkalemia is clinically defined as a plasma K⁺ concentration exceeding 5.0 mmol/L and is stratified into mild (5.0–6.0 mmol/L), moderate (6.0–7.0 mmol/L), and severe (>7.0 mmol/L) categories, each associated with distinct ECG changes and arrhythmia risks [18,62]. Table 3 summarizes these severity classifications and corresponding ECG alterations.

| Table 3: Severity of Hyperkalemia and Associated ECG Changes. | ||

| Severity | K⁺ Range | ECG Changes |

| Mild Hyperkalemia | 5.0–6.0 mM | Peaked T waves, shortened QT interval |

| Moderate Hyperkalemia | 6.0–7.0 mM | Prolonged PR interval, widened QRS complex |

| Severe Hyperkalemia | >7.0 mM | Sine wave pattern, absent P waves |

| (Source: [18,62,63]) | ||

In mild hyperkalemia, the primary ECG manifestation is the appearance of peaked T waves, resulting from accelerated repolarization due to increased extracellular K⁺ concentrations [18]. These changes reflect enhanced K⁺ efflux during phase 3, which shortens the APD and reduces the QT interval [18,19]. Although these alterations may appear benign, they serve as early markers of K⁺ dysregulation requiring prompt attention [19].

As K⁺ levels progress into the moderate range (6.0–7.0 mmol/L), the ECG changes become more pronounced. The PR interval elongates, reflecting delayed Atrioventricular (AV) conduction, while the QRS complex widens due to slowed depolarization of ventricular myocytes [18]. These effects arise from K⁺-induced depolarization of the resting membrane potential, which inactivates Nav1.5 and reduces the availability of Na⁺ currents during phase 0 [1,10]. This impairment in conduction velocity predisposes patients to reentrant arrhythmias, including ventricular tachycardia and fibrillation [19,64].

In severe hyperkalemia (> 7.0 mmol/L), the ECG trace displays a sine wave pattern characterized by extreme QRS widening and the loss of P waves, signifying near-complete atrial conduction block [18,63]. These changes reflect the profound depolarization of cardiac myocytes, which compromises their excitability and synchronization [19]. Without immediate intervention, such as the administration of Ca²⁺ gluconate to stabilize cardiac membranes, these patients are at high risk for asystole or ventricular fibrillation [65,66].

The arrhythmogenic potential of hyperkalemia is primarily attributed to its effects on myocardial depolarization and repolarization. Elevated extracellular K⁺ levels reduce the electrochemical gradient for K⁺ efflux, leading to depolarization of the resting membrane potential [1,10]. This depolarization inactivates Nav1.5, slowing conduction velocity and increasing the risk of reentrant arrhythmias [19]. Concurrently, the elevated K⁺ levels shorten the APD by enhancing K⁺ currents during phase 3, thereby increasing dispersion of repolarization and susceptibility to ventricular fibrillation [35].

Clinical data underscore the prevalence and severity of hyperkalemia in specific populations, particularly those with Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD), HF, or those receiving K⁺-retaining medications. Patients with CKD are particularly vulnerable due to impaired renal excretion of K⁺, leading to chronic hyperkalemia and an elevated risk of sudden cardiac death [67,68]. Medications such as renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors exacerbate this risk by further reducing renal K⁺ clearance [68].

Despite its potential lethality, hyperkalemia often presents diagnostic challenges because ECG changes are not always specific or present in the early stages [67]. Therefore, continuous cardiac monitoring and serial laboratory testing are essential for patients at risk of rapid K⁺ fluctuations, particularly in critical care settings [67,69].

Management strategies for hyperkalemia aim to stabilize the cardiac membrane, shift K⁺ intracellularly, and enhance K⁺ excretion. The administration of Ca²⁺ gluconate is a cornerstone therapy for stabilizing myocardial excitability in severe cases [65,66]. Insulin, often co-administered with glucose, promotes intracellular K⁺ uptake by activating the Na⁺/K⁺-ATPase pump [70]. Beta-agonists, such as albuterol, provide a complementary mechanism to drive K⁺ intracellularly [65]. In refractory cases or in patients with CKD, definitive treatment with dialysis may be required to remove excess K⁺ from the bloodstream [70].

K⁺ is indispensable for cardiac electrophysiology, yet its dysregulation, particularly in the form of hyperkalemia, poses significant risks to cardiac rhythm and function. The severity of hyperkalemia correlates with specific ECG changes and escalating arrhythmia risks, necessitating prompt recognition and management. As research continues to elucidate the molecular underpinnings of K⁺’s role in cardiac electrophysiology, targeted therapies may emerge to better address the challenges posed by this critical electrolyte imbalance.

Mg²+’s role in cardiac electrophysiology

Mg²⁺ plays an essential role in cardiac electrophysiology by stabilizing cellular membranes and modulating ion channel activity, which are critical for maintaining normal cardiac excitability and rhythm [25,71]. Its primary function involves regulating the activity of various ion channels, including K⁺ and Ca²⁺ channels, as well as the Na⁺/K⁺ ATPase pump, which collectively influence cardiac action potentials and muscle contraction [24,71]. Mg²⁺’s ability to stabilize resting membrane potential is vital for preventing arrhythmias and ensuring the proper timing of cardiac cycles [25].

In particular, Mg²⁺ modulates Cav1.2, which are responsible for the plateau phase (Phase 2) of the cardiac action potential [1,52]. By competing with Ca²⁺ ions during their entry through Cav1.2 channels, Mg²⁺ decreases Ca²⁺ influx, thus affecting both contractility and electrical excitability of the myocardium [52,71]. This Mg²⁺-mediated regulation ensures the proper termination of Ca²⁺ influx, maintaining APD and preventing Ca²⁺ overload, which can otherwise predispose to arrhythmias [25,71].

