More Information

Submitted: October 31, 2025 | Approved: November 05, 2025 | Published: November 10, 2025

How to cite this article: Chiang CM. Cardiopulmonary Rescue before Fixation: Targeted Pigtail Decompression for Hyperacute Unilateral Lung Decompensation Enabling ORIF in Bilateral Open Distal Femur Fractures. J Cardiol Cardiovasc Med. 2025; 10(6): 133-136. Available from:

https://dx.doi.org/10.29328/journal.jccm.1001220

DOI: 10.29328/journal.jccm.1001220

Copyright license: © 2025 Chiang CM. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Keywords: Polytrauma; Pigtail catheter; Unilateral pulmonary edema; Re‑expansion pulmonary edema; Negative‑pressure pulmonary edema; Fat embolism; Fracture fixation timing

Cardiopulmonary Rescue before Fixation: Targeted Pigtail Decompression for Hyperacute Unilateral Lung Decompensation Enabling ORIF in Bilateral Open Distal Femur Fractures

Chi-Ming Chiang1,2*

1Center for General Education, Chung Yuan Christian University, No. 200, Zhongbei Rd., Zhongli District, 320 Taoyuan, Taiwan, Republic of China

2Department of Orthopedics, National Yang Ming Chiao Tung University Hospital, No. 169, Xiaoshe Rd., 260 Yilan, Taiwan, Republic of China

*Address for Correspondence: Chi-Ming Chiang, MD, PhD, Center for General Education, Chung Yuan Christian University, No. 200, Zhongbei Rd., Zhongli District, 320 Taoyuan, Taiwan, Republic of China, Email: [email protected]

