More Information

Submitted: May 02, 2025 | Approved: May 09, 2025 | Published: May 12, 2025

How to cite this article: Muciño-Bermejo MJ. Extracorporeal Organ Support in Cardiorenal Syndrome. J Cardiol Cardiovasc Med. 2025; 10(3): 062-069. Available from: https://dx.doi.org/10.29328/journal.jccm.1001211

DOI: 10.29328/journal.jccm.1001211

Copyright license: © 2025 Muciño-Bermejo MJ. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Keywords: Cardiorenal syndrome; Heart failure; Acute kidney injury; Chronic kidney disease; Extracorporeal organ support; Renal replacement therapy; Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; Albumin dialysis; Kidney damage

Abbreviations: CRS: Cardiorenal Syndrome; AKI: Acute Kidney Injury; CKD: Chronic Kidney Disease; GFR: Glomerular Filtration Rate; SAKI: Subclinical AKI; AKD: Acute Kidney Disease; HF: Heart Failure; LV: Left Ventricle; LVEF: Left Ventricle Ejection Fraction; HFrEF: HF With Reduced Ejection Fraction; HFpEF: HF With Preserved Ejection Fraction; AHF: Acute Heart Failure; CHF: Chronic Heart Failure; ADHF: Acutely Decompensated Heart Failure; WRD: Worsening Renal Function; RV: Right Ventricle; Ang II: Angiotensin II; ET-1: Endothelin-1; AVP: Arginine Vasopressin; CVP: Central Venous Pressure; ESRD: End-Stage Renal Disease; TNF-a: Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha; IL: Interleukin; ECOS: Extracorporeal Organ Support; UF: Ultrafiltration; NT-proBNP: Pro-B-Type Natriuretic Peptide; HRS: Hepatorenal Syndrome; ECMO: Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation

Extracorporeal Organ Support in Cardiorenal Syndrome

Maria-Jimena Mucino-Bermejo1,2*

1The American British Cowdray Medical Center, Mexico City, Mexico

2International Renal Research Institute of Vicenza (IRRIV), Vicenza, Italy

*Address for Correspondence: Maria-Jimena Mucino-Bermejo, The American British Cowdray Medical Center, Mexico City, Mexico, International Renal Research Institute of Vicenza (IRRIV), Vicenza, Italy, Email: [email protected]

Introduction: The term “Cardiorenal Syndrome” [CRS] is widely used to make reference to the vast array of interrelated, bidirectional interactions between heart-kidney derangements.

Objective: In the present manuscript, a brief description of CRS-related operational definitions and physiopathological mechanisms will be made, in order to better describe the therapeutic benefits of the use of ECOS in CRS patients, including achieving euvolemic state via ultrafiltration, inflammatory pathways regulation via hemadsorption and ECMO-provided hemodynamic support.

Discussion: Even when there is a high heterogenicity among cardiorenal syndrome clinical scenarios, common physiopathological pathways have been described, including neurohormonal adaptations, and hemodynamic changes, right ventricle dysfunction, oxidative stress and proinflammatory pathways. Therapeutic benefits of the use of ECOS in CRS patients, include achieving euvolemic state via ultrafiltration, regulation of inflammatory pathways via hemoadsorption and ECMO-provided hemodynamic support.

Conclusion: Extracorporeal organ support represents a valuable therapeutic strategy for patients with cardiorenal syndrome. In the years to come, the potential of ECOS as an inflection point in the natural history of disease to prevent the development of organ failure, prevent single organ failure becoming a multiorgan failure, prevent chronic organ failure development and achieving full recovery will be among the most important subjects within the research agenda.

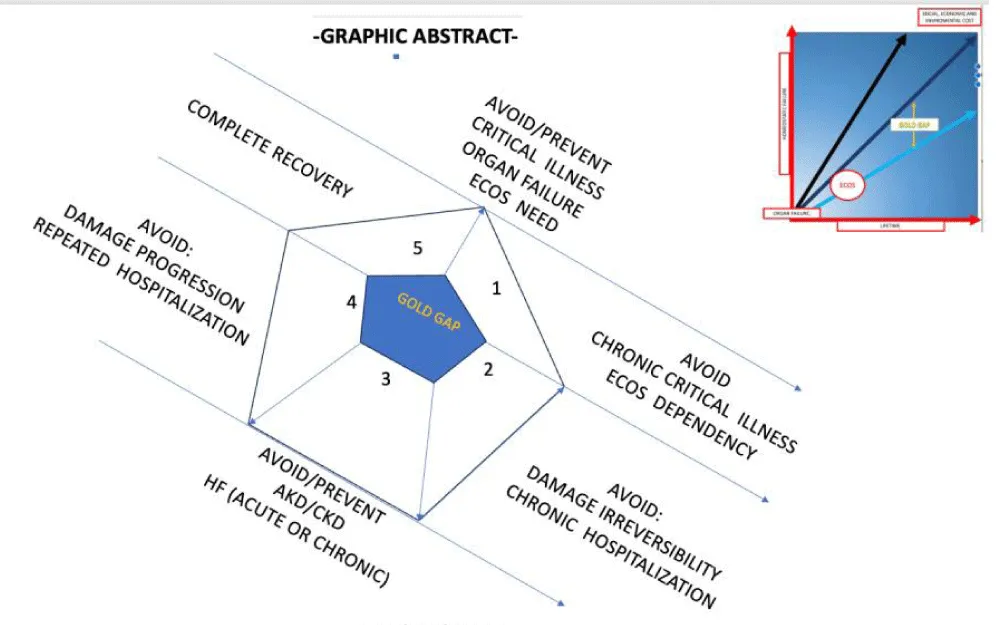

Graphical abstract: In order to understand the potential benefit of ECOS within different CRS clinical scenarios, its role as an inflection point in the natural history of disease must be adressed (i.e. CRRT sorbent use may represent the inflection point for a patient with sepsis-associated CRS type 5). Yet, surogate markers of long term clinical, economical and enviromental benefit remains to be described. Ideally, such surogate markers may serve as clinical road mark, goals and public health evaluation tools (i.e. number of HD years saved by preventing an AKI episode to become ESRD).