Mg²⁺ also modulates K⁺ currents, including IK1, IKr and IKs, which are crucial for repolarization during Phase 3 of the cardiac action potential [24,71]. By promoting K⁺ channel functionality, Mg²⁺ plays a protective role against arrhythmias like torsades de pointes, which are linked to prolonged APD [36,72].

Electrolyte disturbances involving Mg²⁺, such as hypomagnesemia, are clinically significant predictors of cardiac events. Hypomagnesemia exacerbates oxidative stress and inflammation, further impairing ion channel function and cardiac electrophysiology [25,71]. In patients with acute myocardial infarction, low Mg²⁺ levels are strongly associated with arrhythmia risk, underscoring the importance of Mg²⁺ in cardiac health [26,73].

Overall, Mg²⁺’s intricate role in modulating ion channels and stabilizing cardiac membranes makes it indispensable for preserving cardiac rhythm and protecting against arrhythmogenic conditions [25,71].

Cl-’s role in cardiac electrophysiology

Cl⁻ channels play a pivotal role in maintaining the electrical stability and ionic homeostasis of cardiac cells, contributing significantly to the generation and modulation of cardiac action potentials and the regulation of cell volume [13,28,74]. These channels, which include CFTR, members of the ClC family, and TMEM16/anoctamin channels, fulfill diverse physiological roles in cardiac function [29,75,76] (Table 4).

| : Key Cl- Channels in Cardiac Function. | |||

| Channel | Role in Cardiac Function | Regulatory Factors | Clinical Implications |

| CFTR | Shortens APD | cAMP, protein kinase A | Altered electrophysiology in cystic fibrosis [75,78] |

| ClC-2, ClC-3 | Stabilizes membrane potential; regulates cell volume | Intracellular Cl- concentration | Arrhythmias, myocardial hypertrophy [28,74] |

| TMEM16A | Contributes to repolarization; prevents delayed afterdepolarizations | Ca²⁺, PIP2 | Ca²⁺-overloaded arrhythmias [29,76] |

CFTR channels, primarily regulated by cyclic AMP (cAMP) and protein kinase A, play a crucial role in phase 3 repolarization by counteracting the prolongation effects of enhanced Ca²⁺ channel currents, which shortens the APD [75,77]. This modulation helps prevent early afterdepolarizations and triggered activities, reducing the arrhythmogenic potential of cardiac cells [76]. Dysfunction in CFTR channels, as seen in patients with cystic fibrosis, has been associated with altered cardiac electrophysiology, underscoring their importance in maintaining normal cardiac function [75,78].

The ClC family, particularly ClC-2 and ClC-3 Cl- channels, contributes to cardiac electrophysiology by regulating cell volume and intracellular Cl⁻ concentration [28,29]. These channels influence the resting membrane potential and repolarization rate, which are critical for maintaining cardiac rhythm and preventing arrhythmias [29,30]. For example, ClC-2 channels are involved in the stabilization of atrial and ventricular myocytes, while ClC-3 channels play a role in the dynamic regulation of cell excitability during stress conditions [28,74].

TMEM16 channels, also known as anoctamin channels, are Ca²⁺-activated Cl⁻ channels that contribute to the transient outward current during action potential repolarization [29,76]. Their involvement in Mg²⁺-overloaded cells suggests their involvement in arrhythmogenic delayed after depolarizations [29,76]. TMEM16A channels, in particular, are regulated by phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) and intracellular Mg²⁺ levels, which regulate their gating dynamics and electrophysiological properties [79,80]. Dysregulation of these channels may lead to abnormal Cl- conductance, resulting in prolonged APD and increased susceptibility to arrhythmias [28,30].

Clinically, Cl⁻ channel dysfunctions are implicated in several cardiac pathologies, including myocardial hypertrophy, HF, and arrhythmias [29,74]. The modulation of Cl⁻ channels presents promising therapeutic targets for arrhythmia management and cardiac remodeling [30,75]. For instance, targeting CFTR channels may offer novel strategies to counteract arrhythmogenic effects and improve cardiac contractility in patients with cystic fibrosis [74,78]. Additionally, experimental evidence supports the role of ClC and TMEM16 channels in maintaining cardiac rhythm and excitability, highlighting their potential as precision medicine targets for arrhythmia prevention [28,29].

Cl⁻ channels serve indispensable roles in cardiac electrophysiology, linking ionic regulation to heart function and pathology. Their diverse contributions, coupled with emerging therapeutic insights, underscore the importance of continued research into their mechanisms and clinical applications.

Acid-base imbalances and cardiac electrolyte homeostasis

Acid-base disturbances, such as acidosis and alkalosis, significantly alter the serum and intracellular concentrations of key electrolytes, including Na⁺, K⁺, and Ca²⁺, which are critical for cardiac electrophysiology and function [81,82]. In conditions of acidosis, the increased concentration of hydrogen ions (H⁺) leads to a cellular exchange where H⁺ ions enter cells in exchange for K⁺ ions, thereby resulting in hyperkalemia [81,82]. Elevated extracellular K⁺ levels in acidosis can destabilize cardiac conduction and increase the risk of arrhythmias [81,83]. Conversely, alkalosis results in a reduction of extracellular H⁺ ions, prompting H⁺ ions to exit cells in exchange for K⁺, which drives K⁺ intracellularly and results in hypokalemia [81,82]. This state predisposes the heart to increased irritability and arrhythmogenesis [82,84].