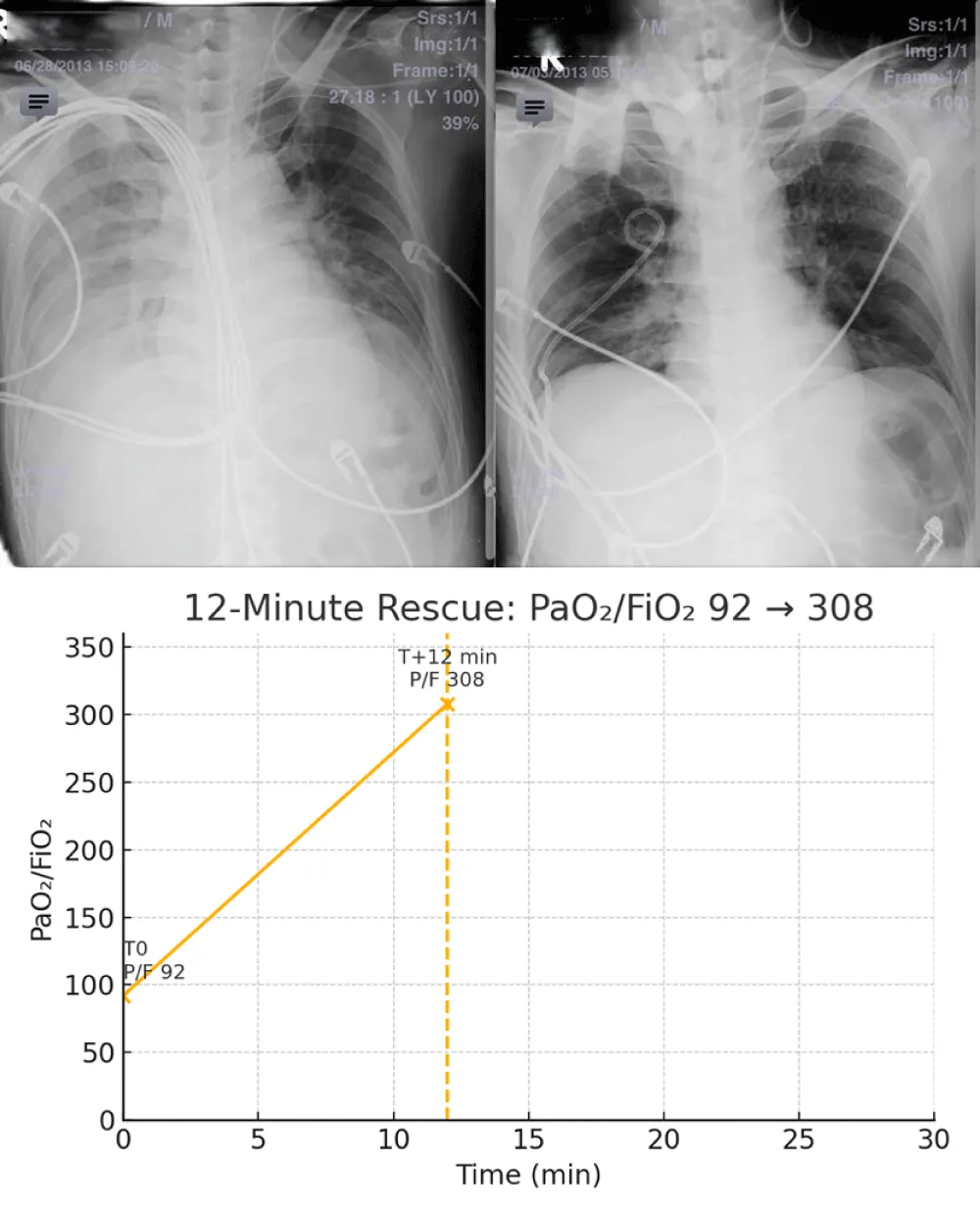

At presentation, the PaO2/FiO2 ratio was 92 with SpO2 82% on high‑flow nasal cannula 15 L/min at FiO2 0.80. Ultrasound‑guided 14‑Fr pigtail decompression (right 5th intercostal space, anterior axillary line) at T0 evacuated ~220 mL air with scant blood‑tinged fluid; oxygenation improved to a PaO2/FiO2 of 308 within 12 minutes (PaO2/FiO2 308 on 3 L nasal cannula; A–a gradient 528 → 112 mmHg), and induction proceeded at T+30 minutes with ORIF commencing at T+90 minutes the same day.

Background: Hypoxemia before fracture fixation in polytrauma often derives from reversible thoracic causes. We report a case in which unilateral radiographic lung decompensation with low oxygen saturation was rapidly reversed by targeted pigtail decompression, enabling safe anesthesia and definitive fixation.

Case: A patient with bilateral open distal femur fractures (right Gustilo‑Anderson II, left I) developed acute hypoxemia with unilateral alveolar opacity on chest radiography. Ultrasound‑guided 14‑Fr pigtail decompression immediately improved oxygenation and radiographic aeration, allowing timely ORIF.

Outcome: Postoperative recovery was uneventful; long‑leg follow‑up radiographs confirmed bony healing.

Interpretation: When low SpO2 coexists with a unilateral pattern, clinicians should not be constrained by the prior of bilateral pulmonary edema. Rapid, targeted pleural decompression (pigtail) can eliminate a reversible pleural barrier within minutes and open an anesthetic window for fracture fixation. Mechanistically, hyperacute decompensation may reflect a convergence of pleural tension‑related shunt, re‑expansion lung injury, negative‑pressure/airway factors, and fat‑embolism‑related pulmonary vascular responses.

Design: Case report with focused literature review.

In multiply injured patients, definitive fixation hinges on cardiopulmonary stability. Edema patterns are classically bilateral in hydrostatic or permeability‑driven injury; however, unilateral radiographic decompensation can occur in early re‑expansion pulmonary edema (REPE), negative‑pressure pulmonary edema (NPPE), airway malposition, and regional perfusion/ventilation imbalance. At the bedside, prompt exclusion of tension physiology and directed decompression takes priority because the benefit may be immediate and decisive for definitive orthopedic care [1].

Taken together, these changes constitute a 12‑minute rescue, with PaO₂/FiO₂ rising from 92 to 308 and hemodynamics stabilizing, thereby enabling same‑day ORIF.

A middle‑aged patient sustained bilateral open distal femur fractures in a high‑energy mechanism (right Gustilo‑Anderson type II; left type I). During pre‑operative resuscitation, the patient developed acute hypoxemia with a unilateral alveolar opacity on the right‑sided lung field. Point‑of‑care lung ultrasound and radiography favored a pleural‑compartment problem over diffuse edema. An ultrasound‑guided 14‑Fr pigtail catheter was placed for targeted decompression. SpO₂ rose promptly and a control radiograph showed re‑expansion. After stabilization, staged definitive fixation (open reduction and internal fixation) was performed. Recovery was uneventful; subsequent long‑leg alignment films demonstrated consolidating callus and functionally symmetric lower limbs.