The term “Cardiorenal Syndrome” [CRS] is used to refer to the vast array of interrelated, bidirectional interactions between heart-kidney derangements [1,2].

Given its wide clinical spectrum, a conceptual framework based on physiopathological mechanisms and chronological evolution is used to classify it: [1,2].

Type 1 – Acute cardiac failure results in Acute Kidney Injury [AKI].

Type 2 – Chronic cardiac dysfunction causes progressive Chronic Kidney Disease [CKD].

Type 3 – Abrupt and primary renal derangements cause acute cardiac dysfunction.

Type 4 – Primary CKD contributes to cardiac dysfunction [i.e., coronary disease).

Type 5 – [secondary] – Acute or chronic systemic disorders causes heart and kidney derangements.

Given the complex nature of CRS, operational definitions have been developed, allowing diagnostic-therapeutic approaches and clinical research standardizations. Such definitions involve surrogate markers of physiological processes, and must be taken into account while solving clinical issues, or developing and interpreting clinical research, taking into account the advantages and biases regarding choosing different biomarkers and clinical outcomes.

AKI refers to an abrupt decrease of renal function as per AKIN/KDIGO definition, giving place to urea and nitrogenous waste product accumulation, dysregulation of extracellular volume, acid-base and electrolytes homeostasis derangements [3]. AKI is a dynamic process in terms of its severity and clinical progression: kidney function may improve, remain unchanged or get worse, giving place to renal recovery, transient or persistent AKI, Acute Kidney Disease [AKD] or CKD.

Creatinine measurements are widely available, inexpensive and its interpretation is broadly known among health care professionals, making it a perfect biomarker to a world-wide operational definition of AKI. However, creatinine may not be the ideal early biomarker to take into account in the natural history of AKI [4].

Biomarkers, including Neutrophil Gelatinase- Associated Lipocalin [NGAL], kidney injury molecule-1 [KIM-1], interleukin 18 [IL-18], liver-type fatty acid binding protein [L-FABP], and urinary calprotectin has been used in the clinical approach to kidney injury. Rather than replacing creatinine and oliguria criteria, kidney damage biomarkers will help creating a more comprehensive, earlier approach to AKI [3-6].

Subclinical AKI [SAKI] [3] represents a category of kidney damage, diagnosed by elevations of tubular damage biomarkers alone, which might or might not be accompanied by subsequent rise in serum creatinine levels and/or oliguria [3-5].

Heart Failure [HF] is a clinical syndrome resulting from any structural or functional derangement impairing the ventricle ability to fill with or eject blood, being the hemodynamic sine qua non condition the heart not being able pump enough blood to accomplish the body needs, or doing so at the cost of high filling pressures, with or without accompanying physical signs and symptoms [7,8].

Also, HF may be classified as acute [AHF], chronic [CHF], or Acutely Decompensated Heart Failure [ADHF] [9]. In the context of patients with decompensated HF, Worsening Renal Function [WRF] refers to an increase in serum creatinine of ≥ 0.3 mg/dL within 72 hours [7,9].

The American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association [ACC/AHA] stages HF from A to D. HF is also subclassified as left-sided [i.e., caused by left ventricle, aortic or mitral dysfunction] or right-sided [i.e. right ventricle, or tricuspid valve dysfunction). The two types of dysfunction may occur independently or concurrently, being the clinical overlap is of utmost importance; Left HF may lead to right HF, and most patients with right HF have some concurrent left HF [8].

HF caused by Left Ventricular [LV] dysfunction is divided according to LV Ejection Fraction [LVEF] into reduced [HFrEF], mid-range [HFmrEF], preserved ejection fraction [HFpEF] or recovered LV ejection fraction [10,11].

There is a high heterogenicity among the possible causes of acute, chronic or acute on chronic kidney and heart derangements. However, common phisyopathological pathways have been described, including neurohumoral adaptations, hemodynamic changes [including reduced renal perfusion, and increased renal venous pressure), Right Ventricular [RV] / Left Ventricular [LV] dysfunction, oxidative stress and proinflammatory pathways [2,8].

The complex physio pathological derangements that give place to the wide variety of clinical presentations of cardiorenal syndrome types are explained through a theoretical framework based on the existence of arterial underfilling, venous congestion, and neurohormonal derangements, inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, and GFR changes [8-12].

Deranged LV function may lead to reduced stroke volume, low cardiac output and arterial underfilling, accompanied by elevated atrial pressures, and venous congestion. These hemodynamic changes trigger compensatory neurohumoral responses [2,6,8]:

Activation of the sympathetic nervous system, caused by impaired baroreceptor reflexes results in increased renin release from the juxtamedullary renal cells. Sympathetic activation patients with HF is aimed to maintain perfusion through an increase in contractility, lusitropy, and vasoconstriction, but also increases cardiac afterload, that may ultimately lead to reduced renal perfusion. Of note, compensatory changes in GFR may not initially reflect deranged renal function itself.