Acidosis also influences Na⁺ levels by contributing to dilutional hyponatremia or impairing renal Na⁺ handling [82,85]. In parallel, alkalosis can cause hypernatremia due to enhanced renal water excretion relative to Na⁺ [85]. Furthermore, acidosis increases ionized Ca²⁺ levels by reducing protein binding, which can exacerbate arrhythmias, whereas alkalosis decreases ionized Ca²⁺, leading to neuromuscular excitability and potential cardiac instability [81,84]. These shifts are particularly critical in critically ill patients where electrolyte imbalances are prevalent, necessitating careful monitoring and correction to prevent complications such as seizures and arrhythmias [69,86].

Na+ channels

Nav1.5 are integral membrane proteins essential for the initiation and propagation of action potentials in excitable tissues, including cardiac myocytes [87]. Structurally, these channels comprise a large alpha subunit, which forms the ion-conducting pore, and auxiliary beta subunits that modulate the gating kinetics and surface expression of the channel [15,87]. The alpha subunit consists of four homologous domains (DI–DIV), each containing six transmembrane segments (S1–S6), with the S4 helix acting as the voltage sensor and S5–S6 forming the ion-selective pore [87]. These structural components allow the channel to transition between closed, open, and inactivated states in response to changes in membrane potential [15]. Na⁺ channels are primarily responsible for the rapid depolarization phase (Phase 0) of the cardiac action potential, a critical event for the efficient propagation of electrical impulses across the myocardium [1,10].

The function of Na⁺ channels is tightly regulated by extracellular and intracellular electrolytes. Na⁺ ions Na⁺ themselves are the primary charge carriers through these channels, driving the rapid influx that initiates the action potential [14,87]. Ca²⁺ and Mg²⁺ also modulate channel function by influencing their gating properties. External Ca²⁺ ions alter the voltage dependence of activation and inactivation, stabilizing the closed state to prevent excessive excitability [15,87]. Similarly, Mg²⁺ competes with Na⁺ for binding sites within the channel, limiting Na⁺ influx during action potential generation [15,87]. This fine-tuned regulation by divalent cations ensures proper electrical signaling and minimizes the risk of arrhythmias [87].

Pathophysiological conditions, such as electrolyte imbalances, disrupt Na⁺ channel function. Hypernatremia, characterized by elevated extracellular Na⁺ levels, enhances Na⁺ influx, potentially leading to increased conduction velocity and arrhythmic risk [43]. Conversely, hyponatremia, associated with reduced Na⁺ levels, diminishes depolarization efficiency, impairing action potential propagation and contributing to arrhythmic conditions [41]. Dysfunctional regulation of Na⁺ channels underlies various cardiac arrhythmias and diseases, emphasizing their central role in cardiac electrophysiology [14,15,87].

Ca²⁺ channels: Cav1.2 channels serve as the primary contributors to Ca²⁺ influx during the plateau phase (Phase 2) of the cardiac action potential, maintaining a prolonged depolarization necessary for effective myocardial contraction [1,10]. This process is critical for CICR, whereby the initial influx of Ca²⁺ through Cav1.2 channels triggers the release of stored Ca²⁺ from the sarcoplasmic reticulum, amplifying intracellular Ca²⁺ levels and ensuring robust excitation-contraction coupling [20,21]. Dysregulation of Cav1.2 channel activity, particularly through phosphorylation at sites such as Thr1604, has been implicated in pathological myocardial hypertrophy, further emphasizing their importance in cardiac health [52].

Cav1.3 channels, while less widely distributed than Cav1.2, are predominantly expressed in pacemaker cells such as those in the SAN and AV nodes [86]. These channels contribute to pacemaker activity by regulating Ca²⁺ influx during diastolic depolarization, a phase critical for initiating subsequent action potentials in nodal cells [53,54]. Cav1.3 channels also mediate β-adrenergic stimulation-induced automaticity in dormant SAN pacemaker cells, linking autonomic nervous system activity to heart rate modulation [54]. Additionally, Cav1.3 channels are involved in generating persistent Na⁺ currents, further supporting diastolic depolarization and automaticity in pacemaker cells [55].

Cav3.1 channels, categorized as T-type Ca²⁺ channels, activate at lower voltages compared to their L-type counterparts, making them essential for pacemaker activity during small depolarizations [56]. These channels are co-expressed with Cav1.3 in the SAN and AV nodes, where their joint activity is necessary for impulse formation and conduction [57]. Genetic ablation of Cav3.1 disrupts heart automaticity, demonstrating their integral role in maintaining rhythmic cardiac impulses [57,58].

Channelopathies affecting Cav1.2, Cav1.3, and Cav3.1 Mg²⁺ channels have been linked to various arrhythmogenic conditions, including sinus node dysfunction and heart block [58,59]. For example, mutations in Cav1.3 have been implicated in sick sinus syndrome, highlighting the importance of these channels in maintaining cardiac rhythm [59]. Therapeutic targeting of Ca²⁺ channels, such as the use of Ca²⁺ channel blockers, offers promising avenues for managing arrhythmias and conditions like myocardial hypertrophy [20,34].

Ca²⁺ channels are central to cardiac electrophysiology, with distinct roles in excitation-contraction coupling, pacemaker activity, and impulse conduction. Further research into their molecular mechanisms and therapeutic modulation may provide new strategies for treating arrhythmias and other cardiac disorders.

K⁺ channels: K⁺ channels play an essential role in maintaining cardiac rhythm by regulating the repolarization phases of the cardiac action potential. Among the many K⁺ channels involved, the Kv11.1 (hERG), Kv7.1 (IKs), and inward rectifier potassium (Kir) channels stand out for their critical contributions to cardiac electrophysiology and their susceptibility to modulation by various factors, including polyamines, phospholipids, protons, and medications.