Revision (Hemodynamics from imaging): Relief of pathologically elevated pleural pressure would be expected to reduce right‑atrial/juxtapericardial pressure, increase venous return, and promptly improve cardiac output; immediate radiographic correlates can include reversal of mediastinal shift and a lower apparent cardiothoracic ratio. Intubation and controlled ventilation improve inspiratory frame and lung inflation, further reducing the apparent silhouette; however, because AP portable cardiothoracic measurements are technique‑sensitive, we interpret these imaging changes as physiologically coherent but not proof of hemodynamic change.

Revision (discussion – evidence vs. speculation): The causal chain remains inferential. Our evidence‑based observations comprise the unilateral radiographic pattern, immediate improvement after pleural decompression, and restoration of gas exchange; by contrast, the contributions of REPE, NPPE, and fat‑embolism physiology are mechanistic hypotheses without direct confirmatory testing in this case. We therefore present these mechanisms as plausible, not proven, in accordance with contemporary reviews [2-11].

Scope of inference: Our evidence‑based elements include unilateral imaging, ultrasound evidence of pleural‑compartment tension, immediate physiologic normalization after decompression, and a durable anesthetic window enabling same‑day ORIF. Mechanistic contributors from NPPE/REPE and marrow‑fat physiology remain plausible rather than proven in this single case; we therefore present them as modifiers rather than primary causes [2-6,12,13].

Two pathophysiological axes plausibly converged in this case. First, pleural‑compartment tension—air or fluid—can create a large shunt fraction by collapsing alveoli and redirecting perfusion to the dependent lung, a process that can appear unilateral on imaging; relief by small‑bore catheter is effective and supported by randomized trials and meta‑analyses in traumatic thoracic pathology [14-16]. Second, hyperacute edema in a unilateral distribution can follow sudden re‑expansion (REPE) where mechanical stress and increased capillary permeability flood the ipsilateral lung; modern case series and reviews emphasize its rarity but potential severity [2,3]. NPPE—classically bilateral—can rarely be unilateral when obstruction or malposition is regional; case reports document dependent‑lung‑predominant edema or endobronchial intubation–related unilateral patterns [4-6]. Finally, long‑bone injury can release marrow fat and free fatty acids; experimental models demonstrate acute rises in mean pulmonary arterial pressure, ventilation‑perfusion mismatch, and inflammatory endothelial injury, any of which intensify an already precarious gas‑exchange state [7-11]. These mechanisms are not mutually exclusive: transient fat‑embolism‑related pulmonary vasoconstriction may increase microvascular hydrostatic stress, while rapid lung re‑expansion adds capillary ‘stress failure’—together producing a hyperacute, side‑predominant picture that is reversible once pleural mechanics are normalized.

With oxygenation restored, fixation followed an Early Appropriate Care (EAC) paradigm—proceeding to definitive management once lactate, pH, and base‑excess criteria indicate adequate resuscitation—to minimize pulmonary and systemic complications in polytrauma [17,18]. This case underscores that cardiopulmonary rescue is a prerequisite to ‘timing’ decisions; a short, targeted decompression can convert a high‑risk physiology into an anesthetic window for safe ORIF.

Conclusion

In polytrauma, the precondition for fracture fixation is cardiopulmonary stability. When unilateral findings accompany hypoxemia, clinicians should resist anchoring bias to the prior. Rapid, ultrasound‑guided pigtail decompression can resolve a reversible pleural barrier within minutes and open a safe window for anesthesia and fixation.

Methods (practical bedside protocol)

Practical implications — Lessons learned: Protocol anchors and rationale. We anchor the bedside flow in LUS‑first triage for tension physiology [19,20]; controlled pleural off‑loading with initial water‑seal/one‑way valve to mitigate REPE [21,22]; and EAC‑aligned timing once gas‑exchange and perfusion markers normalize [17,18,23]. When a hyperacute unilateral pattern is present, a small‑bore catheter can be both diagnostic and therapeutic, rapidly restoring oxygenation without delaying orthopedics [14-16,24].

Pragmatic documentation: when feasible, record pre/post cardiothoracic ratio (CTR) on the portable CXR and a synchronized vital‑sign snapshot (HR, BP, SpO₂, ventilator settings) to anchor the physiologic turnaround in the chart.