Renin synthesis is also influenced by the hydrostatic pressure sensed at glomerular afferent arterioles, and the reduced quantity of chloride delivered to the macula densa.

As chloride is a primary modulator of tubular feedback; change in serum chloride is a primary determinant of changes in plasma volume and in activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system. In HF patients under diuretic therapy hypochloremia is frequently accompanied by chloride depletion metabolic alkalosis, which can lead to premature discontinuation of diuretic even in the presence of volume overload.

Adenosine is released in response to an increased sodium load in the distal tubule and via adenosine type 1 receptors gives place to constriction of afferent arterioles and reduction of renal blood flow. Adenosine type 2 receptors gives place to rising renin liberation, increasing sodium reabsorption in proximal tubules.

Increased renin leads to increased angiotensin II [Ang II], that causes renal efferent arteriolar vasoconstriction and an increased fraction of renal plasma flow filtered at the glomerulus, with increase in peritubular oncotic pressure and reduced hydrostatic pressure causing enhanced reabsorption of sodium in the proximal tubules.

Ang II mediates the oxidative stress via reactive oxygen species [ROS] formation in cardiac and renal tissue leading to inflammation and hypertension, promotes the aldosterone-mediated reabsorption of sodium in the distal tubules and induces renal expression of endothelin-1 [ET-1].

Increase in ET-1, promote salt and water retention and systemic vasoconstriction, a as it is, a proinflammatory and profibrotic peptide that promotes salt and water retention.

Increased Arginine vasopressin [AVP], antidiuretic hormone release in response to serum osmolality, increasing water retention in the collecting duct. AVP increases stimulate renin secretion via activation of V2 receptors or reduction in sodium concentration at the macula densa.

The aforementioned neurohumoral changes lead to a change in urea: creatinine reabsorption ratio, being blood urea nitrogen a surrogate marker of neurohormonal activation in patients with HF. These derangements overwhelm effects of natriuretic peptides, nitric oxide, prostaglandins, and bradykinin systems on vasodilation and natriuresis [2,8-11].

Within this framework, ECOS interventions in CRS may be categorized in hemodynamic support (in patients with arterial underfilling because of cardiac pump failure), volume optimization through UF/PD/HD in patients with venous congestion, sorbent use in patient with neurohumoral derangements, inflammation, or endothelial dysfunction [13], and RRT in patients with GFR below stablished therapeutic threshold. Of note, the different types of support are not mutually exclusive, and a single patient may receive or more of them at the same or different time points in their path to recovery [14-16].

Of note, the evaluation of Evidence Based Interventions (EBIs) directly aimed to CRS poses special challenges, since no experimental model or translational medicine approaches can be easily performed. Also, there are no “pure single CRS type” clinical scenarios, and the clinical outcomes used in large clinical trials rarely are aimed to the evaluation of cardiorenal interaction themselves. Within the following sections, a brief summary of the clinical trials aimed to evaluate the use of ECOS in CRS scenarios will be made (Table 1).

| Table 1: Clinical benefits and possible inflection points of ECO in different CRS scenarios. | ||||

| CRS Type | ECOS type. | ECOS benefits | Clinical benefits. | Homeostatic benefit. |

| 1 | ECMO | Hemodynamic support. | ECOS provides cardiovascular support, maintaining systemic (and thus renal perfusion) despite cardiac failure until recovery of cardiac function. | Hemodynamic support prevents the development of hypoperfusion and/or ischemia, preventing organ failure to occur. |

| 2 | UF | UF resolves fluid overload preventing the perpetuation of neurohumoral derangements. | Achieving euvolemic state. Prevention of further neurohumoral derangements. |

Resolving fluid overloads prevents both neurohumoral derangements and the perpetuation of both cardiac and renal derangements linked to fluid overload. |

| 3 | RRT | Renal function replacement prevents progression to both AKD and cardiac derangements. | Avoid metabolic and cardiovascular complications associated to AKI. Prevents multiorgan failure cascade to develop. |

Prevents progression from single organ to multiorgan failure, bridge from single organ failure to complete recovery. |

| 4 | RRT | Renal function replacement prevents development of cardiac failure. | Avoid metabolic and cardiovascular derangements associated to CKD, role of sorbents in modulating inflammation to be determined. | Maintain homeostasis, prevent organ crosstalk to perpetuate cardiovascular damage. |

| 5 | Single or multiple ECOS techniques may be used according to clinical needs. | Hemodynamic supports. Oxygenation improvement. Achieving euvolemia Cytokine removal Immunomodulation. |

Prevent single organ failure worsening Prevent multiorgan failure to develop. Prevent chronic organ failure to develop/perpetuate. |

Prevent single organ failure worsening. Prevent progression from single to multiorgan failure. Prevent development of chronic organ failure. Achieve complete recovery. Immunomodulation. |

Type 1 CRS, the role of ECOS as hemodynamic support

Being among one the most representative clinical scenarios of Type 1 CRS, cardiogenic shock may be a suitable model of the expected benefit of ECOS in other CRS type 1 scenarios, mainly providing hemodynamic support.

Among the possible scenarios of cardiogenic shock, clinical trials on trauma-related cardiac arrest assumes otherwise previously healthy population (thus, without bias related to the existence of acute-on-chronic failures). Still, the biases regarding the existence of concomitant kidney injury not related to cardiorenal interactions cannot be excluded, as hemorrhagic shock resulting from cardiac and vascular trauma is the principal mechanism of intractable shock and cardiac arrest in trauma patients [17].