Kv11.1 (hERG) and Kv7.1 IKs channels

The Kv11.1 channel, encoded by the KCNH2 gene, generates the IKr, which is essential for the rapid repolarization during phase 3 of the cardiac action potential [89,90]. This current ensures timely repolarization of cardiac cells and prevents excessive prolongation of the action potential. Dysfunction of Kv11.1 is directly implicated in long QT syndrome, a condition that predisposes to torsades de pointes and sudden cardiac death [89,90]. Conversely, Kv7.1, encoded by the KCNQ1 gene, contributes to IKs, which plays a crucial role in maintaining action potential stability under conditions of heightened sympathetic activity [91,92]. IKs acts as a backup mechanism, complementing IKr during repolarization and enhancing electrical stability during sympathetic activation [90,93].

Kv7.1 channels are modulated by auxiliary subunits such as KCNE1, which alter channel kinetics and voltage dependence, further fine-tuning their contribution to cardiac repolarization [92]. Dysregulation of either Kv11.1 or Kv7.1 channels, due to genetic mutations or adverse drug interactions, can severely compromise cardiac rhythm, underscoring their critical importance in preventing arrhythmias [90,93].

Kir channels

Kir channels are crucial for stabilizing the resting membrane potential and facilitating phase 3 repolarization in cardiac cells [94]. Among them, Kir2.1 channels, encoded by the KCNJ2 gene, are particularly prominent. They mediate the IK1, which maintains the negative resting membrane potential and contributes to late-phase repolarization [94,95]. The unique rectification property of Kir channels arises from their voltage-dependent blockage by intracellular polyamines and Mg²⁺ ions, which limit outward K⁺ flow at depolarized potentials [95,96].

Modulation of Kir channels

Polyamines: Polyamines, such as spermine and spermidine, serve as key regulators of Kir channel activity by blocking the channel pore in a voltage-dependent manner [95,96]. These molecules interact with specific sites within the inner cavity and selectivity filter of Kir channels, with spermine exhibiting stronger blocking efficacy due to its larger size and higher charge density [95]. Disruption of polyamine binding, as seen in KCNJ2 mutations associated with Andersen-Tawil syndrome, impairs inward rectification, leading to arrhythmogenic phenotypes [94,97].

Phospholipids: Phosphoinositides, particularly phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2), are critical lipid regulators of Kir channels. PIP2 binds to specific residues on Kir channels, stabilizing their open state and enhancing channel activity [98,99]. Mutations that alter PIP2 binding, such as E179K in Kir6.2, increase PIP2 affinity and channel activity, whereas mutations like K67N reduce PIP2 binding, leading to decreased channel function [98]. Interactions with structural proteins such as caveolin-3 further modulate Kir2.x channel trafficking and surface expression, with mutations in caveolin-3 linked to Purkinje cell-dependent ventricular arrhythmias [100].

Protons: Changes in intracellular pH also modulate Kir channel activity. Acidosis, a condition often encountered during ischemia, reduces PIP2 binding and alters channel gating, thereby decreasing IK1 and prolonging APD [94,98]. Conversely, alkalosis enhances Kir channel activity, shortening the action potential and reducing cellular excitability [94]. Mutations that alter channel sensitivity to protons can exacerbate arrhythmia susceptibility [97].

Medications: Certain medications, including antiarrhythmic drugs, can also impact Kir channel function. Class-Ic drugs like flecainide and propafenone increase the risk of proarrhythmia in patients with KCNJ2 mutations by altering Kir channel gating and promoting ventricular arrhythmias [101]. Furthermore, medications such as quinidine can modulate channel trafficking by inducing internalization, thereby reducing Kir channel density and exacerbating arrhythmogenic risk [102].

These effects on Kir channels are summarized in Table 5.

| Table 5: Regulation of Kir Channels and Arrhythmogenesis. | ||

| Factor | Mechanism/Effect | References |

| Polyamines | Voltage-dependent blockage causing inward rectification | [95,96] |

| Phospholipids | PIP2 binding stabilizes open state and enhances activity | [98] |

| Protons | Acidosis reduces PIP2 binding and channel activity | [98] |

| Medications | Class-Ic drugs increase proarrhythmia risk in mutants | [104] |

Cl- channels

Cl⁻ channels are essential regulators of cardiac electrophysiology, contributing significantly to the maintenance of electrical stability, action potential dynamics, and overall cardiac function [13]. These channels play a pivotal role in setting the resting membrane potential, regulating APD, and influencing the repolarization process, particularly during phases 1 and 3 of the cardiac action potential [28,29]. The CFTR channel, a cAMP-dependent Cl⁻ channel, modulates APD by counteracting prolonged depolarization caused by enhanced Ca²⁺ currents, thereby facilitating phase 3 repolarization [75,77]. Increased Cl⁻ conductance through CFTR can prevent early afterdepolarizations, reducing arrhythmogenic potential [76]. Conversely, impaired Cl⁻ conductance may prolong APD, predisposing the heart to arrhythmias [29,30].

Other Cl⁻ channels, such as members of the ClC family (e.g., ClC-2 and ClC-3), contribute to volume regulation and influence the resting membrane potential and repolarization rate in both atrial and ventricular myocytes [28]. TMEM16/anoctamin channels, which are Ca²⁺-activated Cl⁻ channels, mediate transient outward currents, aiding in action potential repolarization and potentially contributing to delayed afterdepolarizations in Ca²⁺-overloaded cells [28,76]. Dysfunctions in Cl⁻ channels, such as CFTR mutations observed in cystic fibrosis, are associated with altered electrophysiology and increased susceptibility to arrhythmias [75,78].