In multiply-injured patients with hyperacute unilateral decompensation, a brief, ultrasound‑guided pleural decompression can convert a high‑risk physiology into a safe anesthetic window. Key bedside points are to (i) prioritize exclusion of tension physiology by lung/pleural ultrasound, (ii) employ controlled pigtail decompression with avoidance of early high‑suction to reduce REPE risk, and (iii) re‑evaluate oxygenation within 15–30 minutes; if normalized, proceed with definitive fixation under Early Appropriate Care thresholds [17,18] (Figures 1-4).

Figure 1: A–D: Hyperacute unilateral decompensation, 12‑minute rescue, and orthopedic context. A: pre‑intervention chest radiograph with right‑lung opacification/volume loss. B: post‑decompression ~T+12 min (endotracheal tube in situ) with re‑expansion and improved aeration. C: oxygenation trajectory (0–30 min) showing PaO₂/FiO₂ 92→308 within 12 minutes; induction at T+30 min and ORIF at T+90 min. D: representative pre‑operative distal femur views demonstrating bilateral, comminuted metaphyseal–diaphyseal extension. Bedside LUS guided targeted decompression with initial water‑seal to limit early suction and REPE risk [19-22]; small‑bore use aligns with trauma literature [14-16,24]; timing followed EAC once physiology normalized [17,18,23]; the distal femur patterns provide a plausible V/Q amplifier consistent with FES imaging reviews [13].

Figure 2: Pre-operative imaging of distal femur fractures. Representative lateral views demonstrate bilateral open distal femur fractures (right Gustilo‑Anderson II; left I).

Figure 3: Additional pre-operative oblique/lateral projections detailing comminution and distal extension.

Figure 4: Long-leg standing follow-up radiograph confirming alignment and interval bony consolidation after staged ORIF.

1) Screen physiology: bedside lung/pleural ultrasound; rule out tension; arterial blood gas.

2) Prepare: local anesthesia, sterile field; select 14-Fr pigtail; lateral/anterior axillary line at safe triangle; ultrasound to target pleural air/fluid pocket.

3) Controlled decompression: Seldinger technique; connect to one‑way valve/water seal; avoid excessive negative suction at onset to reduce REPE risk.

4) Reassess: pulse oximetry and capnography; repeat CXR within 15-30 minutes; if oxygenation normalizes and radiograph improves, proceed to anesthesia and fixation per EAC criteria.

5) Document and monitor for REPE/NPPE signs during the first 1–2 hours.

Ethics and consent

The case was managed according to institutional trauma protocols. Identifiers have been removed from images; written consent for publication was obtained.

At outpatient follow-up, the patient ambulated independently without exertional dyspnea. On examination, the bilateral knee range of motion measured 2°–110° with no extensor lag. Radiographs demonstrated progressive callus with maintained alignment; no readmissions or supplemental oxygen were required.

- Chiu HY, Ho YC, Yang PC, Chiang CM, Chung CC, Wu WC, et al. Targeted pigtail decompression for pneumothorax/hemothorax in trauma: experience and outcomes. Recommendation for management of patients with their first episode of primary spontaneous pneumothorax, using video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery or conservative treatment. Sci Rep. 2021;11:10874. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-90113-w

- Mahfood S, Hix WR, Aaron BL, Blaes P, Watson DC. Reexpansion pulmonary edema. Ann Thorac Surg. 1988;45(3):340–345. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0003-4975(10)62480-0

- Cusumano G, La Via L, Terminella A, Sorbello M. Re-expansion pulmonary edema as a life-threatening complication in massive, long-standing pneumothorax: case series and literature review. J Clin Med. 2024;13(9):2667. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13092667

- Vandse R, Chandra S, D'Souza N, Rao G, Mathur PP. Negative pressure pulmonary edema with laryngeal mask airway. Int J Crit Illn Inj Sci. 2012;2(2):101–103. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.14426

- Goodman BT, Richardson MG. Unilateral negative pressure pulmonary edema—a complication of endobronchial intubation. Can J Anaesth. 2008;55(10):691–695. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf03017745

- Sullivan M, Kolb JC. Unilateral negative pressure pulmonary edema during anesthesia. Can J Anaesth. 1999;46(9):1053–1056. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/BF03013201

- Parker FB Jr, Wax SD, Kusajima K, Webb WR. Hemodynamic and pathological findings in experimental fat embolism. Arch Surg. 1974;108(1):70–74. https://doi.org/10.1001/archsurg.1974.01350250060017