In a systematic review and meta- analysis of ECMO in adult patients with severe trauma that involved 36 studies, 26.7% of patients treated with ECMO were reported to have renal complications. Pooled survival rate was 65.9%, (39.0% for VA ECMO and 72.3%, for VV ECMO), as expected, patients receiving ECMO support tend to exhibit higher survival rates and lower rates of neurological complications the subgroup of patients with traumatic brain injury, and hemorrhage and bleeding complications accounted for an important limitation of ECMO [17].

In a nationwide observational cohort study comparing acute myocardial infarction-related cardiogenic shock (AMICS) patients treated with Impella (ABIOMED, Danvers, MA, USA) and/or VA-ECMO, AKI was described to occur in 44% vs. 53%, (p < 0.001) of patients, and acute liver failure 7% vs. 12%, of patients (p < 0.001). Impella patients were directly discharged home more often, with shorter hospital stays and lower costs [18].

By taking into account clinical outcomes regarding multiple organs, the results of this study provides insight into the significance of multiorgan crosstalk in this patients as well as the impact that choosing over different ECOS technique may have over resource consumption and health related economic cost [18].

The ECMO-CS (Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation in the Therapy of Cardiogenic Shock) is a multicentric, randomized trial that comparing immediate implementation of VA-ECMO vs. initial conservative therapy in patients with rapidly deteriorating /severe cardiogenic shock [19].

In the ECMO-CS trial, no significant differences were found regarding the composite of death from any cause, resuscitated circulatory arrest, and implementation of another mechanical circulatory support at 30 days. Neither there were differences regarding points included all-cause mortality, neurological outcome, significant bleeding, leg ischemia, pneumonia, sepsis, and technical complications. Of note, the most common cause of cardiogenic shock was myocardial infarction, which implies underlying chronic heart failure in a proportion of patients [19].

Multiple clinical trials have assessed the use of ECMO in scenarios that involves CRS type 1, being the improve of micro and microcirculation the main mechanism by which ECMO contributes, but the inclusion of specific perfusion related variables (i.e. capillaroscopy, lactate levels) are lacking since the evaluation of the risk/benefit and/or cost effectiveness evaluation of ECMO (as a resource consuming, increasingly used) option has been prioritize [20,21].

Type 2 CRS, the role of ultrafiltration in preventing further cardiac derangements

Animal models of CRS type 2 have been developed (i.e. Coronary artery ligand / Unilateral nephrectomy); this model may be insightful in terms of tracking the neurohumoral cascade, hemodynamic changes and oxidative stress mediators [22].

However, animal models may not entirely predict clinical response in patients since they do not include crucial variables such as previous and/or concomitant organic derangements, (including cardiac preconditioning, collateral circulation, baseline comorbidities such as diabetes or cirrhosis, neural interactions) that contributed to de development of chronic heart failure on the first place [22-24].

Also to be taken into account, pharmacological interactions may not be represented in experimental models: this is a very important factor to take into account given that diuretic resistance is one of the clinical problems that leads to the need of ECOS (specifically UF methods to achieve euvolemia) in the setting of CRS type 2 [22,25].

Equally important, while implementing a standard definition of worsening renal function may be made based on standardized AKI criteria, acute changes in GFR in the context of CHF may not always reflect the loss of kidney function itself, nor necessarily correlates with adverse clinical outcomes, such as minimal decrease of GFR after Starting ACE inhibitors [23-25].

Given the previously stated facts, it is clear that the development of large scale trials and politics focused on prevention of ESRD in patients with HF as suggested by HF guidelines [8]. Also, the optimal timing and modality to consider RRT in this specific population remains to be clarified. Until now, clinical trials on RRT/UF in CRS type 2 patients are focused on evaluating the risk/benefit and cost/effectiveness of the use of RRT in terms of mortality and, in the case of acute on chronic HF exacerbation, achieving euvolemia through UF/RRT [26].

Even when RRT has been extensively studied in the context of CRS type 1, the early use of UF in the context of CHF with diuretic resistance is a major subject in the research agenda, as a useful tool for the removal of c faster volume removal and improving renal hemodynamics. Of note, UF may be used as an adjunct to diuretics in patients with CRS [27,28].

Until now, volume removal via UF has been outlined as a safe therapeutic option both alone and in combination with diuretic therapy. Similarly, the use of Peritoneal Dialysis (PD) has been outlined as a safe and effective method to achieve negative fluid balance and euvolemia [29,30].

Among patients with decompensated heart failure with volume overload and poor diuretic response, the use of UF has been linked to a trend towards lower creatinine at discharge, but no significant difference in GFR. Also, a trend towards the use of UF with greater weight loss, volume removal and reduction of readmission in patients treated with UF, but no significant reduction in length of hospital stay or 30-day mortality [29,30].

Type 3 CRS, ECOS preventing progressive cardiac failure

Type 3 CRS refers to abrupt and primary renal derangements that subsequently cause acute cardiac dysfunction [31]. By definition, CRS type 3 can occur in a wide variety of clinical scenarios, for which the pathophysiological mechanism common to all of the possible CRS type 3 causes may be best understood by using experimental models.

Of note, the definition of cardiac dysfunction related to AKI may include heart failure because of arrhythmias, myocardial ischemia, or fluid retention with or without arterial hypertension, thus highlighting the difficulty of having a standard definition of cardiac damage in the context of CRS type 3.