Clinical evidence underscores the role of Cl⁻ channels in arrhythmogenesis, myocardial hypertrophy, and HF, highlighting their therapeutic potential [30,74]. Modulating Cl⁻ channel activity could offer novel approaches for treating arrhythmias and remodeling-associated cardiac pathologies [28,29].

HCN channels

HCN channels are essential for cardiac pacemaking, particularly in the SAN, which serves as the heart’s primary pacemaker [103]. These channels generate the “funny current” If, a mixed inward flow of Na⁺ and K⁺ ions, which activates during hyperpolarization and gradually depolarizes SAN cells to initiate action potentials [39,104]. HCN channels are modulated by cyclic nucleotides such as cAMP and cGMP, linking their activity to autonomic nervous system regulation of heart rate [38].

Electrolytes play a critical role in regulating HCN channels. K⁺ levels influence the membrane potential, affecting channel activation and gating [39]. Similarly, Na⁺ directly contributes to the ionic composition of the If current, while variations in Ca²⁺ modulate HCN activity via Ca²⁺-activated signaling pathways [104,105]. Mg²⁺ also facilitates channel gating by stabilizing protein linkages, enhancing sensitivity to cyclic nucleotides [103,105]. Dysregulation of these electrolytes, such as hyperkalemia or hypokalemia, can impair pacemaking, leading to arrhythmias [104]. These findings underscore the importance of electrolyte balance for optimal HCN function and cardiac rhythm stability [40,106].

Beyond genetic and molecular factors, external conditions such as pH and pollutants can drastically perturb electrolyte balance and cardiac rhythm.

Impact of air pollution on electrolyte homeostasis, ion channel activity, and cardiac electrophysiology

Air pollution has emerged as a critical environmental risk factor affecting cardiovascular health, contributing to disruptions in electrolyte homeostasis, ion channel activity, and cardiac electrophysiology [8,9]. Exposure to air pollutants, particularly fine particulate matter (PM2.5), NO2, and Ozone (O3), is strongly associated with an increased incidence of cardiac arrhythmias, abnormal ion channel functioning, and systemic inflammation, all of which exacerbate electrophysiological dysfunction [107].

Effects on cardiac electrophysiology

Air pollution-induced arrhythmias, including atrial and ventricular arrhythmias, are a key manifestation of its impact on cardiac electrophysiology [8,108]. A 10 μg/m³ increase in PM2.5 concentration, for instance, has been associated with a 2% increase in Premature Ventricular Contraction (PVC) counts within two hours of exposure [110,111]. Similarly, short-term exposure to PM10 and NO₂ has been shown to trigger ventricular tachyarrhythmias in patients with implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs) [105,108]. These findings underscore the vulnerability of individuals with underlying cardiovascular conditions to pollution-related cardiac events [107].

Air pollution also induces significant alterations in cardiac repolarization, a phase essential for the cardiac action potential [107]. Prolonged QT duration, increased T-wave complexity, and elevated variability in T-wave morphology have been observed following PM2.5 exposure, reflecting myocardial substrate changes that heighten arrhythmogenic risk [107]. Increases in spatial dispersion of repolarization, driven by combined exposure to Concentrated Ambient Particles (CAP) and ozone, further amplify the susceptibility to arrhythmias.

Disruption of ion channel activity

The electrophysiological effects of air pollution are largely mediated through direct modulation of ion channel activity. Particulate matter and gaseous pollutants alter the function of voltage-gated Na⁺, K⁺, and Ca²⁺ channels, resulting in abnormal APD’s and electrical instability in cardiomyocytes [9]. For instance, PM2.5 exposure has been linked to increased dispersion of repolarization, a hallmark of arrhythmogenesis, by modulating the activity of these ion channels [8].

Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS), generated as a consequence of pollutant exposure, play a central role in altering ion channel function [9]. ROS oxidize ion channels, disrupting their gating mechanisms and impairing their ability to regulate ionic fluxes [9,107]. Furthermore, oxidative stress activates intracellular signaling pathways that exacerbate inflammation and electrophysiological dysfunction, compounding the adverse effects of air pollution on cardiac cells [9].

Effects on electrolyte homeostasis

The disruption of ion channel function by air pollution is closely linked to imbalances in electrolyte homeostasis, which significantly impact cardiac electrophysiology [8]. Particulates and gaseous pollutants interfere with the movement of key electrolytes, such as Na⁺, K⁺, and Ca²⁺, across cellular membranes, affecting the ionic gradients that drive cardiac action potentials [9].

For example, ROS generated by pollution exposure disrupt the activity of the Na⁺/K⁺ pump and Na⁺/Ca²⁺ exchanger, which are critical for maintaining ionic equilibrium in cardiac cells. Dysregulation of these transporters alters cytosolic concentrations of Na⁺ and Ca²⁺, impairing the pacemaker activity of SAN cells and increasing the risk of arrhythmias. Additionally, changes in extracellular K⁺ levels due to pollutant exposure can affect the resting membrane potential, further destabilizing cardiac rhythm [8,109].

Role of systemic inflammation and autonomic nervous system modulation

Beyond direct effects on ion channel activity and electrolyte balance, air pollution indirectly impacts cardiac electrophysiology through systemic inflammation and autonomic nervous system dysregulation [9]. Pulmonary inflammation triggered by pollutant inhalation leads to the release of inflammatory mediators and ROS into the bloodstream, which subsequently act on the cardiovascular system [9]. These mediators contribute to endothelial dysfunction, increased vascular resistance, and altered cardiac electrophysiological properties.