- Zhou F, Zhang Z, Song B, Peng Z, Zhang G, Wang Y. Pulmonary fat embolism and related effects during femoral intramedullary procedures: an experimental animal study. Exp Ther Med. 2013;6(5):1177–1183. https://doi.org/10.3892/etm.2013.1143

- Kwiatt ME, Seamon MJ. Fat embolism syndrome. Int J Crit Illn Inj Sci. 2013;3(1):64–68. https://doi.org/10.4103/2229-5151.109426

- Newbigin K, Souza CA, Armstrong M, Marchiori E, Gupta A, Inacio J, et al. Fat embolism syndrome: state-of-the-art review focused on pulmonary imaging findings. Respir Med. 2016;113:93–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2016.01.018

- Bousseau S, Chatterjee S, Humbert M. Pathophysiology and new advances in pulmonary hypertension. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2023;10:1130556. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjmed-2022-000137

- Ma J, Liu T, Wang Q, Xia X, Guo Z, Feng Q, et al. Negative pressure pulmonary edema (Review). Exp Ther Med. 2023;26(3):455. https://doi.org/10.3892/etm.2023.12154

- Qi M, Zhou H, Yi Q, Wang M, Tang Y. Pulmonary CT imaging findings in fat embolism syndrome. Insights Imaging. 2024;15:84. https://doi.org/10.7861/clinmed.2022-0428

- Kulvatunyou N, Erickson L, Vijayasekaran A, Gries L, Joseph B, Friese RF, et al. Randomized clinical trial of pigtail catheter versus chest tube in injured patients with uncomplicated traumatic pneumothorax. Br J Surg. 2014;101(2):17–22. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.9377

- Chang SH, Kang YN, Chiu HY. A systematic review and meta-analysis comparing the pigtail catheter and chest tube as the initial treatment for pneumothorax. Chest. 2018;153(5):1201–1212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2018.01.048

- Joseph B, Karmy-Jones R, Breeding T, Andrade R, Zagales R, Khan A, et al. Outcomes of pigtail catheter placement versus chest tube in thoracic trauma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am Surg. 2023;89(9):1978–1989. https://doi.org/10.1177/00031348231157809

- Vallier HA, Wang X, Moore TA, Wilczewski PA, Steinmetz MP, Wagner KG, et al. Complications are reduced with a protocol to standardize the timing of fixation based on the response to resuscitation. J Orthop Trauma. 2015;29(1):1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-015-0298-1

- Pape HC, Giannoudis PV, Krettek C, Velmahos GD, Buckley R, Giannoudis PV. Timing of major fracture care in polytrauma patients—an update on Early Appropriate Care. Int Orthop. 2019;43(7):1789–1795. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.injury.2019.09.021

- Beshara M, Bittner EA, Goffi A, Berra L, Chang MG. Nuts and bolts of lung ultrasound: utility, scanning techniques, protocols, and findings in common pathologies. Crit Care. 2024;28:328. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-024-05102-y

- Demi L, Wolfram F, Klersy C, De Silvestri A, Ferretti VV, Muller M, et al. New International Guidelines and Consensus on the Use of Lung Ultrasound. J Ultrasound Med. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1002/jum.16088

- Asciak R, Bedawi EO, Bhatnagar R, Clive AO, Hassan M, Lloyd H, et al. British Thoracic Society. Clinical Statement on Pleural Procedures. Thorax. 2023 (update). https://doi.org/10.1136/thorax-2022-219371

- Subedi A, Banjade P, Joshi S, Sharma M, Surani S. British Thoracic Society. Pleural Procedures – Online Appendix 10: Chest drain devices & suction (guidance on avoiding early high suction to reduce REPE risk). 2023. https://doi.org/10.2174/0118743064286775231128104253

- Pfeifer R, Klingebiel FK, Balogh ZJ, Beeres FJP, Coimbra R, Fang C, et al. Early major fracture care in polytrauma—priorities in the debate; what to do. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1097/ta.0000000000004428

- Le KDR, Wang AJ, Sadik K, Fink K, Haycock S, et al. Pigtail Catheter Compared to Formal Intercostal Catheter for the Management of Isolated Traumatic Pneumothorax: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Complications. 2024;1(3):68–78. https://doi.org/10.3390/complications1030011