Interestingly, in experimental models, cardiac dysfunction does not seem to be chronologically parallel from excretory kidney dysfunction [31]. Moreover, even when diagnosis of subclinical AKI via tubular damage biomarkers in at risk population (i.e. identified by electronic sniffers), [32,33] biomarkers of cardiac damage and early echocardiographic evaluation may not be assessed routinely, except for selected clinical scenarios such as perioperative AKI on patients with high cardiovascular risk [34].

As Intra-renal immune activation, production of vasoconstrictive substances, cardiac mitochondriopathy, impaired redox balance, and activation pro-apoptotic pathways have been implied as the main myocardial damage pathways in CRS3, early detection of cardiac damage in AKI patients (i.e. those with risk factors for “ myocardial frailty”) may be an important component of early CRS type 3 identification, in whatever clinical scenario AKI as a primary entity may develop [35,36].

Clinical trials on the best (i.e. more efficient approach) clinical pathway to assess cardiac function for each given CRS 3 scenario remains to be fully described, as their natural history, window of opportunity, evidence based therapeutic bundles and expected timeline is specific by definition.

As an example, 48 hours postoperative Troponin I may be taken in patients who experience postoperative AKI, while bedside echocardiography may be the best choice for patients who developed AKI after polytrauma. Evidence based bundles towards “cardiorenal assessment” as well as the earliest timing and modality to start ECOS to achieve maximum clinical results (i.e. greater number of cases of AKI being prevented to progress to CKD/HF) remain to be fully standardized for every possible clinical scenario [31-36].

Type 4 CRS – The role of ECOS in preventing further homeostatic damage

The association between CKD and ESRD with cardiac function derangement and adverse cardiovascular outcomes has been long recognized, even in patients under chronic RRT with good hemodialytic efficacy [37,38]. Patients with CKD have a 10 fold increase in mortality risk when compared with general population, with more than 50% of CKD population mortality being attributable to cardiovascular disease, mainly coronary artery disease, valvular dysfunction, arrhythmias, and cardiomyopathies [37,38].

Representative cardiovascular changes associated with CRS type 4 include cardiac remodeling, neurohumoral abnormalities, increased ischemic risk, left ventricular hypertrophy, left diastolic dysfunction, decreased coronary flow and coronary calcification. Of note all of them may be present before the patients get the diagnosis of ESRD, or even in the presence of risk factors, such as smoking, obesity or hypertension, without the presence of CKD, which may imply, according to the Bradford Hill criteria, that renal function derangements are not directly the only cause of cardiac derangements, but likely an accompanying manifestation of a common physiopathological pathway that, within the progress of the natural history of disease, contributes itself to further derangements in cardiovascular homeostasis [37-39].

As an example, a patient that has already developed diastolic dysfunction due to obesity may have further derangements in diastolic function associated with sodium and water overload and chronic inflammation because of uremic toxins after developing CKD [37-39].

Once the patient develops ESRD and becomes dialysis dependent, further monocyte stimulation because of interactions between the immune cells and hemofilter surfaces perpetuates chronic inflammation, cytokine production, endothelial dysfunction, smooth muscle proliferation, and accelerated atherosclerosis [37-39].

Among the inflammatory pathways, mitochondria dysfunction can trigger inflammatory pathways by releasing Damage-Associated Molecular Patterns (DAMPs), which are recognized by immune receptors within cells, including Toll-Like Receptors (TLR) nucleotide-binding domain, leucine-rich-containing family pyrin domain-containing-3 (NLRP3) inflammasome, and the cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP)-adenosine monophosphate (AMP) synthase (cGAS)-stimulator of interferon genes (cGAS-STING) pathway, perpetuating the increase in increased expression of cytokines and chemokines [39-41].

The existence of inflammatory pathways which are not attenuated by UF/HD partially explains the increased cardiovascular risk even in patients who are not volume overloaded nor uremic, as well as the clinical benefit in cardiovascular endpoints when targeting the inflammatory cascade [40-43].

However, whatever or not the addition of sorbents to RRT may be helpful in attaining control of the inflammatory pathways remains uncertain, but adding chemokine reduction strategies through sorbent columns use may represent an strategy towards attenuating further cardiovascular derangement in ESRD patients, which may translate in diminished mortality, diminished hospital admission rates and overall better quality of life and diminished health resource consumption [40-43].

Type 5 CRS – ECOS benefits beyond a single scenario

In CRS type 5, the heart and kidneys are affected by a systemic illness, leading to concurrent dysfunction in both organs. As this type of CRS may include many different clinical scenarios, both acute and chronic, it may be the most heterogeneous class within the CRS classifications. Acute CRS type 5 scenarios may include sepsis, preeclampsia, and drug toxicities, while chronic scenarios may include Diabetes, Fabry disease and cirrhosis, thus meaning that physiopathological mechanism involved may go from hemodynamic derangements that affect both cardiac and renal perfusion to inflammatory pathways and chronic pathologic deposition within the extracellular matrix. Beyond the difficulties that CRS type 5 poses to the creation of a single diagnostic-therapeutic approach, it can be used as a multiperspective model to understand the clinical benefits that ECOS may provide to derangements in cardiorenal interactions [44-50]:

- As a hemodynamic support in scenarios where arterial underfilling (defined as a decreased effective arterial blood volume) represents the cardinal element of end-organ derangements.

- As a mean to improve oxygen delivery either via extracorporeal oxygenation or hemodynamic support.

- As a mean to achieve euvolemia in clinical scenarios were volume overload perpetuate vascular damage a neurohumoral activation.

- As a mean for removing cytokines and proinflammatory mediator via hemadsorption.

- As a mean for detoxifying from either endogenous or exogenous deleterious substances (i.e. From liver support removing bilirubin to sorbent use to remove exogenous toxins, including low and middle molecular weight toxins.