Furthermore, pollution exposure is associated with increased sympathetic tone and reduced parasympathetic activity, as evidenced by changes in heart rate variability. Elevated low-frequency to high-frequency (LF/HF) ratios, indicative of autonomic imbalance, have been linked to increased spatial dispersion of repolarization and heightened arrhythmogenic risk [107].

Clinical implications and vulnerable populations

The clinical implications of air pollution-induced disruptions in electrolyte homeostasis, ion channel activity, and cardiac electrophysiology are profound, particularly for individuals with preexisting cardiovascular conditions [107]. Patients with ischemic heart disease, HF, or arrhythmias are especially vulnerable to the compounded effects of pollution exposure, which can exacerbate repolarization abnormalities and increase the risk of life-threatening arrhythmias [107,108].

Efforts to mitigate the cardiovascular impact of air pollution should focus on reducing exposure, particularly in high-risk populations, and addressing the underlying mechanisms of oxidative stress and ion channel dysfunction [9]. Pharmacological interventions targeting ROS generation and autonomic dysregulation, as well as therapies aimed at stabilizing electrolyte homeostasis, may hold promise for reducing pollution-related cardiac morbidity and mortality [9,104].

Electrolytes and their roles in myocardial ultrastructure, mitochondrial function, cardiac fibrosis/remodeling, and disease correlations

Electrolytes are essential for maintaining the ultrastructural integrity and functional capacity of myocardial cells, influencing key cellular components such as sarcomeres, mitochondria, and the Extracellular Matrix (ECM). Disturbances in electrolyte levels can profoundly alter cardiac structure and function, contributing to pathological remodeling, fibrosis, and the development of cardiomyopathies. This section explores the mechanistic roles of electrolytes—namely Ca²⁺, K⁺, Na⁺, Mg²⁺, and Cl⁻—in maintaining cardiac ultrastructure and their implications for disease progression.

Myocardial cell ultrastructure: sarcomeres, T-tubules, and intercalated discs

The ultrastructure of myocardial cells is characterized by sarcomeres, T-tubules, and intercalated discs, all of which are crucial for synchronized cardiac contraction. Sarcomeres are the fundamental contractile units, dependent on Ca²⁺ for activation of the actin-myosin interaction that drives muscle contraction [31]. Ca²⁺ binds to troponin, enabling the sliding of actin and myosin filaments, a process that is tightly regulated by intracellular Ca²⁺ concentrations and the sarcoplasmic reticulum [51]. T-tubules facilitate the propagation of action potentials into the deeper regions of the cardiomyocyte, ensuring uniform Ca²⁺ release and contraction [112]. Na⁺ and K⁺ gradients across the sarcolemma, maintained by the Na⁺/K⁺ ATPase pump, are essential for generating and propagating action potentials that activate the T-tubules [71,109].

Intercalated discs, composed of gap junctions and desmosomes, enable electrical and mechanical coupling between adjacent myocardial cells [31]. These structures rely on the surrounding ionic environment for efficient electrical signal transmission. For example, K⁺ plays a vital role in maintaining the resting membrane potential necessary for action potential initiation and synchronization across the myocardium [37]. Dysregulation of these ion gradients can impair intercellular communication, leading to arrhythmias and contractile dysfunction [31,51].

Mitochondrial function and electrolyte regulation

Mitochondria are central to energy production in cardiomyocytes and are highly sensitive to changes in electrolyte concentrations. Ca²⁺ plays a dual role in mitochondrial function, acting as a signal for ATP production while also posing a risk of mitochondrial dysfunction when dysregulated [31,71]. Under physiological conditions, Ca²⁺ enters the mitochondria via the Mitochondrial Ca²⁺ Uniporter (MCU) to stimulate ATP synthesis. However, excessive Ca²⁺ influx, often resulting from hypercalcemia, can lead to mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP) opening, reduced ATP production, and the initiation of apoptotic pathways [22]. This disruption is a key mechanism in cardiac ischemia-reperfusion injury and HF [31].

K⁺ also influences mitochondrial function by maintaining the electrochemical gradient across the inner mitochondrial membrane, which is critical for ATP synthesis [113]. Hypokalemia can disrupt mitochondrial membrane potential, impairing energy production and increasing oxidative stress [31]. Similarly, Mg²⁺ regulates mitochondrial ATP production by modulating ATP synthase activity and stabilizing the mitochondrial membrane potential [25,71]. Mg²⁺ deficiencies have been shown to impair mitochondrial function, contributing to energy deficits and oxidative stress in cardiac cells [71].

Electrolytes in cardiac fibrosis and remodeling

Fibrosis results from excessive deposition of ECM components, such as collagen, which disrupts normal myocardial architecture and impairs cardiac function [114]. Ca²⁺ dysregulation promotes fibroblast activation and myofibroblast differentiation, key processes in ECM remodeling [22]. Elevated intracellular Ca²⁺ levels increase the activity of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), enzymes that degrade ECM components, and their tissue inhibitors (TIMPs), leading to pathological ECM remodeling [114].

Mg²⁺, on the other hand, has an inhibitory effect on fibroblast proliferation and ECM deposition. Mg²⁺ deficiency can exacerbate fibrosis by enhancing oxidative stress and inflammation, both of which activate fibroblasts and promote collagen synthesis [71]. This underscores the critical role of maintaining Mg²⁺ homeostasis in preventing fibrotic remodeling and preserving myocardial compliance [25].