Moreover, thanks to the temporal heterogenicity of the possible clinical scenarios, it can be used to assess the best chronological window to improve clinical outcomes thus changing the paradigm from considering ECOS and almost last resource to a window of opportunity that may be implemented earlier during the disease course in order to either avoid irreversible organ failure, avoid ECOS long term dependency, prevent progression to chronic end-organ damage, avoid the need of repeated hospitalization or even achieve full recovery after an otherwise not preventable life threatening event.

Within the last 50 years, ECOS has evolved from being a nearly experimental, last resource to a standardized, evidence-based therapy to be performed in selected patients worldwide. Alongside with the development of better ECOS therapies it became clear that both crosstalk and ECOS–patient interactions played a significant role in the clinical course and outcomes to be expected.

Cardiorenal syndrome represents a unique opportunity of comprehension of the multiorgan crosstalk involved in a wide variety of cardiovascular disease: one thought to be independent, it has become clear that renal and cardiac function are closely related to each other, and its interrelations within the framework of concurrent derangements can be best understood within the frame of cardiorenal syndrome. Moreover, the interactions within multiple crosstalk and the different ECOS system for every CRS scenario are still to be fully described.

Most importantly, CRS has become a model to further understand the challenges, benefits and possible applications of ECOS therapies, as well a prototype for future perspectives on the possible benefits and the best way to approach ECOS as a high-resource-consuming intervention that nonetheless may be sustainable within the appropriate policies, and more importantly , in terms of saving and preventing further healthcare resources if prevention of further organ damage or even reversing organ failures is achieved.

Cardiorenal syndrome represents an organ crosstalk pathway with arterial underfilling, vascular derangements, inflammatory pathways and neurohumoral derangements among its most important physiopathological elements. Cardiorenal derangements interactions can be understood within the frame of 5 types of cardiorenal syndrome. Therapeutic approaches to CRS have traditionally focused on medical therapies aimed to relieve volume overload, improve cardiac output, regulate neurohumoral derangements and modulate proinflammatory pathways.

Within the recent years, ECOS techniques have proven to be useful at improving volume overload, arterial underfilling, oxygen delivering, cytokine profile and neurohumoral derangement in various clinical scenarios, giving the opportunity to avoid organ failure, organ failure progression, chronic critical illness, end-organ damage reaches irreversibility, prevent chronic organ failure and even fully recover organ function. Within the years to come the best timeframe, follow-up surrogate markers and public health benefits and challenges remain to be established. Moreover, evidence based “cardiorenal bundles” and strategies within different CRS scenarios are yet to be described, while public health policies and technological advances may also improve and expand clinical applications of ECOS within the frame of CRS.

- Ronco C, Bellasi A, Di Lullo L. Cardiorenal syndrome: An overview. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis [Internet]. 2018;25(5):382–90. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1053/j.ackd.2018.08.004

- Kumar U, Wettersten N, Garimella PS. Cardiorenal syndrome: Pathophysiology. Cardiol Clin [Internet]. 2019;37(3):251–65. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ccl.2019.04.001

- Chawla LS, Bellomo R, Bihorac A, Goldstein SL, Siew ED, Bagshaw SM, et al. Acute kidney disease and renal recovery: consensus report of the Acute Disease Quality Initiative (ADQI) 16 Workgroup. Nat Rev Nephrol [Internet]. 2017;13(4):241–57. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nrneph.2017.2

- Waikar SS, Bonventre JV. Creatinine kinetics and the definition of acute kidney injury. J Am Soc Nephrol [Internet]. 2009;20(3):672–9. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1681/ASN.2008070669

- Haase M, Kellum JA, Ronco C. Subclinical AKI--an emerging syndrome with important consequences. Nat Rev Nephrol [Internet]. 2012;8(12):735–9. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nrneph.2012.197

- John JS, Deepthi RV, Rebekah G, Prabhu SB, Ajitkumar P, Mathew G, et al. Usefulness of urinary calprotectin as a novel marker differentiating functional from structural acute kidney injury in the critical care setting. J Nephrol [Internet]. 2023;36(3):695–704. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40620-022-01534-3

- Gembillo G, Visconti L, Giusti MA, Siligato R, Gallo A, Santoro D, et al. Cardiorenal Syndrome: New Pathways and Novel Biomarkers. Biomolecules [Internet]. 2021;11(11):1581. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3390/biom11111581

- Ostrominski JW, DeFilippis EM, Bansal K, Riello RJ 3rd, Bozkurt B, Heidenreich PA, et al. Contemporary American and European Guidelines for Heart Failure Management: JACC: Heart Failure Guideline Comparison. JACC Heart Fail [Internet]. 2024;12(5):810–25. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jchf.2024.02.020

- McDonagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M, Gardner RS, Baumbach A, Böhm M, et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J [Internet]. 2021;42(36):3599–726. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab368

- Wilcox JE, Fang JC, Margulies KB, Mann DL. Heart Failure With Recovered Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction: JACC Scientific Expert Panel. J Am Coll Cardiol [Internet]. 2020;76(6):719–34. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2020.05.075

- Young JB, Eknoyan G. Cardiorenal Syndrome: An Evolutionary Appraisal. Circ Heart Fail [Internet]. 2024;17(6):e011510. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.123.011510

- McCallum W, Sarnak MJ. Cardiorenal Syndrome in the Hospital. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol [Internet]. 2023;18(7):933–45. Available from: https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.0000000000000064

- Ramírez-Guerrero G, Ronco C, Reis T. Cardiorenal Syndrome and Inflammation: A Forgotten Frontier Resolved by Sorbents? Cardiorenal Med [Internet]. 2024;14(1):454–8. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1159/000540123

- Selewski DT, Wille KM. Continuous renal replacement therapy in patients treated with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Semin Dial [Internet]. 2021;34(6):537–49. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/sdi.12965

- Totapally A, Bridges BC, Selewski DT, Zivick EE. Managing the kidney - The role of continuous renal replacement therapy in neonatal and pediatric ECMO. Semin Pediatr Surg [Internet]. 2023;32(4):151332. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sempedsurg.2023.151332

- Lane SF, Harvey-Jones E, Ward O, Davies R. Renal replacement and extracorporeal therapies in critical care: current and future directions. Acute Med [Internet]. 2023;22(3):154–62. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37746685/

- Zhang Y, Zhang L, Huang X, Ma N, Wang P, Li L, et al. ECMO in adult patients with severe trauma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Med Res [Internet]. 2023;28(1):412. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40001-023-01390-2

- Bogerd M, Ten Berg S, Peters EJ, Vlaar APJ, Engström AE, Otterspoor LC, et al. Impella and venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in cardiogenic shock complicating acute myocardial infarction. Eur J Heart Fail [Internet]. 2023;25(11):2021–31. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1002/ejhf.3025

- Ostadal P, Rokyta R, Karasek J, Kruger A, Vondrakova D, Janotka M, et al. Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation in the Therapy of Cardiogenic Shock: Results of the ECMO-CS Randomized Clinical Trial. Circulation [Internet]. 2023;147(6):454–64. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.122.062949

- Yu Z, Li G. VA-ECMO for infarct-related cardiogenic shock. Lancet [Internet]. 2024;403(10443):2487. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(24)00958-9

- Lüsebrink E, Binzenhöfer L, Hering D, Villegas Sierra L, Schrage B, Scherer C, et al. Scrutinizing the Role of Venoarterial Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation: Has Clinical Practice Outpaced the Evidence? Circulation [Internet]. 2024;149(13):1033–52. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.123.067087

- Harrison JC, Smart SDG, Besley EMH, Kelly JR, Read MI, Yao Y, et al. A Clinically Relevant Functional Model of Type-2 Cardio-Renal Syndrome with Paraventricular Changes consequent to Chronic Ischaemic Heart Failure. Sci Rep [Internet]. 2020;10(1):1261. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-58071-x

- Marassi M, Fadini GP. The cardio-renal-metabolic connection: a review of the evidence. Cardiovasc Diabetol [Internet]. 2023;22(1):195. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-023-01937-x

- McCallum W, Tighiouart H, Ku E, Salem D, Sarnak MJ. Trends in Kidney Function Outcomes Following RAAS Inhibition in Patients With Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction. Am J Kidney Dis [Internet]. 2020;75(1):21–9. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2019.05.010

- Chávez-Iñiguez JS, Sánchez-Villaseca SJ, García-Macías LA. Síndrome cardiorrenal: clasificación, fisiopatología, diagnóstico y tratamiento. Una revisión de las publicaciones médicas [Cardiorenal syndrome: classification, pathophysiology, diagnosis and management. Literature review]. Arch Cardiol Mex [Internet]. 2022;92(2):253–63. Available from: https://doi.org/10.24875/ACM.20000183

- Guo S, Chen Y, Huo Y, Zhao C, Zhang K, Zhang X, et al. Comparison of early and delayed strategy for renal replacement therapy initiation for severe acute kidney injury with heart failure: a retrospective comparative cohort study. Transl Androl Urol [Internet]. 2023;12(5):715–26. Available from: https://doi.org/10.21037/tau-23-146

- Villegas-Gutiérrez LY, Núñez J, Kashani K, Chávez-Iñiguez JS. Kidney Replacement Therapies and Ultrafiltration in Cardiorenal Syndrome. Cardiorenal Med [Internet]. 2024;14(1):320–33. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1159/000539547

- Lim SY, Kim S. Pathophysiology of Cardiorenal Syndrome and Use of Diuretics and Ultrafiltration as Volume Control. Korean Circ J [Internet]. 2021;51(8):656–67. Available from: https://doi.org/10.4070/kcj.2021.0996

- Jentzer JC, Bihorac A, Brusca SB, Del Rio-Pertuz G, Kashani K, Kazory A, et al. Contemporary Management of Severe Acute Kidney Injury and Refractory Cardiorenal Syndrome: JACC Council Perspectives. J Am Coll Cardiol [Internet]. 2020;76(9):1084–101. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2020.06.070

- Guerrero Cervera B, López-Vilella R, Donoso Trenado V, Peris-Fernández M, Carmona P, Soldevila A, et al. Analysis of the usefulness and benefits of ultrafiltration in cardiorenal syndrome: A systematic review. ESC Heart Fail [Internet]. 2025;12(2):1194–202. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1002/ehf2.15125

- Patschan D, Marahrens B, Jansch M, Patschan S, Ritter O. Experimental Cardiorenal Syndrome Type 3: What Is Known so Far? J Clin Med Res [Internet]. 2022;14(1):22–7. Available from: https://www.jocmr.org/index.php/JOCMR/article/view/4639

- Hoste EA, Kashani K, Gibney N, et al. Impact of electronic-alerting of acute kidney injury: workgroup statements from the 15th ADQI Consensus Conference. Can J Kidney Health Dis [Internet]. 2016;3:10. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40697-016-0101-1