K⁺ and Cl⁻ also modulate fibrosis through their roles in cellular signaling and volume regulation. K⁺ efflux is essential for the activation of caspases and apoptosis, processes that can limit fibroblast proliferation under pathological conditions [113]. Cl⁻ channels, such as the CFTR, contribute to cell volume regulation and signaling pathways that influence fibroblast activity [13]. Dysregulation of these electrolytes can lead to abnormal ECM deposition and increased myocardial stiffness, contributing to diastolic dysfunction [75].

Disease correlations: Cardiomyopathies and electrolyte imbalances

Hypokalemia and hyperkalemia are well-documented contributors to arrhythmogenic conditions that exacerbate underlying cardiomyopathies [37,113]. Hypokalemia prolongs the APD by reducing the activity of delayed rectifier K⁺ currents, increasing the risk of early afterdepolarizations and torsades de pointes arrhythmias [35]. Conversely, hyperkalemia depolarizes the resting membrane potential, reducing excitability and conduction velocity, which can lead to life-threatening arrhythmias such as ventricular fibrillation [18,19].

Ca²⁺ imbalances also play a pivotal role in cardio-myopathies by disrupting excitation-contraction coupling. Hypercalcemia shortens the APD, increasing contractility but also predisposing the heart to arrhythmias and hypertrophy [22]. Hypocalcemia, on the other hand, prolongs the action potential and reduces myocardial contractility, leading to HF and arrhythmias [22,31]. Mg²⁺ deficiencies further exacerbate these conditions by impairing Ca²⁺ handling and increasing oxidative stress [25,31].

Moreover, electrolyte disturbances influence myocardial energy metabolism and oxidative stress pathways, both of which are critical in the progression of cardiomyopathies. Mg²⁺ deficiency impairs mitochondrial ATP production, leading to energy deficits that exacerbate cardiac dysfunction [71]. Similarly, Ca²⁺ overload in mitochondria can trigger oxidative stress and apoptosis, contributing to myocardial fibrosis and HF [31].

Electrolyte-driven remodeling processes are particularly pronounced in conditions such as hypertension and diabetes, where chronic imbalances accelerate myocardial fibrosis and ECM remodeling [114]. For example, hypernatremia associated with primary hyperaldosteronism can increase myocardial stiffness and promote hypertrophy, worsening diastolic dysfunction and HF [42]. These findings highlight the intricate interplay between electrolyte homeostasis and the structural and functional integrity of the myocardium.

Implications for therapeutic interventions

Given the critical roles of electrolytes in cardiac ultrastructure, mitochondrial function, and ECM remodeling, therapeutic strategies aimed at restoring electrolyte balance hold significant promise in managing cardiomyopathies and preventing disease progression. Targeted interventions, such as K⁺ and Mg²⁺ supplementation, have shown efficacy in reducing arrhythmias and improving myocardial function [27,115]. Emerging therapies focusing on ion channel modulation and oxidative stress reduction further underscore the potential of electrolyte-targeted approaches in cardiac care [34].

Electrolytes, including Na⁺, K⁺, Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, and Cl-, are indispensable for the maintenance of cardiac electrophysiology, with their imbalances profoundly influencing cardiovascular outcomes. Variations in serum levels of these electrolytes are associated with arrhythmias, cardiomyopathies, and other cardiac dysfunctions, emphasizing their clinical relevance in cardiac management. This section summarizes key clinical findings regarding electrolyte disturbances, their cardiovascular implications, therapeutic strategies, and future research directions.

Electrolyte disturbances and cardiovascular outcomes

Hyponatremia, defined as serum Na⁺ below 135 mEq/L, is the most common electrolyte disorder in hospitalized patients and predicts poor outcomes in acute kidney injury, a condition that further complicates cardiac function [49,50]. In patients with atrial fibrillation without HF, hyponatremia has been associated with increased all-cause mortality within 365 days post-discharge, underscoring its significant impact on cardiac health [50]. Conversely, hypernatremia, defined as serum Na⁺ exceeding

145 mEq/L, is linked to adverse cardiovascular outcomes, including increased blood pressure and mortality in patients with Cardiovascular Disease (CVD) [44,45]. Hypernatremia is particularly prevalent in Intensive Care Units (ICUs), with a strong correlation to longer hospital stays and higher in-hospital mortality rates, especially in mechanically ventilated patients [46].

K⁺ imbalances, including hyperkalemia (serum K⁺ > 5.0 mmol/L) and hypokalemia (< 3.5 mmol/L), significantly impact cardiac electrophysiology and predispose patients to life-threatening arrhythmias. Hyperkalemia decreases the resting membrane potential, leading to slowed conduction and reduced excitability, while hypokalemia increases susceptibility to ventricular arrhythmias by prolonging APD [62,116]. Hypokalemia has been identified as a major risk factor for AF and prolonged QT intervals, especially in patients with inherited salt-losing tubulopathy, further highlighting its clinical significance [117]. Both hyperkalemia and hypokalemia are associated with increased mortality risk in patients with AF, illustrating the critical need for maintaining K⁺ balance [47,50].

Ca²⁺ imbalances also exert profound effects on cardiac outcomes. Hypercalcemia shortens the and increases cardiac contractility, often leading to arrhythmias, while hypocalcemia prolongs the APD and reduces contractility, which can result in HF [22,23]. Elevated Ca²⁺ levels in AF patients have been associated with longer hospital stays, increased costs, and higher mortality rates, highlighting the systemic burden of this disturbance [33].