- Zou C, Wang C, Lu L. Advances in the study of subclinical AKI biomarkers. Front Physiol [Internet]. 2022 24;13:960059. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2022.960059

- Duceppe E, Parlow J, MacDonald P, Lyons K, McMullen M, Srinathan S, et al. Canadian Cardiovascular Society Guidelines on Perioperative Cardiac Risk Assessment and Management for Patients Who Undergo Noncardiac Surgery. Can J Cardiol [Internet]. 2017;33(1):17–32. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cjca.2016.09.008

- Okpara R, Pena C, Nugent K. Cardiorenal Syndrome Type 3 Review. Cardiol Rev [Internet]. 2024;32(2):140–5. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1097/crd.0000000000000491

- Bagshaw SM, Hoste EA, Braam B, Briguori C, Kellum JA, McCullough PA, et al. Cardiorenal syndrome type 3: pathophysiologic and epidemiologic considerations. Contrib Nephrol [Internet]. 2013;182:137–57. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1159/000349971

- Minciunescu A, Genovese L, deFilippi C. Cardiovascular Alterations and Structural Changes in the Setting of Chronic Kidney Disease: a Review of Cardiorenal Syndrome Type 4. SN Compr Clin Med [Internet]. 2023;5(1):15. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42399-022-01347-2

- Sessa C, Granata A, Gaudio A. G Ital Nefrol [Internet]. 2020;37(1):2020-vol1. Published 2020 Feb 12. Available from: https://giornaleitalianodinefrologia.it/en/2020/02/vol-37-n-1-gennaio-febbraio-2020/

- Amador-Martínez I, Aparicio-Trejo OE, Bernabe-Yepes B, Aranda-Rivera AK, Cruz-Gregorio A, Sánchez-Lozada LG, et al. Mitochondrial Impairment: A Link for Inflammatory Responses Activation in the Cardiorenal Syndrome Type 4. Int J Mol Sci [Internet]. 2023;24(21):15875. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms242115875

- Ramírez-Guerrero G, Ronco C, Reis T. Cardiorenal Syndrome and Inflammation: A Forgotten Frontier Resolved by Sorbents? Cardiorenal Med [Internet]. 2024;14(1):454–8. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1159/000540123

- McCullough PA, Chan CT, Weinhandl ED, Burkart JM, Bakris GL. Intensive Hemodialysis, Left Ventricular Hypertrophy, and Cardiovascular Disease. Am J Kidney Dis [Internet]. 2016;68(5 Suppl 1):S5–14. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2016.05.025

- Li H, Liu T, Yang L, Ma F, Wang Y, Zhan Y, et al. Knowledge landscapes and emerging trends of cardiorenal syndrome type 4: a bibliometrics and visual analysis from 2004 to 2022. Int Urol Nephrol [Internet]. 2024;56(1):155–66. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11255-023-03680-4

- Dellepiane S, Medica D, Guarena C, Musso T, Quercia AD, Leonardi G, et al. Citrate anion improves chronic dialysis efficacy, reduces systemic inflammation and prevents Chemerin-mediated microvascular injury. Sci Rep [Internet]. 2019;9(1):10622. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-019-47040-8

- Mehta RL, Rabb H, Shaw AD, Singbartl K, Ronco C, McCullough PA, et al. Cardiorenal syndrome type 5: clinical presentation, pathophysiology and management strategies from the eleventh consensus conference of the Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative (ADQI). Contrib Nephrol [Internet]. 2013;182:174–94. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1159/000349970

- Chávez-Iñiguez JS, Sánchez-Villaseca SJ, García-Macías LA. Síndrome cardiorrenal: clasificación, fisiopatología, diagnóstico y tratamiento. Una revisión de las publicaciones médicas [Cardiorenal syndrome: classification, pathophysiology, diagnosis and management. Literature review]. Arch Cardiol Mex [Internet]. 2022;92(2):253–63. Available from: https://doi.org/10.24875/acm.20000183

- Virzì GM, Clementi A, Brocca A, de Cal M, Marcante S, Ronco C. Cardiorenal Syndrome Type 5 in Sepsis: Role of Endotoxin in Cell Death Pathways and Inflammation. Kidney Blood Press Res [Internet]. 2016;41(6):1008–15. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1159/000452602

- Ilagan J, Sahani H, Saleh AB, Tavakolian K, Mararenko A, Udongwo N, et al. Type 5 Cardiorenal Syndrome: An Underdiagnosed and Underrecognized Disease Process of the American Mother. J Clin Med Res [Internet]. 2022;14(10):395–9. Available from: https://doi.org/10.14740/jocmr4792

- Brocca A, Virzì GM, Pasqualin C, Pastori S, Marcante S, de Cal M, et al. Cardiorenal syndrome type 5: in vitro cytotoxicity effects on renal tubular cells and inflammatory profile. Anal Cell Pathol (Amst) [Internet]. 2015;2015:469461. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/469461

- Galassi A, Magagnoli L, Fasulo E, Stucchi A, Restelli E, Moro A, et al. Forced diuresis oriented by point-of-care ultrasound in cardiorenal syndrome type 5 due to light chain myeloma—The role of hepatic venogram: A case report. Clin Case Rep [Internet]. 2021;9(4):2453–9. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1002/ccr3.4069

- Vega-Vega O, Ronco C, Martínez-Rueda AJ. Pushing the boundaries of hemodialysis: innovations in membranes and sorbents. Rev Invest Clin [Internet]. 2023;75(6):274–88. Available from: https://doi.org/10.24875/ric.23000223