Mg²⁺, a critical cofactor for ion channels, influences cardiac rhythm by stabilizing cell membranes and modulating K⁺ and Ca²⁺ channels. Hypomagnesemia, defined as serum Mg²⁺ < 1.3 mEq/L, is prevalent in acute myocardial infarction (AMI) patients and predicts higher arrhythmia risk [26,73]. Lower Mg²⁺ levels are also linked to greater incidence of Major Adverse Cardiac Events (MACE), illustrating its prognostic significance [118]. Conversely, Mg²⁺ supplementation has shown protective effects by reducing postoperative AF and ventricular arrhythmias [27] (Table 6).

| Table 6: Clinical Studies of Electrolyte Imbalances and Cardiac Outcomes. | |||

| Electrolyte | Disturbance | Associated Outcomes | Reference |

| Na⁺ | Hyponatremia | Increased all-cause mortality in atrial fibrillation patients without HF. | [50] |

| Na⁺ | Hypernatremia | Higher intensive care unit mortality rates and prolonged hospital stays | [46] |

| K⁺ | Hyperkalemia | Ventricular arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death | [62] |

Current therapeutic strategies

Therapeutic interventions aimed at correcting electrolyte imbalances represent a cornerstone in the management of cardiac conditions. For Na⁺ disturbances, hypernatremia management involves careful correction of serum Na⁺ levels to mitigate risks of cerebral edema or hemorrhage, emphasizing the need to address underlying causes such as dehydration or renal dysfunction [43,44]. Hyponatremia correction focuses on improving Na⁺ balance while avoiding rapid shifts that could lead to osmotic demyelination [49].

K⁺ management is pivotal in preventing arrhythmias. In hyperkalemia, immediate treatments such as Ca²⁺ gluconate, insulin, and beta-agonists are employed to stabilize cardiac membranes and promote intracellular K⁺ uptake [65,66]. For hypokalemia, K⁺ supplementation is recommended to restore normal cardiac function and minimize arrhythmia risk [68]. Continuous cardiac monitoring is essential for patients at risk of rapid K⁺ fluctuations, as ECG changes may not always reflect the severity of dyskalemia [67].

Mg²⁺ supplementation is increasingly recognized for its role in arrhythmia prevention and control. Studies demonstrate that Mg²⁺ correction reduces ventricular ectopies and controls the ventricular response in AF [27,112,119-122]. However, larger clinical trials are needed to confirm the mortality benefits of Mg²⁺ therapy, as existing evidence remains inconsistent [115,123-137].

Future research directions

The complexity of electrolyte dynamics in cardiac care necessitates ongoing research to elucidate underlying mechanisms and optimize therapeutic approaches. One key research area involves exploring the molecular pathways through which electrolytes influence ion channels and myocardial ultrastructure. For instance, understanding the role of K⁺ channels in Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy could lead to targeted ion channel modulation therapies [92,96].

Precision medicine approaches tailored to individual electrolyte profiles are another promising avenue. Advances in wearable biosensors capable of continuous electrolyte monitoring could enable real-time adjustments to therapy, improving outcomes in patients with dynamic electrolyte fluctuations [112]. Additionally, exploring the interplay between systemic diseases like diabetes or hypertension and electrolyte disturbances may provide insights into the etiology and management of secondary cardiac complications [34].

Research into the long-term consequences of chronic electrolyte imbalances on myocardial remodeling and fibrosis could inform prevention strategies for cardiomyopathies. Electrolyte-driven alterations in the ECM, such as those mediated by Ca²⁺ and Mg²⁺, are implicated in cardiac fibrosis and hypertrophy, highlighting the need for further investigation [32,114].

The provided manuscript, “From Beat to Beat: How Electrolytes Shape the Heart’s Rhythmic Symphony and Structure,” thoroughly elucidates the pivotal roles of key electrolytes- Na⁺, K⁺, Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, and Cl⁻ - in maintaining cardiac electrophysiology and myocardial structure. These electrolytes shape the action potential phases, regulate cardiac muscle contraction, and ensure synchronized cardiac rhythm [1,10,112]. The manuscript emphasizes how imbalances, such as hyperkalemia, hypokalemia, hypernatremia, and hypocalcemia, directly contribute to arrhythmias and cardiomyopathies by altering the electrical and structural dynamics of the heart [50,116].

The cardiac action potential is dissected into five phases, with each phase governed by specific ionic movements. Na⁺ influx dominates Phase 0, initiating rapid depolarization [1,10]. K⁺ currents, including transient outward and delayed rectifier currents, are critical for repolarization during Phases 1 and 3 [11,17]. Ca²⁺ influx during Phase 2 facilitates excitation-contraction coupling, linking electrical activity to mechanical contraction [20]. Mg²⁺ stabilizes ion channel functions and modulates K⁺ and Ca²⁺ dynamics, highlighting its protective role against arrhythmias [25,71]. Cl⁻ ions also contribute significantly to action potential repolarization and cellular excitability [12,13].

Electrolyte-driven disturbances in myocardial ultrastructure further exacerbate cardiac dysfunction. Ca²⁺ dysregulation impairs sarcomere contraction and mitochondrial energetics, while K⁺ imbalances disrupt intercalated disc-mediated electrical signal propagation [31,33]. Prolonged electrolyte imbalances lead to ECM remodeling and fibrosis, which diminish cardiac compliance and elevate arrhythmia risks [32,114].

Future research should prioritize elucidating the molecular mechanisms underpinning electrolyte regulation of ion channels, particularly focusing on polyamines, phospholipids, and protons as modulators of Kir channels [94,95]. Advanced studies are also needed to explore how dynamic alterations in Cav1.3 and Cav3.1 Ca²⁺ channels contribute to pacemaker dysfunction and arrhythmogenesis [57,88]. Investigating the interplay between systemic diseases, such as diabetes and hypertension, and electrolyte imbalances could illuminate novel therapeutic targets [5,34].